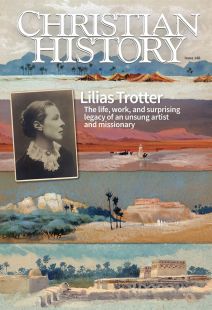

Editor's note: Lilias Trotter

Let me talk to you about desultory bees.

“Desultory,” if you are wondering, means moving from one thing to another in a haphazard fashion. And the desultory wandering of bees is on my mind because of the subject of this issue: Victorian artist and missionary Isabella Lilias Trotter. Lilias—she always went by her middle name—is probably unknown to most of you. She was unknown to me until, a few years ago, I received a beautiful package in the mail from Lilias Trotter Legacy (LTL) with republished facsimiles of several of her sketchbooks and devotional books.

They looked lovely, but I get a lot of books in the mail, and I set them aside until our director of editorial staff, Kaylena Radcliff, mentioned that she was in conversation with LTL about doing an issue on Trotter. When I got the books out again, I almost fell out of my chair. The tiny, delicate artwork, thoughtfully done and vibrantly colored, pulled me immediately into scenes I had never considered before—roadside flowers, snow-capped mountains, markets, courtyards in Algiers. I don’t know that I had ever looked at flowers so closely before. The images were paired with intense, mystical prose, grounded in the same close observation of nature that had produced the amazing flowers.

I would later discover that my reaction almost exactly paralleled that of famed nineteenth-century art critic John Ruskin when he was introduced to Trotter’s art, which he called “right minded” and “careful.” As you will soon learn, he told her that his instruction and patronage could place her among England’s greatest living artists—if she was willing to stop helping people (she was doing charity work with the YWCA) and focus solely on creating art.

Trotter turned Ruskin down. She continued to paint, she continued to serve, and she eventually went to Algiers as a missionary—not with an organization, but on her own. She went here and there, in England and Algiers, serving and painting, like a bee pollinating flowers. She managed, in the course of her life and work, to meet, influence, and be influenced by many famous people, and to leave a legacy you may not even realize belongs to her, from many modern missionary methods to the song “Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus.” But she did not follow any expected path.

“A bee comforted me very much this morning concerning the desultoriness that troubles me in our work. There seems so infinitely much to be done, that nothing gets done thoroughly. If work were more concentrated, as it must be in educational or medical missions, there would be less of this—but we seem only to touch souls and leave them. And that was what the bee was doing, figuratively speaking. He was hovering among some blackberry sprays, just touching the flowers here and there in a very tentative way, yet all unconsciously, life-life-life was left behind at every touch, as the miracle-working pollen grains were transferred to the place where they could set the unseen spring working. We have only to see to it that we are surcharged, like the bees, with potential life. It is God and His eternity that will do the work. Yet He needs His wandering desultory bees.”—Lilias Trotter, diary entry, July 9, 1907

She did not become the greatest artist in England, nor did she write classic children’s fantasy like her literary mentor George MacDonald or lead worldwide conferences like her missions mentor John R. Mott or get called an apostle like her colleague Samuel Zwemer or have her life turned into children’s stories like her pen pal Amy Carmichael.

Maybe when you were young you were told you had talent and promise and could be the greatest at something, if you only tried. Maybe you were told what you needed in life was single-minded focus. Maybe an expected career path was laid out for you—outside the church or inside it. Maybe you were told the only way to get where you needed to go to bring Jesus to the world involved the approval of secular cultural gatekeepers or the acclaim of illustrious Christian organizations.

Maybe, instead, you went here and there like a bee; trying first one thing, and then another, always unsure of the next step or even where you were going, but looking for God wherever you happened to end up.

Maybe everyone who talked to you was wrong. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, Managing editorNext articles

A key in the Master’s hand

An unsung artist and missionary whose story unlocks many doors

Miriam Huffman RocknessLearning to see

John Ruskin loomed large over an art world and a culture wrestling with both truth and beauty

Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson & Jennifer TraftonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate