Freedom’s ferment

IT HAD no long and storied history, few highly educated clergy, no bishops except over local congregations, and no carefully organized evangelistic campaigns. Yet this upstart Christian phenomenon swept into its fold thousands upon thousands of Americans in the early nineteenth century, even as it rejected all traditional churches—Catholic and Protestant alike—and aspired to become the universal church that would unify all Christians and inaugurate the millennial dawn. Perhaps no Christian tradition more fully mirrored the democratic and optimistic world of the new American republic.

A democratic mood

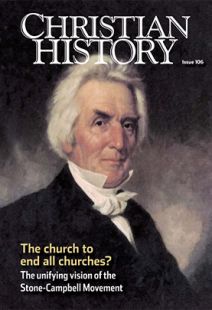

Seeking to follow biblical directives, Alexander Campbell and Barton W. Stone—along with the thousands who looked to them for guidance—passionately devoted themselves to democracy and freedom in the context of the Christian religion. As it turned out, this emphasis held great appeal for Americans newly launched on their experiment of self-government.

Stone and Campbell rejected creeds, claiming to follow no text but the Bible. They extolled the ability of ordinary people to read the Bible and understand it for themselves. And they understood their work as reflecting the passion for freedom they saw all around them.

“The present conflict between the Bible and party creeds and confessions,” one member of their movement wrote, “is perfectly analogous to the revolutionary war between Britain and America; liberty was contended for on one side, and dominion and power on the other.”

Another author thought the Jeffersonian phrase from the Declaration of Independence regarding humanity’s “unalienable rights” applied equally to “free investigation” and “sober and diligent inquiry after [religious] truth.” Likewise, Stone and Campbell rejected any ecclesial authority—whether bishop or synod or priest—that supplanted the authority of the local church. That emphasis renders some parts of the tradition radically independent to this day, answering to no authority except the will of the people who compose a given congregation and the elders that congregation appoints.

Restoring pure beginnings

But freedom was not all that motivated Stone and Campbell. They were deeply committed to recovering the primitive church of the New Testament—the golden age, they thought, of the Christian religion. The term they used to describe that endeavor was “restoration.” Campbell in fact often spoke of “the restoration of the ancient order of things” as one of the goals he was trying to reach as a Christian leader.

America’s founders, too, were seeking purity—in their case in nature. They thought that God had built timeless principles of freedom into nature at the time of creation, and they wanted to dig them back out from under the obscuring centuries of kingcraft, tyranny, and corruption. This is what Jefferson meant when, in the Declaration of Independence, he appealed to “self-evident truths” that “Nature’s God” had established.

Jefferson’s friend, Thomas Paine, also proclaimed that the American government was like “the beginning of a world.” Viewing the American system, he wrote, “We are brought at once to the point of seeing government begin, as if we had lived in the beginning of time.”

Reading and hearing such arguments, many Christians asked themselves an obvious question: if the founders had restored the God-intended form of secular government, could Christians do any less with the church?

If America’s founders could reject kings and tyrants and build the American nation on democratic principles inspired by God, so Alexander Campbell, Barton Stone, and thousands of other Christians would reject priests, bishops, and popes, and restore similar democratic principles that they believed had been central to the primitive church.

The golden age of peace

Americans in the early nineteenth century sought to build their nation on principles—democracy and freedom—that they considered to be as old as the beginning of time. A nation built on those ancient ideals, they argued, would finally usher in the long-anticipated millennium.

The millennium would be started on earth by human beings in obedience to God’s will for creation, and it would be a golden age of peace and freedom for all humankind. No one made this point more clearly than popular American preacher Lyman Beecher.

He explained to Americans that the light their new country would send into the world “will throw its beams beyond the waves; it will shine into darkness there and be comprehended; it will awaken desire and hope and effort, and produce revolutions and overturnings, until the world is free.”

And when people around the world were free, he proclaimed, “the trumpet of Jubilee [will] sound, and earth’s debased millions will leap from the dust, and shake off their chains, and cry, ‘Hosanna to the Son of David.’”

Water under the bridge

Christians in the Stone-Campbell Movement picked up on this same vision of the coming dawn. But if the larger public applied that vision to the nation, the Stone-Campbell Movement applied it to the church. Alexander Campbell wrote in 1825 that “just in so far as the ancient order of things, or the religion of the New Testament, is restored, just so far has the Millennium commenced.”

But whether applied to the nation or the church, the logic of this vision was clear: restoration of the purity of the first golden age would usher in the purity of the final golden age. In that way, all human history essentially became water under the bridge. American citizens, on the one hand, and Stone-Campbell Christians, on the other, were crossing that bridge from one golden age to the other.

Such a view was written into nothing less than the Great Seal of the United States. Americans commonly think of the seal’s front, if they think of it at all—an eagle with arrows and olive branches. But on the back side of the seal is an unfinished pyramid with the date of the American founding—1776—on its base.

The pyramid grows from an arid and barren landscape, suggesting that all human history, when compared to this new nation, is barren—and therefore fundamentally irrelevant. Below the pyramid appear the Latin words novus ordo seclorum, “a new order of the ages.” The United States was not simply a new nation when compared to other nations. It was radically new since it was also radically old, building on the ancient foundations of freedom laid in the Garden of Eden.

The pyramid is unfinished because the American example was yet to spread around the globe: though the dawn was rising, the final golden day was yet to come. Above the unfinished pyramid, the eye of God looks on with approval, and above that eye a Latin motto affirms: “He has smiled on our beginnings.”

The Stone-Campbell Movement embraced this very same rejection of history. The difference was that while the nation rejected secular history, the Stone-Campbell Movement rejected all Christian history since the days of the primitive church.

Two of Barton Stone’s associates in Kentucky, for example, wrote that “we are not personally acquainted with the writings of John Calvin, nor are we certain how nearly we agree with his views of divine truth; neither do we care.”

Unity out of diversity

Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone also mirrored the nation in the plan they devised for the unity of all Christians. Theirs was a vision of unity in diversity with long roots that stretched all the way back to Paul’s metaphor of the church as the body of Christ and Jesus’ unity prayer (John 17). But they also borrowed that vision from key Enlightenment thinkers—the very same thinkers who inspired America’s founders.

One of those thinkers was Lord Herbert of Cherbury, the father of the English Enlightenment. Distressed by the bloody religious wars that plagued Europe in the seventeenth century, he published a book that he called De Veritate (1624), or “The Truth.”

In that book, he proposed a way to end religious warfare. While Herbert valued the Bible highly as a “source of consolation and support,” he also knew that it is a complex book, full of hundreds of teachings that Christians could interpret in many ways and then bind those interpretations on others.

Herbert therefore proposed that reasonable people banish from the public square all points of doctrine peculiar to particular religions or holy texts. Instead, he argued that citizens should build the public square on two great truths that everyone could know through the light of nature—that God exists and that a moral order pervades the universe.

These two truths, Herbert believed, are the essential truths that stand at the heart of every great religion. They could thus serve as the basis for religious unity.

We hold these truths . . .

When the founders created the American nation, they, too, understood religion’s potential to inspire civic strife and even religious warfare. Such religion could destroy the American nation before it had a chance to succeed. So they addressed that problem in the same way Herbert had, not seeking to build the nation on this or that interpretation of the Bible or on any peculiar doctrine.

Instead they appealed to “self-evident truths” accessible to all humans through the light of nature. Those “self-evident truths” were that “all men are created equal” and “endowed with certain unalienable rights”—rights that could not be taken away since God had woven them into the fabric of nature itself.

Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone commended that same formula to Christians in the early nineteenth century. The difference between the founders and the Stone-Campbell Movement was that the founders uncovered essential truths in nature while Stone and Campbell found their essential truths in the biblical text.

They sought core essentials that formed the bedrock of the ancient church established by Jesus and the apostles. And making famous a phrase first used by Lutheran ecumenist Rupertus Meldenius (1582–1651), they appealed: “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; in all things, charity.”

Dissenting against dissent

The American world of the early nineteenth century was committed to dissent against everything from corrupt and oppressive regimes to traditional social structures. Ironically, the Stone-Campbell Movement so faithfully mirrored the values of the new nation, including the value of dissent, that it ultimately dissented against America itself.

Alexander Campbell argued that the kingdom of God would finally triumph over all human governments, “the very best as well as the very worst,” including the government of the United States.

“The admirers of American liberty and American institutions have no cause to regret such an event, nor cause to fear it,” he wrote. “It will be but the removing of a tent to build a temple—the falling of a cottage after the family are [sic] removed into a castle.”

Barton Stone and his disciples expressed this dissent in especially provocative ways—arguing that Jesus might be the one bringing the millennial dawn. Stone wrote that “the lawful King, Jesus Christ, will shortly put them [human governments] all down, and reign with his Saints on earth a thousand years, without a rival.” Christians must therefore “cease to support any other government on earth by our counsels, cooperation, and choice.” Stone and his followers thus refused to vote, refused to hold political office, and refused to serve in the US military.

Even while showing themselves children of their era in so many ways, Stone-Campbell Movement Christians pledged their ultimate allegiance not to the nation but to the kingdom of God. CH

By Richard Hughes

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #106 in 2013]

Richard Hughes is distinguished professor of religion at Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania.Next articles

No name but the name of Christ

The beginnings of the Stone-Campbell movement

D. Newell Williams and Douglas A. FosterWho was that white-robed man?

Joseph Thomas, “the White Pilgrim,” tried to be as apostolic as possible

Richard HughesHow to speak Stone-Campbell

What do they mean when they say . . . ?

Douglas A. Foster and McGarvey IceReading the Bible to enjoy the God of the Bible

Connecting the life of the mind to the world of revivalism

Richard HughesSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate