Transcending ourselves

WHEN AN AMERICAN TEENAGER explained to C. S. Lewis in a fan letter the American system of education—accumulating course credits—Lewis’s letter in response expressed amazement at measuring a student’s education by hours spent in the classroom:

What a droll idea in Florida, to give credits not for what you know but for hours spent in a classroom! Rather like judging the condition of an animal not by its weight or shape but by the amount of food that had been offered it!

He viewed education primarily in terms of what was happening in the minds and lives of the students, not in terms of what is now referred to as “seat time.” In fact, he continued by giving the teenager advice about her own creative writing endeavors: “A story about Caesar in Gaul sounds very promising.”

While Lewis’s letters are full of such gems, his fullest discussion of education comes in his essay “Our English Syllabus” in Rehabilitations (1939). There he made a three-tiered distinction between training, education, and learning. Training is vocational; it prepares the student for work. It is not intended to produce “a good man,” but simply “a good banker [or] a good electrician.”

Education has much broader goals, defined by John Milton as preparing the student “to perform justly, skillfully, and magnanimously all the offices both public and private, of peace and war.” This is a much more ambitious undertaking, trying to engender in students “good taste and good feeling,” to cultivate their aesthetic and moral sensibilities, and to fit them for public service.

Lewis thought a truly educated person should have some facility with logic and reasoning, with social behavior and civil discourse, as well as an acquaintance with the literature, both sacred and secular, that forms a culture’s legacy and its sense of community. This view of education explicitly includes a moral component.

Men and women with chests

As Lewis explained more fully in The Abolition of Man, humans cannot make sound value judgments based either upon their needs alone or their reasoning alone.

According to the classical model, humans have a head (reason) and a belly (appetites)—but in between is the chest, the seat of “magnanimity “or “emotions organized by trained habits into stable sentiments,” where fairness, generosity, and high-mindedness grow.

Lewis called these “the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral [head] and visceral [belly] man.” He called that “chest” a defining trait of humans, for by intellect humans are mere spirit and by appetites they are mere animal. A part of every education, then, should be to instruct students in the proper “stock responses,” to teach them to admire courage and selflessness, to value life, and to keep watch on their own natural penchant for dishonesty or pride.

Lewis added that a well-rounded citizen should be both “interesting and interested,” not a mere receptacle of facts, but someone with an active intellectual curiosity who can enter into discussion and make meaningful contributions.

This last trait led to what Lewis actually called learning, which he saw as far beyond education as education is beyond training. If training prepares one for work, and education prepares one to be a well-rounded human being, learning is simply a desire to know, to expand the frontiers of one’s own understanding.

For Lewis, the ultimate natural end of human life was not work, but rather “the leisured activities of thought, art, literature, [and] conversation.” He added that he called this the natural end of human life because life’s ultimate purpose must be sought in the supernatural source of our being.

Lewis considered the thirst for knowledge, like the possession of a “chest,” to be a uniquely human trait: “Man is the only amateur animal; all the others are professionals.” That is, humans can pursue learning for the mere love of knowledge, while lower animals stick to the business of survival and propagation. As Lewis whimsically concluded: “When God made the beasts dumb He saved the world from infinite boredom, for if they could speak, they would all of them, all day, talk nothing but shop.”

Though most of us use the terms education and learning interchangeably, Lewis insisted on maintaining a clear distinction. In his essay “Our English Syllabus,” he went so far as to say, “A school without pupils would cease to be a school; a college without undergraduates would be as much a college as ever, would perhaps be more a college.” (That is, faculty and alumni would still pursue scholarship for its own sake.)

A college with no students?

To those familiar with American higher education, the idea of a college without undergraduates might produce a shudder, a sign of an institution shuttered and in ruin. We associate learning for its own sake with graduate study at large research universities—usually those with government grants in the natural sciences. But Lewis insisted that for every first-year student entering college, the proper question should not be “What will do me the most good?” but rather “What do I most want to know?”

Some have argued that Lewis’s emphasis upon the pursuit of knowledge instead of job training, or even general education, is elitist or obsolete—that it simply doesn’t apply to today’s world of daunting college tuitions and dwindling career opportunities. But Lewis would counter that learning always has the important by-product of education. In seeking to expand our knowledge, we learn how to learn, developing the skills we will need both for careers and for the wider demands of family and community.

Just as those who participate in sports to win will get vigorous exercise and improved health, those who learn for the love of knowledge will gain other skills and benefits. In the same way, those who pursue such ends for their own sake may soon lose their motivation.

On the reading of old books

Another by-product of the pursuit of learning, Lewis thought, is overcoming the limits we place on ourselves.

Few students will tackle a thick book simply because they want to “broaden their minds.” But by taking interest in a variety of subjects, cultivating and satisfying intellectual curiosity, they will find that wide reading in the end has just that effect. In his essay “On the Reading of Old Books” (in God in the Dock), Lewis argued that every generation is parochial, with prejudices and blind spots that earlier generations would have deplored and later ones will expose.

Reading only contemporary books, perhaps in preparation for a career or knowledge of current events, will leave one prisoner to the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age that dominates one’s own generation. Partly because of his own wide reading in books both ancient and modern, Lewis correctly predicted that two of the most dominant thinkers of his age—Freud and Marx—would greatly recede in influence in later generations. (His critiques of both are in The Pilgrim’s Regress [1933].)

Christians should also not be reluctant to meet their fellow believers from the past: “This mistaken preference for the modern books and this shyness of the old ones is nowhere more rampant than in theology. Wherever you find a little study circle of Christian laity you can be almost certain that they are studying not St. Luke or St. Paul or St. Augustine or Thomas Aquinas or Hooker or Butler, but M. Berdyaev or M. Maritain or M. Niebuhr or Miss Sayers or even myself.”

Lewis argued that, at the very least, one should read one old book for every new one. He added that “Great Books” are usually more accessible in the original texts than in contemporary summaries or commentaries. Part of the greatness of Plato or Augustine is that they could express their seminal ideas more clearly and eloquently in their own words than can their myriads of interpreters. (The same, incidentally, is true of Lewis himself!)

Finally, apart from escaping the limited mindset of one’s own era, the pursuit of learning for its own sake contributes more broadly to what Lewis called “an enlargement of our being.” In An Experiment in Criticism, Lewis described the study of great works of literature, but his observation applies to a wide variety of texts:

We want to see with other eyes, to imagine with other imaginations, to feel with other hearts, as well as our own. . . .This process can be described either as an enlargement or as a temporary annihilation of the self. But that is an old paradox; “he that loseth his life shall save it.”

As he concludes the same book:

In reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. . . . Here, as in worship, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do. CH

By David C. Downing

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

David C. Downing is R. W. Schlosser Professor of English, Elizabethtown College (PA), and author of many books on Lewis including Looking for the King: An Inklings Novel.Next articles

So great a cloud of witnesses

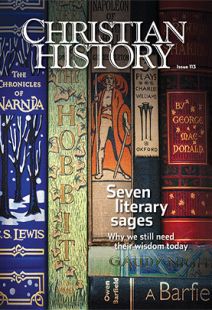

Some connections and influences among the seven sages

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait and Marjorie Lamp MeadSeven sages: recommended resources

With seven influential authors and scores of books by and about them, where should one begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center

the editorsFrancis Asbury, Did you know?

Without Francis Asbury, the American landscape would look very different

the editorsEditor's note: Francis Asbury

Methodism’s beginning in America was many things I had not expected

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate