“God will bless us in doing right”

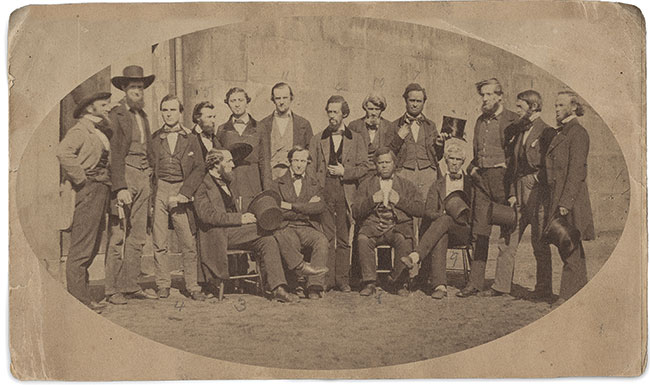

[Oberlin Rescuers, 1859—Courtesy of Oberlin College Archives]

On September 13, 1858, a group of about 600 people gathered together in the small town of Oberlin, Ohio, and traveled—some even on foot—to the nearby town of Wellington to save a neighbor. The day before, John Price had been arrested as a fugitive slave and was being held at a hotel in Wellington.

The crowd, which included professors and students from Oberlin College, converged on the Wads-worth House hotel and helped Price escape through a window. They took him back to Oberlin and hid him in the house of James H. Fairchild (1817–1902), a professor and future president of Oberlin College.

Several months later Price was escorted to freedom in Canada. Of the 600 people who helped rescue Price in defiance of the Fugitive Slave Law, 37 were arrested, indicted, and jailed—including Oberlin College’s professor of ethics and the Oberlin Sunday School superintendent. The jailed men started an abolitionist newspaper called The Rescuer, which they published during the three months of their incarceration.

Peculiar good

The town of Oberlin had been founded by John Jay Shipherd (1802–1844) and Philo P. Stewart (1798–1868) who bought land in Ohio to establish a utopian society “peculiar in that which is good.” The members of Oberlin Colony, a mixture of New England Congregationalists and revivalist Presbyterians, believed a school that would promote “earnest and living piety among the students” would help students grow in holiness and spread social reform ideals. In the fall of 1833, the Oberlin Collegiate Institute published its vision:

The grand (but not exclusive) objects of the Oberlin Institute, are the education of Gospel ministers and pious school teachers. . . . The system of education in this Institute will provide for the body and heart as well as the intellect; for it aims at the best education of the whole man.

At the heart of the Oberlin Institute was the belief that authentic Christianity is not only a set of beliefs but a commitment to action. As a result, from the beginning, the institute committed to social reform as the true expression of the gospel. Evangelist Charles Finney (1792–1875) served as a professor at Oberlin from 1835 on and as president from 1851 to 1866. His thinking, regularly expressed in the Oberlin Evangelist, articulated the institute’s understanding of the church’s vocation in the world:

The Christian church was designed to . . . lift up her voice and put forth her energies against iniquity in high and low places—to reform individuals, communities, and governments, and never rest until the kingdom and the greatness of the kingdom under the whole heaven shall be given to the people of the saints of the most High God—until every form of iniquity shall be driven from the earth.

Oberlin Institute leaders tried to create a space where future Christian leaders could practice holiness and piety individually and communally so that when they went out into the world they could produce the “greatest amount of moral influence.” As a result they championed various social reform movements (coeducation, advocacy for Native Americans, the peace movement, temperance, and dietary reforms) but are perhaps most well known for an early and serious commitment to abolition, a position that solidified following an uprising at another Ohio school.

Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, founded by Presbyterians in 1829, envisioned itself a “great central theological institution” in the West. But when in 1834 the school tried to stop students from abolitionist activities, the bulk of the student body resigned en masse. These students, along with professors John Morgan and trustee Asa Mahan, became known as the Lane Rebels. They had financial support from wealthy New York businessmen Arthur (1786–1865) and Lewis Tappan (1788–1863), but no school to call their home.

Shipherd, sensing an opportunity, invited the group to join the Oberlin Institute, and they agreed. The arrival of these students and their advocates, with their commitment to abolition and equality, had an immediate and long-lasting influence on the school’s ethos. John Morgan was invited to become a professor at Oberlin Institute, Asa Mahan (1799–1889) became the institute’s first president, and the Tappan brothers gave their financial assistance to the institute. In addition to this, the Tappans encouraged Finney to join the faculty of Oberlin’s theological department.

“A matter of great interest”

All of this support hinged on Oberlin agreeing to admit Black students. Those invested in Oberlin (students, faculty, trustees, and townspeople) were divided over this, but Shipherd used his typical blend of revivalism and pragmatism to convince the trustees to vote in favor of it, writing,

This should be passed because it is right principle; and God will bless us in doing right. Also because thus doing right we gain the confidence of benevolent and able men who probably will furnish us some thousands.

In February 1835 the Oberlin trustees passed the following resolution by a majority of one vote:

That the education of the people of color is a matter of great interest and should be encouraged & sustained in this Institution.

Oberlin immediately began admitting Black students along with White students. According to Oberlin’s leaders, this was a distinctive decision in the fight for racial equality. They believed that segregation itself, not simply lack of education, disadvantaged Black Americans while simultaneously allowing White Americans to remain undisturbed in their racism. Oberlin professor and president James Fairchild wrote that the goal of Oberlin for the Black student was to the extent of its influence, to break down the barrier of caste, and to elevate him to a common platform of intellectual, social, and religious life. This result it aims to secure, by admitting him, without any reservation or distinction, to all the advantages of a school, having a fair standing among the colleges of the land. Such a work, a distinctively colored school could not effect.

From 1834 to 1875, Oberlin fully admitted Black students into classes, room and board, college work programs, and scholarships. Perhaps one of the most scandalous aspects at the time was room and board: Black students both lived and ate with White students.

When White students complained about eating at the same table as Black students, the faculty agreed that the complainers could sit at a table designated only for them. This separate table was designed to display their prejudices to the whole school and put them in what Finney called “an awkward position.” It wasn’t long before the table was no longer requested.

Although throughout the nineteenth century the number of Black students at Oberlin rarely exceeded 5 percent of the student body (it hit its high point at about 8 percent in the 10 years after the Civil War), by 1899 Oberlin had graduated 128 Black students. Of other White-majority northern schools, the next closest was the University of Kansas with 16 Black graduates.

But Oberlin’s commitment to racial equality faded following Reconstruction. Gone was the generation of the Rescuers and those they influenced. Oberlin graduate Mary Church Terrell sent her daughters to Oberlin in the early 1900s only to discover they were now required to live in all-Black housing. In 1913 she wrote to the dean of women,

I do not believe in segregation of any group of students on account of race or color or anything else for which they are not responsible. I do not want my daughters segregated in Oberlin College. I believe segregation is unchristian, unjust and unkind. . . . When I attended Oberlin College, no one could have made me believe that the day would ever come, when colored students would be segregated.

“Losing our faith”

Oberlin recommitted to racial equality in the twentieth century, but Oberlin’s belief that Christian revival was the key to social reform faded and then disappeared. Oberlin president William Stevenson (1946–1960) was the last president to call for social justice on the basis of Christianity. In his 1947 inaugural address, he said, “‘So long as we condone or permit racial or any type of intolerance we run the risk of losing our faith.’” Oberlin’s focus on “a sustainable and just society” (as today’s mission statement phrases it) was reawakened and redirected in the years after World War II, but the basis for such work became secular, rather than Christian, ideals. CH

By Christina Hitchcock

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #139 in 2021]

Christina Hitchcock is professor of theology at the University of Sioux Falls and author of The Significance of Singleness.Next articles

Delicate balance

Fundamentalist heritage and the evangelical mind at Wheaton College

George M. MarsdenSeeking and teaching virtue

Christian bearers of the liberal arts tradition from the Middle Ages to the present

Jennifer A. BoardmanHumility, truth, mentoring, love

Is something missing from the modern university?

the editors and intervieweesSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate