No name but the name of Christ

ONE FOUNDER was upset at fellow clergy who condemned Presbyterians and Methodists for—gasp!—dating after being introduced at revival meetings. Two others were sick of religious divisions in their homeland and of being marooned in a church so sectarian it was called the Associate Synod of Ulster of the Anti-Burgher Seceders. Little did they know they were founding a movement themselves. They just wanted peace and Christian unity.

Marrying meetings?

By 1800, the awakening known as the Great Western Revival had begun in Tennessee and Kentucky (both were the “West” in 1800). Presbyterians and Methodists began coming together in revivals lasting four to six days and culminating in “union meetings,” where they joined in celebrating the Lord’s Supper. The meetings drew thousands and included both blacks and whites—which convinced many whites to free their slaves.

The gatherings also became famous for the “falling exercise.” Powerfully affected by sermons and testimonies, people fell to the ground and appeared dead for hours. Then they arose praising Jesus and calling others to him for salvation.

Not all Presbyterians supported the revivals. Their biggest objections were not to the falling exercise or the freeing of slaves, but that young adults from Methodist and Presbyterian families were meeting at these heated gatherings and marrying. In many cases, the newlyweds were joining the Methodist Church!

Some Presbyterian ministers began urging their colleagues to “preach up” the differences between Methodist and Presbyterian doctrine, specifically the Presbyterian teaching derived from Calvin’s doctrine of predestination: the idea that God had chosen particular human beings to be damned and others to be saved before the foundation of the earth.

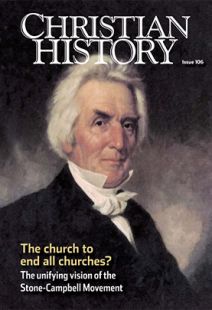

Barton Warren Stone (1772–1844) was a Presbyterian preacher born in Maryland, raised on the Virginia frontier, and educated in a church academy in North Carolina. He and other Presbyterian revival leaders refused to preach predestination. They knew it would offend the Methodists and bring the “union meetings” to an end.

They had also personally, though quietly, rejected it as inconsistent with God’s love revealed in Jesus. As a result, Presbyterian defenders of the doctrine tried to remove Stone and his friends from the ministry.

Stone and four other ministers withdrew from their jurisdiction and formed their own Springfield Presbytery. But they did not stop there. In June 1804, they published a tract titled “The Last Will and Testament of Springfield Presbytery” rejecting denominations and creedal statements as divisive.

They wrote: “We will, that this body die, be dissolved, and sink into union with the Body of Christ at large; for there is but one body, and one Spirit, even as we are called in one hope of our calling . . . that our power of making laws for the government of the church, and executing them by delegated authority, forever cease; that the people may have free course to the Bible, and adopt the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus.”

Taking the generic name “Christians,” they sought to further the unity they had experienced in the revivals and convince Presbyterians and Methodists to unite. They failed but did gain supporters among Baptists in Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, and Indiana.

The Campbells are coming

Meanwhile, Thomas (1763–1854) and Alexander Campbell (1788–1866), father and son, were also seeking an end to division. They came from Ireland, where they had been Presbyterians (Church of Scotland). Their particular sect had splintered over Scottish political and religious matters irrelevant in Ireland. Still, the differences kept the factions from fellowship.

Also, the British rulers (Anglican) never fully trusted Presbyterian loyalty, and there was friction between Protestants and Catholics. In the midst of this religious strife, the Campbells longed for peace and Christian unity.

After several unsuccessful attempts to bring Presbyterians in Northern Ireland together, Thomas Campbell became seriously ill. On his doctor’s advice, he sailed to America in 1809. While conducting worship for Seceder Presbyterians near Pittsburgh, he served the Lord’s Supper to some worshipers outside the group who had shown up to hear the distinguished guest preacher.

For this, his presbytery attempted to defrock him. Though his conviction was overturned, he soon separated from the Presbyterians and formed a group called the Christian Association.

Campbell wrote the new group’s purpose statement—the Declaration and Address of the Christian Association of Washington. He claimed all Christians “should consider each other as the precious saints of God . . . bought with the same price, and joint heirs of the same inheritance. Whom God hath thus joined together no man should dare to put asunder.”

Not many responded. Instead, the Christian Association became a local church, taking the name “disciples of Christ.” Like Stone’s “Christians” the name was intended to be simple and nondivisive. When Thomas’s family joined him, his son Alexander embraced the ideals of the Declaration and Address.

When, in 1812, Alexander’s wife had a baby, the child’s birth forced him to rethink infant baptism as taught by the Presbyterians. He concluded that the New Testament taught baptism of believers by immersion. That June, Alexander, Thomas, and five others from the Christian Association were immersed.

Some assumed Campbell denied that those baptized as infants were Christians. Yet Campbell never said so. He stated in 1837 that he “could not make any one duty the standard of Christian state or character, not even immersion into the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

The Campbells worked for reform as part of Baptist churches for over 15 years. In his first journal, Christian Baptist (1823–1830), Alexander published a series of articles titled “A Restoration of the Ancient Order of Things” detailing what he saw as beliefs and practices of the apostolic churches in the early Christian centuries: believers’ baptism by immersion, weekly Lord’s Supper, congregational self-rule, and “simple” worship with unaccompanied congregational singing and no formal liturgy.

In 1827 the Mahoning Baptist Association, a group supporting Campbell’s views, asked Walter Scott (1796–1861) to serve as a traveling evangelist. Scott taught that one could accept the gospel, turn from sin, and in faith be baptized without needing to pass through tearful struggles and an emotional conversion experience to show acceptance of the Holy Spirit.

This view would remain profoundly influential and the basis of the popular “five-finger exercise” for teaching the way of salvation (see “A story all their own,” pp. 38–40).

Over the next three years, Scott baptized about 3,000 people. But soon Baptists and Campbell reformers began to separate over the purpose of baptism and the need for organization beyond the local congregation. Who else could Campbell cooperate with in the cause of Christian unity?

Let’s get together

Enter Barton Stone. Campbell and Stone shared a commitment to the visible unity of Christians based on the teachings of Scripture. But they had big differences, too.

Stone saw Jesus as Savior, but not equal to God; Campbell held a traditional view of the Trinity. Stone’s group practiced immersion but did not make it a requirement for joining; Campbell insisted on immersion for membership. Stone used the name “Christian,” while Campbell preferred “disciples of Christ.” Stone did not believe that Christ died to “pay for” our sins, but to demonstrate God’s absolute love.

But both were committed to Christ’s prayer in John 17 that all might be one so the world would believe. And both had glimpsed union when Christians came together to work and worship despite differences.

In late 1831, Stone and John Smith, a leader from the Campbell movement, called meetings of church leaders in Georgetown and Lexington, Kentucky. In both places, the congregations united. There was no central organization; in each town the churches simply decided to unite.

On the first Sunday of 1832, the two Lexington groups shared communion together as one fellowship. The Kentucky churches sent messengers to tell what had happened and urge other churches to do the same—which they did, over and over. By 1860 the Stone-Campbell Movement was one of the 10 largest Christian groups in the United States, numbering about 200,000—all while trying to be nothing but Christians working together in unity, bearing no name but the name of Christ. CH

By D. Newell Williams and Douglas A. Foster

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #106 in 2013]

Douglas A. Foster is professor of church history and directs the Center for Restoration Studies at Abilene Christian University. D. Newell Williams is president and professor of church history at Brite Divinity School, Texas Christian University. Parts of this article are adapted from The Story of Churches of Christ by Douglas A. Foster (ACU Press, 2013) and are used by permission.Next articles

Who was that white-robed man?

Joseph Thomas, “the White Pilgrim,” tried to be as apostolic as possible

Richard HughesHow to speak Stone-Campbell

What do they mean when they say . . . ?

Douglas A. Foster and McGarvey IceReading the Bible to enjoy the God of the Bible

Connecting the life of the mind to the world of revivalism

Richard HughesNorth and South

Was the division in the “unity movement” as much about geography as theology?

Richard HughesSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate