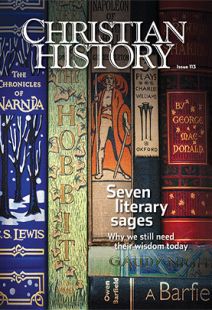

The poetic vision of a connected world

IN 1939 a book appeared under the title The Descent of the Dove. It was by Charles Williams, and it was a history of the Christian church. But it was a history like no other history. Dedicated to “The Companions of the Co-inherence,” it began with the cryptic motto “This also is Thou; neither is this Thou.” Williams claimed to be ignorant of its source but commented provocatively: “As a maxim for living it is indispensable and it—or its reversal—summarizes the history of the Christian Church.”

The Descent of the Dove offers a unique perspective, not simply because of its mysterious motto but also because it was written by a poet. Poetry was Charles Williams’s first and greatest love, a compelling and defining presence throughout his life in whatever genre he expressed himself: fiction, drama, biography, theology, history. The headstone of his grave in Oxford bears the simple inscription “Charles Walter Stansby Williams 1886–1945 Poet Under the Mercy.” To readers not alert to poetry’s demands of special attentiveness and imaginative alertness, his writing often seems opaque and even puzzling.

Williams was not a scholar like his friends C. S. Lewis and Dorothy L. Sayers. He was most decidedly a man of ideas and profound intellectual convictions, but he expressed his ideas very differently than they did. In Lewis and Sayers we find nonfiction that presents clear, direct philosophical or theological argument. Williams’s prose strikes us as dense, paradoxical, full of allusions and elusive ideas.

One of the most central of those ideas is what he called “co-inherence”: a profound interdependence that Williams thought of as a fundamental fact of existence. Our interdependent life forms the reality behind the stuff of creation and is a defining quality of God, who as a Trinity exists in relationship. But it was most gloriously displayed and brought to perfection in the birth, life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ. What is true of the inner life of the Holy Trinity became, in the Incarnation, the ultimate form of the relationship between God and humanity.

In The Descent of the Dove, Williams named St. Paul as the first Christian to give expression to this mystery, fastening on the statement, “Bear ye one another’s burdens” (Gal. 6:2). Williams commented, “In such words there was defined a new state of being. A state of redemption, of co-inherence, made by divine substitution, ‘He in us and we in Him.’”

“Another will be in me”

Over and over again throughout the book, Williams gave intense and delighted scrutiny to events that demonstrate the truth of “He in us and we in Him,” whether they form part of more traditional church histories or not. An apparently obscure, unimportant person or occurrence opens up a window on deep mysteries of our being.

For example, as he surveyed Christianity’s second and third centuries—a time of huge personalities, spectacular martyrdoms, and the production of some of the greatest works of Christian literature—Williams focused on the relatively unknown figure of Felicitas, an African slave-girl imprisoned in Carthage for her faith. Felicitas is most often remembered as the slave of Perpetua, her more famous mistress and fellow martyr (for more on Perpetua and Felicitas, see issues 105 and 109 of Christian History).

Yet Williams saw Felicitas’s death as one of the most significant events in the history of the church because of one single utterance. As she faced death she cried out: “Another will be in me who will suffer for me as I shall suffer for him.”

This, for Williams, epitomized what is meant by Christian co-inherence and reached deeply into the mystery of creation and redemption. The retort of the slave-girl to her jailers’ mockery told of mystical union and exchange with Christ and of the corporate community felt by so many martyrs in the early church—which led them to believe their own suffering and death had value and reconciling power in the lives of others.

These motifs appear over and over again in different guises from the beginning to the end of Williams’s creative life, in poems, essays, plays, theological studies, biographies—all products of an extraordinarily unified sensibility, a creative imagination with a strikingly original vision of the meaning of life and death, the world, and God.

Dorothy Sayers made this very point about her friend’s writings: “[Something] which in one of the novels or the plays may seem merely entertaining, romantic, or fantastical” turns out to be, underneath, “some profound and challenging verity, which in [Williams’s] theological books is submitted to the analysis of the intellect.” The opposite is true as well. Theological truths from his denser works take form and action even in those books readers are most likely to treat as entertainment: his novels.

In the last two decades of his life, Williams wrote seven novels, now the most popular of all his creations despite the fact that he personally did not regard them as his most important achievements. They have been called “supernatural thrillers,” but the description hardly does justice to their profound thought and imaginative range.

Williams always maintained that ordinary, mundane lives and actions are connected to and directed toward supernatural ends. He saw the eternal in the everyday, and in most of his novels dramatically portrayed moments when the familiar existence of the material world dissolves—revealing another kind of experience that assumes shapes of both wonder and horror. The events are dramatic, the pace is fast, the mysteries are intriguing, and the purpose is serious.

But in his last two novels, Descent Into Hell and All Hallows’ Eve, the supernatural is no longer represented by startling, theatrical interventions, but is woven much more unobtrusively into ordinary, natural life. Loving exchange and substitution now assume center stage as the means by which co-inherence is manifested and becomes real.

The English poet John Heath-Stubbs once called Williams’s last works “dark and difficult books, in which the sense of evil has become oppressive, and the characters pass across frontiers which separate the living and the dead.” It is true that they are dark and difficult and that the sense of evil is real; also that the characters pass through space and time. But they are realistic portrayals both of the human capacity for self-delusion and destruction and its capacity for acts of redemptive love.

Descent Into Hell contains one of literature’s most convincing—and terrifying—descriptions of the collapse into damnation (in the figure of the historian Lawrence Wentworth). But it also contains a sublime example of the courage of substituted love, Pauline Anstruther. Anstruther, a bewildered, rather frightened young woman, accomplishes the redemption of another by the offering of herself and in so doing finds her own release from fear and pain. Astonishingly, the one she releases is a long-dead ancestor; the force of love moves down time, and the pattern of co-inherent love knows no boundaries.

Crossing boundaries

Boundaries, their presence and absence, also form the heart of Williams’s last novel. On the first page of All Hallows’ Eve, we discover that the central character is dead—the young wife Lester Furnival, who has just been killed in an air raid on London. This audacious move gives Williams the means of exploring boundaries between the living and the dead, the natural and the supernatural, the physical and the metaphysical. In this novel two of the four central characters are living, two are dead. Three persons attain—by a process of painful, but ultimately joyful, purification—to a state of redemption; one refuses the offered grace.

Lester Furnival, like Pauline Anstruther, offers herself in an act of love and finds that in her own agony she is sustained by another—here quite explicitly by Christ. She has to learn another lesson too: the meaning of “This also is Thou; neither is this Thou.” At the border of earth and heaven, she learns that her love for her husband, Richard, deep and real though it has been, is not sufficient. The horizon of heaven places that love in a new perspective. At the close of the novel, rain falls, the quiet, cleansing rain of purgation, symbolizing both loss and gain: the repossession of the beloved “other” (Richard) in a new way. It is the paradox at the heart of the Christian Gospel (Matt. 10:39).

Such a paradox motivated the Companions of the Co-inherence to whom Williams dedicated The Descent of the Dove. He was always reluctant to set up any kind of society or order dedicated to his views, but under pressure from his friends, he agreed to do so just as the dark clouds of World War II were gathering. It was never a formally constituted society with office holders or meetings. In formulating its principles, he began by stating: “The Order has no constitution except in its members.” It consisted entirely of persons (the Companions), often unknown to one another, who discovered in his writings certain guides for living out the Christian life.

The Companions’ principles were each paired with a quotation from the Bible or Christian literature. One read: “[The Order] recommends therefore the study, on the contemplative side, of the Co-inherence of the Holy and Blessed Trinity, of the Two natures in the single person, of the Mother and Son, of the communicated Eucharist, and of the whole catholic Church. As it was said: figlia et tuo figlio [‘daughter of your son,’ a phrase from Dante about the Virgin Mary]. And on the active side, of methods of exchange, in the State, in all forms of love, and in all natural things, such as child-birth. As it was said: Bear ye one another’s burdens.”

These principles encapsulated what Williams believed: co-inherence expressed in the practice of a love that was a process of substitution and exchange; a gospel brought to life by the gifts and vision of a man for whom the poetic imagination was the surest way of laying hold on the truth. CH

By Brian Horne

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Brian Horne is chairman and librarian of the Charles Williams Society and author of Charles Williams: A Celebration.Next articles

Was the oddest Inkling the key Inkling?

It was often Williams's agitated intellect, fertile imagination, and physical energy that moved things along

Thomas HowardSo great a cloud of witnesses

Some connections and influences among the seven sages

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait and Marjorie Lamp MeadSeven sages: recommended resources

With seven influential authors and scores of books by and about them, where should one begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate