Two Takes on the KJV

HISTORICAL DOCUMENTARIES inhabit two worlds as they blend entertainment and information. In the world of the written word—strong in its ability to convey information—the artist always faces a challenge to appeal to readers’ senses and arrest their attention. In the world of dramatic film—with its ability to portray action, convey tone of voice, and deliver visual and audio stimulation—the artist faces a challenge to slow down enough to engage the brain along with the eye and the ear.

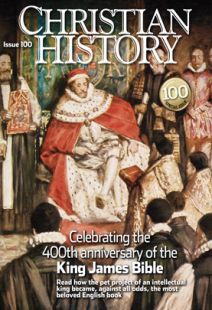

Two new films on the King James Version tilt in opposite directions as they try to exploit film’s possibilities while teaching viewers about a monumental 17th-century event.

KJB: The Book that Changed the World (Lionsgate), produced and directed by Norman Stone (Florence Nightingale, C. S. Lewis: Beyond Narnia), tilts toward arresting dramatic reconstructions. Robert Cecil cajoles the aging Elizabeth and orchestrates the transition to the newly crowned James I. Young James spars with his strict Calvinist tutor about the observance of Epiphany. The newly crowned James I colorfully abuses both bishops and Puritans at the 1604 Hampton Court conference. (Luther-like, James calls the Puritan requests “a litany of dullness blown out your buttocks.”)

The film capitalizes on dramatic developments (which keeps it from exploring historians’ challenges to the story that the Gunpowder Plot conspirators tried to tunnel under Parliament). Colorful host/narrator John Rhys-Davies (The Lord of the Rings’s Gimli the Dwarf) intensifies the drama with his grand manner.

For all its theatrics, however, the film doesn’t show the drama of translation itself. For that, we have KJV: The Making of the King James Bible (Vision Video).

With a minimum of historical context and at only half the length of Stone’s 90-minute treatment, KJV: The Making of the King James Bible provides text samples from the Bishops’ Bible (a lazy translation from Elizabeth’s reign), the Geneva Bible (a rigorous but agenda-laden translation built on the foundations of William Tyndale), and the Latin Vulgate (the 1,200-year-old official Catholic Bible). In Psalm 23, does the Lord lead me as a shepherd? Or does he rule me? In I Cor. 13, does Paul praise the virtues of love or of charity? Theology and political philosophy will color the expectations of the translator. Are society’s leaders to exercise care or dominion? Is the Christian life about affection or good works? The choices favored by the Puritans, says Adam Nicolson, author of the 2003 book God’s Secretaries, are deeply subversive.

Nicolson is one of the best things about this film. Each documentary has its lineup of experts, but Nicolson’s wit and chipmunkish charm trumps them all. While Stone’s film plays Bishop Richard Bancroft as a scheming comic villain, Nicolson roots Bancroft’s ruthlessness in his rough, rural Cumbrian origins. While Stone presents a James who protects his power by imposing his will on the competing religious parties, Nicolson gives us a wily James who grants the Puritan leader John Rainolds only one request—a fresh translation of the Scriptures—and then hands the Puritan project to Rainolds’s nemesis Bancroft for implementation. By forcing the parties to work together, he hoped to bridge the gap.

The triumph of the KJV, both films point out, was more in its craftsmanship than in its popularity. It took a nation torn by civil war and wounded by both monarchist and Puritan excesses to embrace the KJV some 50 years later as a symbol of religious unity.

By David Neff

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #100 in 2011]

David Neff is editor of Christianity TodayNext articles

A nation on a hill?

The history of church-state relations in America has been both complicated and contentious

Gary Scott SmithHow the King James Bible was Born

King James gave the Puritans almost nothing of what they wanted, except a new Bible translation

A. Kenneth CurtisSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate