ALLEN USED HEALING TO SPREAD CHRISTIANITY IN KOREA

[Above: Horace Allen (tall and bald) at the center of diplomatic officials in Seoul—Horace N. Allen, Things Korean: A Collection of Sketches and Anecdotes Missionary and Diplomatic. New York, Chicago, Toronto, London, and Edinburgh: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1908. Public domain.]

AFTER A PONY RIDE that “nearly killed” him, Horace Allen arrived at Seoul, Korea, in September 1884. A physician of the American Presbyterian Mission, he knew Christianity was illegal in the Confucian nation. Indeed, numerous Catholic Christians and a few isolated Protestants had suffered death for their faith. Consequently, Allen used the cover of physician to the US legation, hoping that Providence would open doors for him.

Providence did. On 4 December 1884 Min Yong-ik, a nephew of Korea’s queen, suffered seven sword-thrusts during an assassination attempt. In Allen’s words:

Dec. 4 Emeute [uprising] of Kim Ok Kiun, followed a banquet given in honor of the opening of the Post Office. Min Yong Ik was cut down and five high conservative Korean officials and others were assassinated. The progressive party headed by Kim Ok Kiun seized the Palace.

Allen worked all night to save Yong-ik’s life. Over the next few days he attended Yong-ik several times more as well as treating twenty Chinese soldiers wounded defending the monarchy. Some of these men experienced astonishing recoveries that Allen attributed to prayer.

Although the reformers wanted to implement western-style reforms, they held power just one day. All the same, Seoul’s American delegation soon retreated to the coast, urging Allen to pull out with them. He refused, saying he had come to Korea for just such emergencies as this and would trust his life to Christ. With his wife Fannie (who had recently joined him), and their infant son, he remained.

The king and queen solicited his medical services. Only a person of Champan rank (Mandarin) could be presented to a king, who offered the rank to Allen. Allen mulled the offer. Tending royalty could be dangerous, because if his medical expertise failed, reprisals might be severe. In the end, however, he accepted. On this day, 25 October 1885, one year, one month, and one day after his arrival, Korea raised him to Champan rank.

Swamped by requests for medical attention, Allen proposed the foundation of a western-style hospital to train Koreans in medicine and sanitation. He saw it as a way to get a foothold for introducing Christianity. The king warmly approved the suggestion. When the hospital opened, Allen found himself handling twenty to sixty cases a day, including up to six surgeries, all while training students. The overload took a toll: “My stomach also makes me cross & irritable and not a good missionary.”

Coworkers found him difficult, and he had an on-again, off-again relationship with the Presbyterian mission. Eventually he severed formal ties and between 1890 and 1905 he worked as a diplomat. Superiors in Washington chided him more than once for disobeying orders, and finally President Teddy Roosevelt recalled him, probably because Allen spoke against Roosevelt’s pro-Japanese policy.

Koreans, however, honor Allen, and many recognize his name. Plaques throughout the nation remember him, because in addition to introducing modern medicine and the Presbyterian Church to Korea, he encouraged improvements in public utilities, mining, and communications. He compiled the first Korean-English dictionary and a book of Korean folk tales. One, “Hong Kil Tong, or, the Adventures of an Abused Boy” blends elements familiar to western readers: resentment of a concubine’s son (Jephtha); robbing the rich for the poor (Robin Hood); assistance by spirits and magical transportation (Arabian Nights); and rescuing a damsel in distress with love at first sight (a theme at least as old as Jacob meeting Rachel or Perseus rescuing Andromeda).

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

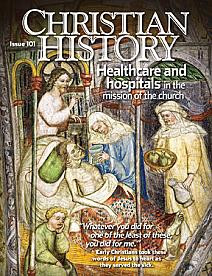

The church has often won souls through medicine, a story told in Christian History #101, Healthcare and Hospitals in the Mission of the Church