Who you gonna call?

THE ROMAN WORLD in the early Christian era was frequently troubled by plagues; the most famous and destructive of these broke out in 250 and lasted 15 years. Epidemics of plague are reported in a number of cities in the second through fourth centuries. In at least some cases, they were diseases brought back by Roman troops returning from far-flung campaigns. Some may have been versions of smallpox or measles.

Frequently, shrines and oracles of the Roman gods were consulted in efforts to learn what would stop the plagues. Some shrines, like the one to Apollo at Didyma, were established to thank a god for saving a city from plague. Things that terrified the populace, says historian Robin Lane Fox, made “excellent business for Apollo.”

Christians were often blamed for causing epidemics because they refused to do pious acts appeasing the gods. Tertullian famously wrote (around 196) in his Apology: “If the Tiber rises as high as the city walls, if the Nile does not send its waters up over the fields, if the heavens give no rain, if there is an earthquake, if there is famine or pestilence, straightway the cry is, ‘Away with the Christians to the lion!’” In around 270, says historian Steven Walton, Porphyry blamed a plague in Rome “on the fact that the temple of Aesculapius [Asclepius, the god of medicine and healing] had been abandoned for the Christian churches.”

Eusebius reported on a plague during the reign of the emperor Maximinius II (303–313): “A great rural population [was] almost entirely wiped out; nearly all being speedily destroyed by famine and pestilence . . . Some, chewing wisps of hay and recklessly eating noxious herbs, undermined and ruined their constitutions. And some of the high-born women in the cities, driven by want to shameful extremities, went forth into the market-places to beg.”

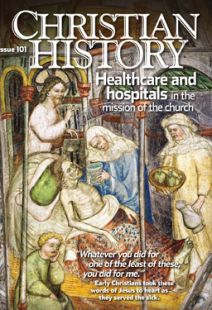

In the crisis, the Christians knew what to do. Eusebius reported proudly on his fellow believers’ response: “Then did the evidences of the universal zeal and piety of the Christians become manifest to all the heathen. For they alone in the midst of such ills showed their sympathy and humanity by their deeds. Every day some continued caring for and burying the dead, for there were multitudes who had no one to care for them; others collected in one place those who were afflicted by the famine, throughout the entire city, and gave bread to them all.”

By The Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #101 in 2011]

Next articles

How the King James Bible brought a “fly in the ointment” to English

From the “skin of your teeth” to “sour grapes,” many English idioms are Hebrew sayings the KJV translated literally

Alistair McGrathWas Paul against sex?

The plain sense of a KJV text from one of his letters certainly seems to prove it. But wait . . .

Roger L. OmansonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate