Acid rain and Christian truth

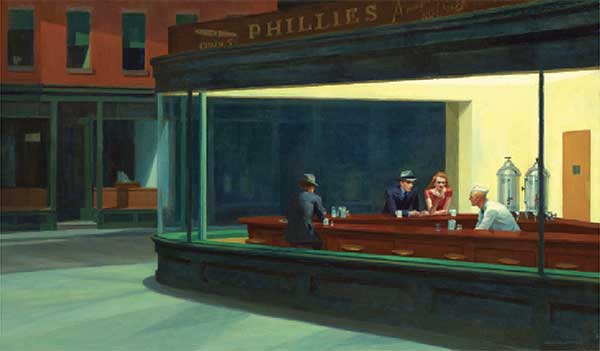

[Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942. From: The Art Institute of Chicago, Fifty-third Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture. Chicago, 1942]

WHAT COMES TO MIND when you hear the word “modern”? Probably something that is happening right now. Maybe you think of modern technology—smartphones or electric cars or robots. Actually things that are modern can be, paradoxically, much older than smartphones.

Scholars use “modern” as a label for the dramatic shift in Western society that occurred over the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Radical changes transpired during this three-century span that affected all aspects of Western life, with implications lasting into the twentieth century in areas like art, architecture, theology, and literature.

Scientific discovery and technological innovation exploded during the modern era. This led to a growth in industry, which heightened the standard of living and raised working-class incomes, causing a strengthened middle class to emerge. New political systems such as democracy appeared, giving common people legal rights once reserved for the aristocracy. Health standards increased, and life expectancy grew. Humans marveled at their own accomplishments, and enthusiasm spread for future possibilities. Still many saw flaws in this progress.

The rise of rationalism

“Insufficient facts always invite danger, Captain.”

—Lieutenant Spock on Star Trek

Premodern people assumed the Aristotelian principle that each of us is born with a clean slate and that all intellectual knowledge is acquired through an individual’s sensory experiences. In its Christian form, this principle taught that our interpretation of the world requires reliance upon revelation and tradition, accompanied by God-given reason illumined by the Holy Spirit. Faith must precede reason.

A motto coined by St. Augustine of Hippo and later credited to St. Anselm of Canterbury sums up the idea: “I believe in order to understand.” C. S. Lewis said something similar in his essay “Is Theology Poetry?”:

I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen, not only because I see it but because by it, I see everything else.

Central to modernity was the rise of a new rationalism in philosophy and science, focused solely on what the human mind could understand through reason alone. This owed much to the spread of “Cartesian epistemology,” a thought system developed by philosopher and scientist René Descartes (1596–1650).

Descartes represented a major break with the past. He declared that feelings, sense perceptions, and tradition are deficient sources of facts. In Descartes’s assessment knowledge is attained solely by reason. The senses can be deceptive, he believed, and revelation and tradition are not dependable. Reason alone determines knowledge; everything else is either bias, opinion, or superstition.

While not all modern philosophers agreed with Descartes, his influence on the modern worldview was pervasive. He paved the way for thinkers to presume society could reform through the use of objective reasoning and logic, and for them to challenge ideas that previous generations had grounded in tradition and faith. Instead they sought to advance knowledge through rationality and the scientific method.

As a result modernist thinkers believed they possessed new knowledge that allowed them a privileged position to judge the errors of the past and advance into an improved, more excellent future. They favored the natural world in place of the supernatural, progress in place of tradition, and the secular in place of the sacred.

The acids of modernity

Undeniably this trend radically affected the Christian faith. The “acids of modernity” (as political commentator Walter Lippmann called them) ate away at traditional Christian convictions and rituals. In his book Religion and the Enlightenment, James Byrne named three significant ways modernity was at odds with traditional Christian orthodoxy.

First the emphasis on the power of reason to discover the truth about humanity and the world posed a threat to traditional Christian belief. The modern ideal was a Lieutenant Spock–like figure, able to follow logic and reason wherever it led without any influence of personal bias. The peril for the church of such exclusive focus on rationality and logic was the rejection of all authoritative claims of revelation, faith, and tradition.

Modernity called into question the credibility of biblical witness, historic testimony, and religious authority: if something about the Christian faith doesn’t make rational sense, then it can’t be true. Many modern thinkers applied and continue to apply this even to such crucial elements of faith as Christ’s divinity and his Resurrection.

The second challenge modernism posed to Christian orthodoxy was skepticism toward institutions of the past. As a general rule, modernity encouraged suspicion of any traditional truth claim regardless of the source of the claim: tradition must be scrutinized and sometimes rejected in favor of more rational approaches to knowledge.

The temptation for the church was to no longer rely on traditional doctrines as authoritative. Ultimately this led to a fractured and individualistic approach to faith. If the church throws out tradition, then each person is free to define truth for himself or herself.

The third characteristic of modernity potentially corrosive to the church was the emergence of a scientific way of thinking that many feel gives a viable alternative to religion in understanding how the world works. Naturalism asserts that natural laws rather than spiritual laws rule and govern the universe: because humans can prove how the world works through the use of science, there is no longer need for a reigning and ruling God.

While the church did not fully buy into the dismissal of everything divine, it did begin to question certain supernatural elements of Christian faith: the miraculous and the sacramental. The old perception of the natural world as “charged with the grandeur of God” yielded inch by inch to the dominant claims of scientific reason. Rearguard actions continued—such as the nineteenth-century romantic movement of Gerard Manley Hopkins (author of “God’s Grandeur”) and the twentieth-century literary revival by Chesterton, Lewis, and Tolkien. But ultimately for many Christians, naturalism resulted in a disenchantment with the world. Science, it seemed, could now answer the big questions without God.

New ways? Old ways?

In light of the challenges posed by these “acids of modernity,” Christian thinkers felt they had to find new ways to articulate the Christian faith. Over time two primary responses emerged. The first denied anything supernatural in Christian belief. This has become known as “theological liberalism” or “liberal theology.”

Many modern religious scholars were unable to reconcile the contradictions they saw between science and the Bible, reason and the Bible, and historical evidence and the Bible. Therefore to discover the true core of Christian faith, they deemed it necessary to “demythologize” Christianity—denying any supernatural elements such as miracles or the Resurrection of Jesus. Many liberal theologians ultimately explained growth in virtue as the sole purpose of the Christian faith, with Jesus Christ as a role model.

A second reaction to modernity came from a part of the church unwilling to let go of the foundational, creedal, and biblical beliefs of Christianity. This group of conservative theologians applied what was called “evidential apologetics,” a proof-oriented defense that rationalized the faith.

They sought to convince people of the truth of Christian belief by building structures of certainty for faith-based claims: critical defenses of biblical texts, defenses of the doctrine of inerrancy, discoveries in archaeology, and other analytical proofs of Christianity. Some also elevated personal experience above everything else as decisive evidence of the sure presence and work of God.

In their effort to fight against modernity, however, they often employed the same purely rational approach to Christian faith. Ultimately neither approach knew what to do with many ancient doctrines, liturgies, and practices of the church.

Looking backward

All reform begins with looking forward in dissatisfaction. Something is amiss and needs to be righted. But reform also begins by looking backward—or at least the church has functioned this way over its long history. Christians throughout the ages—from Augustine to Martin Luther, John Calvin, and John Wesley—have viewed the past as a trustworthy guide (see “Did you know,” inside front cover). The past can show us where things have gone astray and how they can be corrected.

In the twentieth century, many Christian thinkers began to look forward by looking back. We’ll meet many of them on the following pages, but we’ll begin by considering two of their journeys as paradigms for helping us understand this return to orthodoxy—especially its impact on evangelicalism.

United Methodist theologian Tom Oden (1931–2016) was highly influenced by modernity early in his career. For Oden the study of ancient Christianity ultimately led him out of the disillusionments of modernity and toward the recovery of Christian orthodoxy (see “He made no new contribution to theology,” pp. 10–14). In his autobiography, A Change of Heart (2014), Oden wrote,

Before my reversal, all of my questions about theology and the modern world had been premised on key value assumptions of modern [liberal] consciousness—assumptions such as absolute moral relativism.

After meeting new friends in the writings of antiquity, I had a new grounding for those questions. . . . I have come to trust the very consensus I once dismissed and distrusted. Generations of double-checking confirm it as a reliable body of scriptural interpretation. I now relish studying the diverse rainbow of orthodox voices from varied cultures spanning all continents over two thousand years.

Baptist-turned-Anglican professor Robert Webber (1933–2007), meanwhile, was dissatisfied with evangelicalism’s overly rational, cognitive, and sermon-centric approach to worship (see “The road to the future runs through the past,” pp. 16–19). He felt that this resulted in a pastor-dominated, human-centered, ethereal, nonparticipatory gathering.

The pathway to reform, as Webber wrote in Common Roots (1978), is “to face the negative task of overcoming . . . modernity, while on the other hand . . .

[to] grow into a more mature and historic expression of the faith.” In his own study of the first five centuries of the church, Webber discovered the fully orthodox Christianity he had longed for.

Tested truth

All the thinkers you’ll meet in this issue believed that the ancient faith of the church has regenerative power for the church today and that the long memory of tested Christian truth tends to eventually override the shorter memory of error.

They stepped back behind Descartes and the flaws they saw in rationalism to learn from teachers such as Irenaeus, Augustine, and John Chrysostom. As they did so, they learned how to rightly guard, reasonably vindicate, and wisely advocate the faith once delivered to all the saints—so that the church would not concede to the spirit of the times but rather respond to the times, overcoming any doubt or error that may threaten it. C H

By Jonathan A. Powers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #129 in 2019]

Jonathan A. Powers is assistant professor of worship at Asbury Theological Seminary and the author or editor of several resources that draw on church tradition for modern use.Next articles

“He made no new contribution to theology”

Tom Oden’s influential return to orthodox faith.

Christopher A. HallFulfilling a longing for the early church

An excerpt from Oden's Ancient Christian Commentary

Thomas C. Oden and Christopher A. HallTaking the long view back

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century renewal and cooperation

Jennifer Woodruff Tait“The road to the future runs through the past”

Bob Webber and the “ancient future” of American evangelicalism

Joel ScandrettSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate