Remaking the world

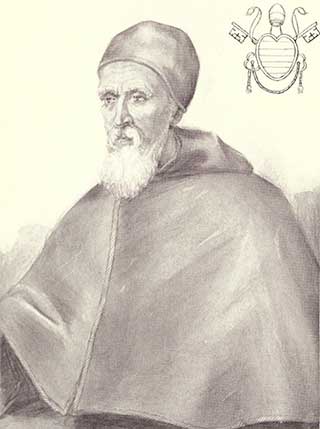

Gian Pietro Carafa (1476–1559)

[Pope Paul IV; Wikipedia]

OF THE MAN who became Pope Paul IV, a later writer said, “How so austere a person could be chosen pope was a mystery to everyone, especially to himself.” A member of a wealthy Neapolitan noble family, his uncle, cardinal and diplomat Oliviero Carafa (1430–1511), mentored him from a young age. Gian Pietro tried to join the Dominicans as a teenager, but his family objected. However he soon became a priest and was introduced into the papal court.

When Gian Pietro was about 30, Oliviero resigned the bishopric of Chieti (Theate) to allow his nephew to assume the title. The younger Carafa also served as papal ambassador to England and Spain, but in 1524 he resigned all his titles and benefices to help found a new religious order, the Theatines, which hoped to call both clergy and laity to a more virtuous and moral life. With a focus on founding oratories (chapels) and hospitals, the Theatines appointed Carafa as their first general.

In 1534 the newly consecrated Pope Paul III placed Carafa and other reform-minded clergy such as Gasparo Contarini and Reginald Pole on a commission charged with reforming the papal court (see “The road not taken,” pp. 15–18). The commission’s report, though never put into effect, did influence later changes. In 1542 Paul III reconstituted the Roman Inquisition and made Carafa (now a cardinal) inquisitor general.

After the 22-day pontificate of Marcellus II in early 1555, it surprised everyone when the 80-year-old Cardinal Carafa was elected pope as Paul IV. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who knew of Carafa’s anti-Spanish prejudices, tried to veto the election, but failed.

Carafa’s desires for reform were by all accounts sincere, but his unbending attitude toward Protestants and others and his inability to practice diplomacy created many enemies. He denounced the Peace of Augsburg between Lutherans and Catholics as heresy; attacked Pole because he disagreed with Pole’s handling of England’s return to Catholicism; refused to reassemble the suspended Council of Trent; encouraged the Inquisition; promoted his young nephews (he made one a cardinal) despite their scandalous behavior; introduced the Index of Prohibited Books (which banned all Protestant books as well as translations of the Bible into Italian or German); made an alliance with France which renewed war between France and Spain; and forced Jews in Rome to live in a ghetto.

When he died in 1559, crowds rioted in Rome, pulled down his statue, and chanted the following poem: “Carafa, hated by the devil and the heavens / is buried here with his rotting corpse. He hated peace on earth, our faith he contested. / He ruined the church and the people.”

Francis Xavier (1506–1552)

Xavier’s early life gave no signal of his future as a traveling evangelist; he was born into wealth and privilege as the son of a high-ranking noble in Navarre (an independent kingdom between France and Spain). Spain’s conquest of much of the kingdom reduced the family’s power, and his father died when Francis was only nine.

However the Xaviers were still able to send Francis to the University of Paris. There, in 1529 at age 23, he roomed with a friend, Pierre Favre (we know him in English as Peter Faber). Soon the two young students welcomed a third roommate—38-year-old Ignatius of Loyola (see “Helping souls,” pp. 6–13).

Xavier did not think much of Ignatius at first, but his influence on the two roommates was so profound that five years later, on August 15, 1534, both Faber and Xavier met with Ignatius and four other students in a crypt beneath the Church of Saint Denis in Montmartre. They vowed obedience to the pope, poverty, chastity, and the intention of making a missionary voyage to the Holy Land. This marked the beginning of the Jesuits.

The accidental Jesuit soon became an accidental Jesuit missionary. King John of Portugal wanted to send missionaries to India and had been favorably impressed by the young students. One student chosen for the mission became sick at the last moment, and Ignatius appointed Xavier in his place.

Xavier sailed for India in 1542; he began his ministry there by preaching, visiting the sick, and walking through the streets ringing a little bell to attract children to catechism lessons. In the next 10 years, he journeyed throughout India, to the Maluku Islands and other Southeast Asian islands, deep into Japan, back to India, and finally toward China.

He got as far as Shangchuan Island off of the mainland and died there while waiting for a boat. The Catholic Encyclopedia said in tribute, “It is truly a matter of wonder that one man in the short space of ten years . . . could have visited so many countries, traversed so many seas, preached the Gospel to so many nations, and converted so many.”

Francis de Sales (1567–1622)

The second of the sixteenth century’s notable Francises, Francis de Sales was born into a noble French family. His father wanted his oldest son to become a lawyer or magistrate, and de Sales took lessons in riding, dancing, and fencing to please him, but he also began a theology degree, eventually graduating with a doctorate in law and theology at 25. His father got him a plum political appointment as a senator and arranged a marriage with a wealthy young noblewoman. But de Sales wanted to be a priest.

Ordained in 1593 he began missionary work in Chablais on the south shore of Lake Geneva, a Reformed area newly re-annexed by the Catholic duke of Savoy. He traveled on foot preaching and distributing short tracts. (For these efforts Catholics many years later made him the patron saint of journalists.) A large portion of the population eventually reconverted. In 1597 he even visited Geneva and debated Calvin’s successor, Theodore Beza, on a commission from Pope Clement VIII to try to win Beza back to Catholicism.

Order Christian History #122: The Catholic Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In 1602 de Sales was named bishop of Geneva. (He actually lived in Annecy, because the Reformed controlled Geneva.) Two years later he became spiritual director to widow Jane de Chantal (1572–1641). With his help she founded the Order of the Visitation in 1610, which worked actively in the world (they were later forced to become cloistered) and took in women too old, too young, or too sick to join other groups.

In his own day, de Sales was renowned as a preacher, spiritual director, and faithful bishop. Today he is most famous for his Introduction to the Devout Life (1609). Ironically for someone who had left law for religion, he wrote the book to encourage laypeople to seek holiness in their daily lives, noting: “It has happened that many have lost perfection in the desert who [would have] preserved it in the world.”

Charles Borromeo (1538–1584)

Borromeo decided on a church career at the age of 12. His family was related to the Medicis, one of Italy’s most notable political dynasties, but Borromeo supposedly told his father to spend on him only what was needed for his education and to give the rest to the poor.

In 1559 Borromeo’s uncle, Cardinal Giovanni Angelo Medici, became Pope Pius IV, succeeding the much-hated Paul IV (see above). He brought his 21-year-old nephew to Rome and made him “cardinal-nephew”—an official term denoting relatives of popes made cardinals, usually nephews or illegitimate sons.

Borromeo was charged with governing the Papal States and supervising the Franciscans, Carmelites, and other orders. He also helped his uncle organize the Council of Trent’s final session and handled its correspondence. One critical nobleman remarked, “Carlo Borromeo has undertaken to remake the city from top to bottom,” adding that the young bureaucrat would “correct the rest of the world once he has finished with Rome.”

When Borromeo’s older brother died in 1562, his family tried to get him to carry on the family name, but he rededicated himself to church service. Already administrator of the Diocese of Milan, he asked to be ordained a priest and made archbishop. His uncle the pope did not let him take up his duties until he had finished up details of the Council of Trent in 1565.

The new archbishop found his diocese in terrible moral and organizational shape. An archbishop had not visited for 80 years. Borromeo reduced the size of the archbishop’s household, reformed worship according to Trent’s decrees, and established seminaries for clergy. He also founded the Confraternities of Christian Doctrine, a Sunday school that grew to over 40,000 students in 740 schools with 3,000 teachers.

One powerful group who opposed Borromeo arranged to have him shot in the arch-episcopal chapel; fortunately the assassin missed. But many loved him, especially after he remained in Milan during a 1576 famine and plague, donating money to feed 60,000 people and repurposing church hangings to clothe them. In 1583 he cruelly attempted to suppress both Protestantism and witchcraft in Switzerland and also founded the Collegium Helveticum to educate Swiss Catholics. The next year, worn-out, he died of a fever at age 46.

Robert Bellarmine (1542–1621)

Bellarmine’s parents were well-connected but impoverished Tuscan nobles (Pope Marcellus II was his uncle). He joined the Jesuits in 1560 at age 22 and began to study philosophy at various universities, finally ending up at the University of Leuven in Flanders.

In 1576 Pope Gregory XIII recalled him to Rome to teach at the Jesuits’ Collegio Romano; Pope Sixtus V sent him to France in 1590 to assist in a diplomatic mission; and Pope Clement VIII gave him back his teaching job in 1592, then made him successively supervisor of a Jesuit province, papal theologian, examiner of bishops, and finally—saying he “had not his equal in learning”—a cardinal in 1599.

Sometime before 1593 Bellarmine completed his most famous work, Disputations on the Controversies of the Christian Faith, arguing against the divine right of kings and the supreme power of the pope in temporal affairs (it did not much please his boss).

After Sixtus died the count of Olivares wrote to King Philip III of Spain regarding Bellarmine as a possible new pope: “Bellarmine is beloved for his great goodness, but he is a scholar who lives only among books and not of much practical ability. … He would not do for a Pope, for he is mindful only of the interests of the Church and is unresponsive to the reasons of princes. … He would scruple to accept gifts. … I suggest that we exert no action in his favor.” Bellarmine continued to receive votes in conclaves as first Leo XI, then Paul V, then Gregory XV were elected—but never enough for election.

Today we remember Bellarmine most for an event that occurred in 1616. Pope Paul V asked the 74-year-old cardinal to speak to and correct the scientist Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), Bellarmine’s friend. The church was about to issue a decree condemning the Copernican “heliocentric” theory that the earth moved around the sun—a theory Galileo defended.

Bellarmine wrote to another heliocentric scientist, Paolo Antonio Foscarini: “If there were a true demonstration that the sun is at the center of the world and the earth in the third heaven, and that the sun does not circle the earth but the earth circles the sun, then one would have to proceed with great care in explaining the Scriptures that appear contrary. … But I will not believe that there is such a demonstration, until it is shown me.”

Five years later Bellarmine was dead. He did not live to see his friend Galileo called before the inquisition and convicted of heresy in 1633. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #122 The Catholic Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015&ndash2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Edwin and Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #122 in 2017]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is contributing editor at Christian History. Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor at Christian History. Visit ChristianHistoryInstitute.org to read bonus profiles of Reginald Pole and Gasparo Contarini, reprinted with permission from David C. Steinmetz’s Reformers in the Wings.Next articles

The Catholic Reformation: Recommended Resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you navigate the landscape of the Catholic Reformation and the effects of reform on into the seventeenth century.

the editorsThree featured paintings

Three paintings that put Comenius’s life and times in perspective.

the editorsChurch History in Brief

A capsule overview of the movement Jesus started, seen mostly from a Western perspective.

Bruce L. ShelleySupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate