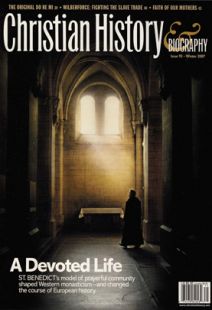

The Blessing of Benedict

Beside a lake, a monk wielded a scythe up and down in fluid arcs, clearing a thicket of thorns for a garden. He had hacked at the wild, tangled weeds most of the morning and stood briefly to wipe the stinging sweat from his eyes before returning to work. But when he swung the heavy scythe heavenward this time, its iron blade loosened without warning and flew from its wooden handle, landing with a splash far from shore. The dark water swallowed it up, along with his heart. His hand and the abandoned tool handle shielded his eyes against the sun while he searched the ripples for the blade. He began pacing beside the lake, thinking how hard tools are to replace. What will Father Benedict say?

The diligent, anxious monk-gardener was a Goth—a member of one of the pagan tribes marauding through Italy at the time. The abbot Benedict, however, had accepted this outsider into his monastery. Perhaps this Goth had once been a lowly soldier bullied by a sharp-tongued superior officer, or a servant beaten regularly with a stick. Whatever his former life, his panic at losing the tool's blade suggests that he was accustomed to being berated whenever things went wrong.

When Benedict heard of the Goth's dilemma, he sent no messenger to investigate, nor did he form a committee to look into the matter. He went himself and stood beside the Goth, who relaxed as he realized that he was not in trouble for losing a valuable tool. Benedict motioned for the scythe handle. The monk handed it over, then bent to rest his hands on his knees and studied the inexplicable movements of the abbot, who was sticking the scythe handle into the shallow water at the lake's edge. Then, out of the corner of his eye, the Goth saw something pop up through the wet surface yards from shore. His body snapped to attention as he heard a soft splash and watched the iron blade glide across the dark water to meet the handle and reattach itself.

Benedict handed the repaired scythe to him, saying, “Here. Take your tool. All is well. Go back to work, but don't be sad anymore. Stop worrying.”

The fifth-century pope Gregory the Great tells this story in his biography of St. Benedict, who is called the Father of Western Monasticism. Benedict's birth around A.D. 480 coincided with an unstable, violent period in Italy. Wave after wave of pagans invaded while the Roman Empire collapsed. Benedict responded to the anarchy of his time by founding monastic communities built on the ideal of cultivating a family spirit among the monks, on disciplined daily worship, on a balanced and non-competitive approach towards fasting and other ascetic practices, and on the dignity of manual work for rich and poor alike.

Monastery after monastery based on Benedict's Rule brought light into Italy's darkest medieval days, and because the Rule has proved remarkably adaptable in the centuries since, its notion of balancing prayer, study, and work still informs the daily lives of peace-focused Benedictine monks, nuns, and oblates around the world.

Why did Pope Gregory take time out of his busy schedule to write a life of Benedict? It allowed him to present the ideal Christ-like pastor in vivid stories. Gregory had already described this pastoral ideal in his Liber pastoralis curae, or Book of Pastoral Care, which he finished a few years before composing Benedict's story. Gregory's Pastoral Care outlines the important spiritual duties of those who serve God: They must not put their own egos before divine concerns, and they must be sensitive and responsive to the idiosyncrasies of each member of their congregation.

The story of the repaired scythe shows Benedict as a hands-on abbot whose pastoral ministry helped others achieve peace in the minutiae of ordinary life. Benedict's understanding of Christianity led him to accept and encourage people from all walks of life.

Benedict comes from the Latin word benedicere, meaning “to speak well of, to praise, to bless.” Gregory viewed Benedict's name as synonymous with his ministry. Both focus our attention on the need to listen to others in order to see their unique, God-given strengths, and then choose the right words to encourage them. Both Gregory and Benedict believed that right speech is integral to right action. Benedict's Christ-like care for others cannot be divorced from his “blessed” words of reassurance to all who knew him.

The Story and the Storyteller

Gregory's Dialogues include the only ancient account we possess of Benedict's life. Composed in 593, three years after Gregory's elevation to the papacy and roughly one generation after the traditional date of Benedict's death (547), the four books of the Dialogues describe the lives of Italian abbots and bishops as patterns of the Christian life. Gregory wanted to show a post-Roman Empire world that God was still in control despite plague, hunger, poverty, drought, pagan invasions, and division among Christians. Because our own age is scarred by similar problems, Gregory's description of Benedict's peaceful life still speaks to us all.

Gregory's work is not a biography in the modern sense of the word but a hagiography, or “saint's life.” Athanasius' Life of Saint Anthony (c. 298) set the standard by which all later works of hagiography were judged. Saints' lives featured common themes such as temptation, wilderness, hermithood, asceticism, miracles, and the nobly born protagonist who gives up his inheritance for the desert and communion with God.

Gregory never intended to write a chronological, historical account of Benedict's life, but he conscientiously based his stories on direct testimony, establishing his authority by explaining that his information came from a handful of Benedict's disciples who lived with the saint and were eyewitnesses to his miracles. What we know of Benedict, therefore, comes from an authentic medieval hagiography, and we should think of it as a genuine spiritual portrait.

Born to Privilege

Benedict was born in the tiny hill village of Nursia (now Norcia) in “Bella Umbria”—an area famous for its olive groves, vineyards, cypress woods, lavender bushes, cherry orchards, and mulberry trees. Raised in a wealthy Roman home, Benedict was taught that family is a sacred institution and that the father is its respected leader. The other guiding principle of his earliest years was obedience to a worthy communal cause. These Roman values were tested and even modified in the years to come by Benedict's growing Christian faith, but they never left him and later shaped the Rule he composed.

Around the time St. Patrick died in Ireland in 493, Benedict left his birthplace and traveled with his family and nurse some 100 miles southwest to Rome. The move from rural Nursia to sophisticated Rome, with its imperial buildings and culture, was no doubt a dramatic change for the teenage Benedict. First he studied in Rome's classical schools. Then, at 17, he gave up his boyhood tunic for a Roman toga and enrolled in a school of rhetoric, where he read and analyzed classical prose and also practiced and eventually mastered the skills of composition and public speaking. Under the tutelage of a teacher of rhetoric, Benedict must have spent hours studying the plays, speeches, letters, and philosophical epigrams of master rhetoricians like Seneca and Cicero.

Benedict soon discovered that he had little in common with his classmates, who indulged in cycles of studying and drunken partying. The poet Horace wrote that young Roman feasters ate “like wild pigs, gulping loud,” and the satirist Juvenal exposed “their unceasing ungodly lechery.”

<p>Benedict soon discovered that he had little in common with his classmates, who indulged in cycles of studying and drunken partying. The poet Horace wrote that young Roman feasters ate “like wild pigs, gulping loud,” and the satirist Juvenal exposed “their unceasing ungodly lechery.”</p>

A Counter-Cultural Life

As a new century dawned, Benedict realized that he could no longer tolerate the compromised lives of his so-called well educated companions. He quit school and left Rome, abandoning wealth, inheritance, worldly status, parents, and the potential comforts of a wife, for God. His “only desire,” Gregory said, was “to please the Lord.” We can only speculate what Benedict's family thought of this spectacular U-turn in his life.

He headed for Enfide (modern-day Affile), accompanied by his loyal old nurse. The pair walked 40 miles east into the Simbrucini Mountains, settling near a church dedicated to St. Peter, where the Christian community hosted them. Benedict worked his first miracle in Enfide when he prayed over a broken clay capisterium, a valuable wheat-winnowing kitchen sifter that his nurse had borrowed and accidentally cracked. When Benedict looked up from praying, he saw that it was restored. This miraculous event brought him unlooked-for local fame, so he left his nurse in Enfide and hiked two and a half miles north to Subiaco to live in a cave near the Anio River.

Benedict's choice of residence was perhaps his strongest rhetorical statement. Subiaco was close to the former site of a luxurious Roman pleasure villa and expensive man-made lakes constructed by the infamous first-century emperor Nero, who persecuted Christians and wasted public funds. Nero's crimes against religious freedom and his hedonism left a deep mark on Christian history.

When Benedict situated himself near the ruins of Nero's resort and its nearby aqueducts, he was silently preaching Christ-like balance and agape love in profound contrast to the worldly self-indulgence and hatred long associated with the location. Here among the shadows of imperial ego, in a narrow, ten-foot-deep cave, Benedict started his deliberate, God-focused life.

Monastic Murder Plot

Benedict's local celebrity grew. One day some monks visited him from the nearby monastery of Vicovaro, 20 miles down the Anio River. Their abbot had recently died. They had heard of Benedict's power as a holy man and came to ask if he would be their new abbot. He refused, believing them to be insincere and unwilling to live a life of spiritual discipline, but the Vicovaro monks kept badgering him. Benedict finally relented, still harboring grave doubts.

His worries proved true. The monks disliked his rules. Some were too proud to work, others were too obstinate and sullen to submit to anyone, and most were simply too lazy to do anything but what struck them as interesting at the moment. The Vicovaro brothers may have believed that their ascetic lifestyle was work enough for them.

Resentment towards their new abbot grew. In the shadowy, whisper-filled stone corridors, the brothers plotted to hide poison in the young abbot's wine cup and present it to him before supper. As usual, before he drank, Benedict blessed the cup—but it shattered when he made the sign of the cross over it. Benedict immediately realized that the wine was deadly.

With composure more frightening to the monks than any shouting could have been, Benedict reprimanded them, “May God have mercy on you. May He forgive you. Why did you try to poison me? Didn't I tell you this arrangement would never work? Your lifestyle and mine don't agree. They never will. We must go our separate ways. I won't live here any longer.”

A Rule for Monte Cassino

Benedict left the Vicovaro monks and returned to his cave in Subiaco, happy to live alone again. He loved the isolation of the wilderness and the comfort of God's uninterrupted company, but word quickly spread that the kind man of God was back. Shepherds and others made their way to Benedict's simple cave, hungry for his words.

Realizing that he must house these followers, Benedict left the solitude of the cave for good and built 12 monasteries, all neighbors to each other. Each accommodated 12 monks and a superior chosen by Benedict. He established a 13th monastery (called Monte Cassino) for those monks who would most benefit from living with and being mentored by him, and he became the abbot of all 13.

Here in these first monasteries, Benedict began to work out the details of his Rule. His experiences with the Vicovaro monks had further confirmed for him that unruly human nature required spiritual discipline. As the new father of monastic sons from widely different backgrounds, he also studied the individuals in his communities and, in a way that would later inspire Gregory, learned specific details about each. They were the high born and the peasant, the native and the foreigner, the educated and the illiterate, the young and the old—a community more diverse than today's average college dorm.

As Benedict saw relationships develop, problems crop up, and some pastoral approaches work better than others, he must have filed these experiences in his mind. During the times of lectio divina, “holy reading,” he studied the earlier Italian Rule of the Master, as well as monastic rules written by St. Basil, St. Augustine, and others. Benedict continued taking notes for many years before writing down his articulate, humane, and balanced Rule at Monte Cassino around 529. Gregory himself directs us to Benedict's Rule if we want to know more about this saint's character, for “the holy man could only teach the lifestyle that he himself lived.”

Blessing the Poor

Benedict's reputation for holiness grew, and Roman patricians began bringing their children to him for education. In response to this demand, he established schools for them. He also worked to meet the needs of the poor. Broken by war and famine, those born into Benedict's Italy grew up with little and inherited even less. Children lost fathers, women lost husbands, and all lost community. Meanwhile, Benedict watched the rich grow richer and blinder to others' needs.

One day, an emaciated man with thickly callused hands visited Benedict. He had heard that the abbot identified with the problems of ordinary men and women. “Father Benedict,” he said, “as you can see, I'm a poor farmer. The earth is unforgiving. The rains don't come, only wars and taxes. My family is hungry, and I owe my creditors 12 pieces of gold. A year's wages! I'll be thrown in jail. If I lose work, how will my family eat?”

Benedict furrowed his brow in concern. “My son, at present, I don't have even one piece of gold to give you. But come back in two days.”

As commanded, the man returned on the third day. Seeing something strangely shiny in the abbot's hands, he stammered, “What? How? All this—for my family?”

Benedict had spent the intervening days waking up before sunrise to pray for the poor man's need. On the third day, as Gregory tells it, the abbot found 13 pieces of gold on the abbey's corn chest—12 pieces for the man's debt and 1 for his family's other needs. The story ends, in my mind, with that hungry farmer running home on his skinny legs, clutching a sack filled with 13 bright, jingling coins, and thanking God for Benedict—a man of prayer who relied, not on himself, but on unending divine mercy.

Christianity for Beginners

<h3>Christianity for Beginners</h3>

Benedict knew that praising God is the best medicine for a flawed, poverty-stricken world. It requires rejecting arrogance, nurturing community, and understanding that even the oldest seeker of God is always a beginner. The epilogue of his Rule reminds us of this truth: “Whoever you may be rushing to your heavenly home, follow—with Christ's help—this little rule we've written for beginners. Only then, as God watches over you, will you ultimately reach the soaring heights of doctrine and integrity.”

Gregory would have seen this as the best lesson taught by Benedict's life: There is always more to learn. We are all always beginners. Kindness is never complete.

By Carmen Acevedo Butcher

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #93 in 2007]

Carmen Acevedo Butcher is associate professor of medieval and Renaissance literature and scholar-in-residence at Shorter College in Rome, Georgia. "The Blessing of Benedict" is an excerpt from "Man of Blessing: A Life of St. Benedit" by Carmen Acevedo Butcher (Paraclete Press ©2006, used by permission ,www.paracletepress.com).Next articles

Converting Europe

For centuries, monks were at the center of the Western missionary enterprise.

Glenn W. OlsenA Monk Who Made History

Bede gave us the single greatest source of information we have about Anglo-Saxon England.

Garry CritesIlluminating Europe

Under Charlemagne's influence, the monasteries shaped the future of Western education, trade, and even handwriting.

Thomas O. Kay with Jennifer TraftonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate