“A long drink of cool water”

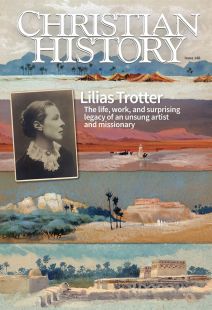

[Photograph of Lilias Trotter at Tozeur, 1923—Used by permission of Lilias Trotter Legacy and Arab World Ministries of Pioneers]

Miriam Huffman Rockness, chairman of Lilias Trotter Legacy, reflected further with CH about Trotter’s history and her impact.

Christian History: Talk to me about Trotter’s connections to the Victorian spiritual environment.

Miriam Huffman Rockness: Trotter and her mother were two of 100 people gathering at Broadlands, which eventually evolved into the Keswick conferences. Her practical theology was formed at Keswick. At the same time, she was involved in the Moody-Sankey revivals in London—even the Queen attended one out of curiosity. People in Broadlands prayed for Moody and he prayed for them. There was a spiritual synergy. This changed everything for her, a spiritually responsive and tender soul who already had a heart for service. Social work at that time depended on volunteerism.

Trotter, like many young women of wealth, volunteered, but she took it to the next level. Many women she worked with became supporters through her life of ministry in Algeria. After she resolved the role of art in her life, she went back to this London work with renewed fervor and dedication. She had very little interest in foreign missions. But then in the 1880s, at a meeting inspired by the Cambridge Seven, a missionary from Algeria came and presented the vision, and her heart stirred at the words “North Africa.”

Even on the field, she was well connected. She loved to keep up with what was going on in London. She kept her mind fertile and active and interested. Samuel Zwemer attributed to Lily many of the things he learned about how to minister. She helped him with the development of literature for the Arab world and went to Egypt for several months to work with the Niles Mission Press. And then she was involved in John Mott’s Constantine conference in North Africa and his Jerusalem conference. The International Sunday School Convention also took an interest in her work in Algeria.

CH: She didn’t really “give up art,” did she?

MHR: When Ruskin said he would personally mentor her career with the caveat that she devote her entire life to painting, we can’t even imagine how heady that must have been for her: he was the arbiter of art of the Victorian age. And he was a great man. He was an odd man, but had a great vision. And he wasn’t giving her an unreasonable challenge. Anyone who’s going to excel at that level would have to be single-minded. She tried to balance the artistic part of her life and the mission part and realized she could not do both at the same level. But she could use art as a missions tool and as something that allowed her to process life and beauty.

I think we don’t know what would have really happened had she devoted her life to art. In the Victorian era, a woman really was working at a disadvantage, even with Ruskin advocating. Look at the Pre-Raphaelites: there were women artists among them, but they often ended up as models, such as Elizabeth Siddal, the model for Millais’s Ophelia.

CH: And Ruskin scholars have become interested in her?

MHR: Trotter was a missing piece in Ruskin scholarship. Kenneth Clarke’s Ruskin Today (1964) assumed she was just another one of these young women who came in and out of his life that he was dazzled by, who came to no account. One of the great privileges of my life was telling these scholars the rest of the story. She has been of great interest to the Ruskin community; I’ve spoken at several Ruskin conferences.

Dr. Steven Wildman, director of the Ruskin Library and Research Centre, evaluated her art. He said she had a remarkable capacity to record quickly what she saw, even from a train or on a camel. She also had the ability to take something of immense size, a desert or a mountain, and contain it into something as small as a postage stamp. And she had a unique ability to juxtapose art with words. He summed it up by saying she had what every artist longs for (and she had it from a very early age): a voice. Two years ago, a man said he’d just bought 21 Trotter paintings at an auction. I very much doubted it. But the moment I saw them, I knew it was Lily. It was amazing. (These paintings can now be seen in the Special Collections of Wheaton College.)

CH: How would you describe the common thread of her life?

MHR: There was breadth to her vision without compromising her own view of the gospel. There was broadness of spirit, an openness to the ideas of others, particularly young people.

She was incarnational; she lived with the people to whom she ministered. She prayed. She developed materials so other people could pray. She had rooms of prayer, so workers could pray no matter how busy they were. She must have been a tremendously disciplined person to do all the things she did and still have time. On our website we have editorials she wrote to her missionaries called “The Letter M.” It comes as close as we’ll ever get to understanding her philosophy of mission. One of the things she challenges them with is the use of time. You have the sense that she had a high standard for herself, but she held that up to her workers as well.

She had a sense of eternity like very few people I have read. And a sense of beauty: seeing the Creator, seeing his works, reading his world as another textbook. (She was reared by a father who had a scientific bent and loved reading scientific books.) Even “Focussed” was based on the law of optics: when you focus on one thing, other things become blurry and dim.

CH: Are some parts of her legacy now just taken for granted?

MHR: In so many ways, she was ahead of her time: short-term missionaries, the literature she wrote, cross-cultural understanding, coffee houses, handcrafts for financial independence. Her ministry to the Sufis is relevant today for people who are interested in spiritual things but are not looking to define them; she gives that hunger and love for the spiritual a scriptural foundation. She never did see her stated goal, a church visible in Algeria, during her lifetime, but got glimpses. Now there is a church visible in Algeria! Not without opposition, but definitely gathered in formal settings for worship across the country. Missionaries today tell of sensing a “prepared place” where the ground seems “cultivated.”

CH: If you were telling somebody why they should encounter Trotter, what would you say?

MHR: I believe she’s countercultural. Even in the Christian community, it’s not easy to withstand secular expectations of what is successful and important. When Lily came into my life, she struck the deepest chord. Truth is not about size. It’s not about numbers. It’s not about recognition. It’s about faithfulness. People can mean that in a very blurry and unsubstantial way. But when it’s coming from a person who has all the options in the world and has chosen this path with joy, it resonates deeply for me, like a long drink of cool water. I feel that in an age when young people are longing for authenticity and older people are looking for meaning and purpose, Lily has a message that resonates—pointing to beauty, the glory of God, and the joy we can have in living in communion with him. CH

By Miriam Huffman Rockness and the editor

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Miriam Huffman Rockness is chairman of the Lilias Trotter LegacyNext articles

Recommended resources: Lilias Trotter

Read more about the life and work of Lilias Trotter, and about Victorian art, piety, and mission, in these resources recommended by our authors and CH staff.

the editorsDid you know? Medieval Renewal

Can we use the word “revival” about medieval movements for renewal?

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate