ARTHUR TAPPAN SPREAD HIS WEALTH FOR GOOD CAUSES

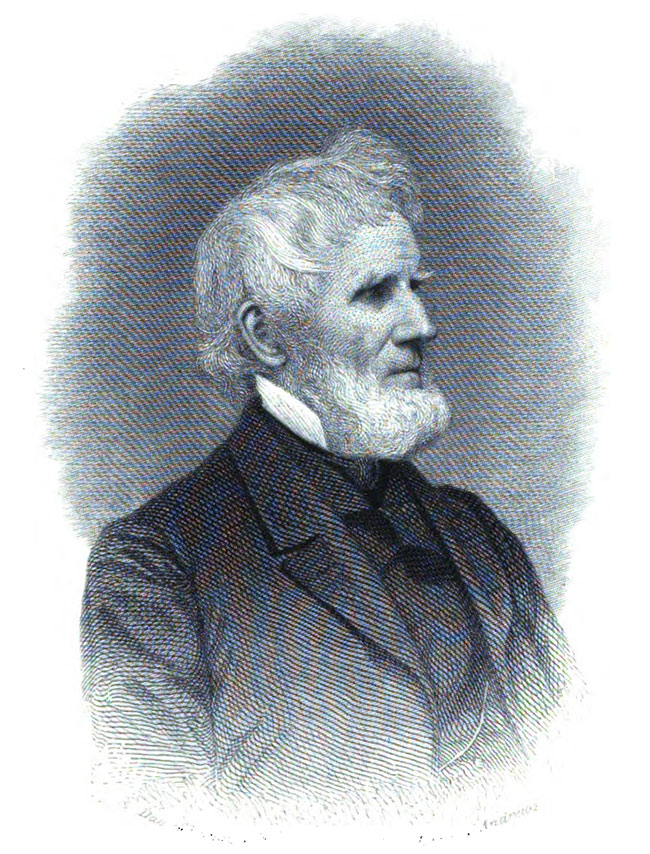

[Above: Arthur Tappan, from The Life of Arthur Tappan by Lewis Tappan. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1870. public domain]

THROUGH HARD WORK, perseverance, and strict honesty, Arthur Tappan became wealthy. In the mid-nineteenth century, he did a million dollars’ worth of business each year in dry goods. By a conservative estimate, that would equate to twenty-five or thirty million dollars today.

A series of business failures owing to war and financial crashes forced him to innovate. He was one of the first to insist on fixed prices and to sell only for cash or short credit. After each reverse, he tightened his belt, worked longer hours, and paid back his creditors. Following the Panic of 1837, he and his brother Lewis founded the first commercial credit-rating service, a precursor of Dunn and Bradstreet.

Deeply Christian, Tappan used his income for good works. Among the causes he championed were education (including theological seminaries and schools for African Americans) and missions. He urged Sabbath observance, supported an effort to reclaim prostitutes, and worked to prohibit sales of alcoholic beverages and to end tobacco use. He even founded the New York Journal of Commerce to provide the city a newspaper free of advertisements for worldly indulgences. However, the cause he championed most ardently was the abolition of slavery.

In the troubled decades before the Civil War, to stand for abolition—even in a northern state—could be costly. Abolitionists were threatened, jailed, and even killed. Newspapers lied and slandered them. Mobs burned their homes, churches, or businesses. Boycotts reduced their trade. Tappan encountered most of these reactions.

By 1833, abolitionist newspapers had awakened many New Yorkers to the evils of slavery. Tappan and his friends felt the time was ripe to form a society to expand their fight to end slavery. They rented a hall and advertised in newspapers and on posters.

Pro-slavery forces countered by scheduling a meeting of their own at the same time. Frightened, the owner of Clinton Hall canceled the abolitionists’ reservation. No one else would rent them meeting space. Finally, they obtained access to Chatham Street Chapel. On this day, 2 October 1833, about fifty of them met and drafted their constitution.

Meanwhile pro-slavery agitators went to Clinton Hall. Finding it shut, they gathered near Tammany Hall. In fiery speeches they denounced the abolitionists. Then they learned that Tappan and his group were at the chapel. “Let’s rout them!” they shouted. A mob of two thousand rushed to the scene but found themselves barred by iron gates. While Tappan’s group slipped out a back door, the janitor opened the front gates to the mob.

Prearranged articles in newspapers gloated that Tappan’s efforts were defeated. However, a committee of the abolitionists worked late that night and prepared their own account for the morning papers. The Journal of Commerce reported,

[The] emancipationists outgeneraled their opposers; for while the latter were besieging Clinton Hall, or wasting wind at Tammany Hall, the former were quietly adopting their Constitution at Chatham Street Chapel.

They had but just adjourned, we understand, when the din of the invading army, as it approached from Tammany Hall, fell upon their ears; and before the audience was fairly out of the chapel, the flood poured in through the gates as if they would take it by storm. But they were too late; the Anti-Slavery Society had been formed, the Constitution adopted, and the meeting adjourned! So, they had nothing to do but go home.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

Arthur and Lewis Tappan appear in "Charles Grandison Finney: A Gallery" in Christian History #20, Charles Grandison Finney

Never miss an issue of Christian History. Subscribe now.