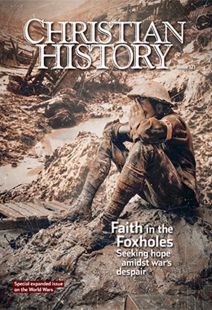

No atheists in the foxholes?

[Antwerp hospital in World War I—Wikimedia]

IN GERMAN prisoner-of-war (POW) camp Stalag 4c, a small group of imprisoned US troops gathered for an improvised Christmas Eve worship service in 1944. Since they lacked a chaplain, a young man reluctantly volunteered to lead them in prayer.

Clarence Swope, who was present at the service, recalled, “It was the most moving religious experience I ever had.” Though they prayed for the safety and comfort of their families rather than their own, Swope described leaving the gathering with an exhilarating feeling of complete faith that all would be well.

Swope’s experience raises significant questions about how other troops interacted with the Christian faith during World War II. Overall the war left a mixed religious legacy for the 16,000.000 Americans who served in the US military. Most considered themselves to be Christians both before and after the war, but few returned unchanged. For some the challenges of war deepened their Christian faith. Others, however, struggled to reconcile their experience of war with their understanding of Christian teachings. In both cases the war challenged how they understood both God and humanity.

Welcome to the army

Upon entering the military, young men and women encountered a different world. Each branch buried recruits’ individual identities beneath a new shared identity with a shared purpose—winning the war. And while before the war recruits may have defined themselves religiously as Methodist, Baptist, or Pentecostal, to the US government, these groups were all simply “Protestant.” This simplification frustrated some, but most understood the need for flexibility.

The government invested a great deal to provide religious services for soldiers and sailors for at least two reasons. First, the religious services assured civilians that their sons and daughters were being cared for.

Second, religion contributed to military effectiveness by reducing fear, drunkenness, and sexually transmitted disease. In World War II, the military employed over 12,000 chaplains from about 70 traditions. The army alone spent more than 31,000,000 dollars to build chapels stateside and overseas. In addition the government published and distributed more than 11,000,000 pocket Bibles.

These investments were heralded in promotional and training materials and in the broader press. “Even though your soldier daughter may be far from home, you need not worry about her spiritual life,” stated a Women’s Army Corps pamphlet for parents of prospective recruits. “The Army has taken special pains to see that, no matter where she goes, she is never without the comfort, guidance, and protection of the church.”

A booklet distributed to World War II army recruits also explained the usefulness of religion. “Religion is always most strengthening and helpful to people whose lives are troubled, and whose realization is greatest that forces beyond their own control may alter their lives.” Alluding to darker days ahead, it continued, “As a soldier in a savage and brutalizing war, you can find peace and comfort in religion.”

Once assigned to training camps, soldiers and sailors attempted to adapt to a new way of life, where the lack of privacy and regimented scheduling proved especially challenging. Reading a Bible on a bunk became a public display. Some evangelistically minded men used this as an opportunity to provide a silent testimony with the hope of starting conversations.

Others feared that their religion would be seen as a sign of weakness. Some troops reported being required to attend chapel during training, though requiring this was against military policy. Frank Wiswall described being marched in formation to chapel at Fort Jackson in South Carolina. Most of the men, however, kept right on marching—out the back door!

Training and work sometimes conflicted with chapel services. Military policy encouraged commanders to accommodate religious soldiers, but preparing for war remained the highest priority. Some recruits realized that they could avoid work by attending chapel. Navy cadet Keith Willison avoided chapel during training at Camp Farragut until a friend pointed out that it was better than KP (kitchen) duty. He soon became quite active in religious life and reflected that his time in the navy was spiritually transformative.

Into the unknown

Departing for overseas duty increased soldiers’ and sailors’ anxieties about the future. Most realized that they had little individual control over what would happen. As they put their worldly affairs in order, some reflected on eternal matters too. Most troop transports had a chaplain assigned who was often kept quite busy (see “Services in leaky tents,” p. 25).

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In New York the port chaplain’s office created a form letter that recorded baptisms at sea and could be sent to a local church pastor. Chaplains also led regular worship services. Marine lieutenant Jim Lucas described one service led by “a frightened young chaplain who dwelt at length on the prospect of sudden death for all of us.” Lucas concluded, “I did not find him comforting.”

As they arrived overseas, troops’ experiences with combat varied widely depending on their location and role. But all faced the prospect of danger. (In World War I, one soldier described war as “months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror.”) As the situation allowed, some men sought to reestablish familiar patterns of worship.

In the Pacific soldiers creatively constructed and outfitted chapels from available materials, such as logs, palm fronds, and lumber from shipping crates. Some used empty brass shell casings to make candleholders, vases, and Communion cups. Through craftsmanship even troops who chafed against sitting and listening in church could express themselves religiously.

“Help, Lord!”

For some facing imminent battle, faith provided a measure of comfort as the future seemed out of their control. As an infantry scout in the Pacific, Chuck Holsinger prayed and read his Bible before and during multiday patrols. He recalled praying simply “Help, Lord!” before one particularly worrisome mission. “In that moment I sensed the Lord’s presence,” he recorded in his memoir. “There was horrendous fear, but I knew that whether I lived or died, I belonged to the Lord.”

Combat correspondent Robert Sherrod witnessed a Mass held for Marines on an attack transport as they prepared to invade Tarawa. “Some five hundred men knelt in the dripping room or in the passageways leading to the room,” wrote Sherrod. “The heat and the stench from the bodies of so many sweltering men hit one in the face like a bucket of dishwater.”

Among the most terrifying battle experiences was attack by enemy artillery. Troops could do little but find a low spot and wait it out. Former infantryman Paul Casey described praying fervently as shells exploded around his hastily dug trench in a German forest. Fearful of a tree burst, against which his shallow hole would provide no protection, Casey prayed with such intensity that he actually fell asleep, alarming his buddies who thought he was dead.

On Iwo Jima Marine Pat Braden had taken a position in a shell hole when a Japanese gun started walking shells in his direction. “I assumed the prayer position, and asked the Lord to have my life spared,” he recalled. “Sweat began pouring down my face. Fear was with me.” Braden survived, and he believed that the event shaped his life.

Others were not so fortunate. Jesse Beazley, once a combat rifleman in the D-Day invasion force, commented, “I thought how good it would be if I could lay down one night without thinking somebody’s trying to kill me, if I could just go to sleep one night and sleep in peace, I could just rest.” He reflected on prayers and calls for help he heard from wounded men stranded on a battlefield in Europe. “You hear some of them that don’t know how to pray,” he recalled. “Maybe all they know is the Lord’s Prayer.” Some wounded soldiers could not be reached. “Their voice goes weaker and weaker and weaker, and it gets to be a grunt,” Beazley explained. “Then you don’t hear it no more.”

Decompression

After veterans returned home, the effects of their wartime experiences rippled through the rest of their lives. The war infused some with a new sense of purpose and thankfulness as they considered their own survival. Some desired to stay true to promises they made to God under duress (see “Christmas miracles,” pp. 56–57). Others simply wanted to live faithfully to honor those who died.

Holsinger, for example, believed that God had spared him for a purpose. He eventually returned to the Philippines as a missionary and attributed the postwar missionary boom in Asia (see “Christ and the remaking of the Orient,” pp. 47–51) to the experiences of troops in the region.

In contrast some veterans struggled to reconcile their experiences with their Christian beliefs. During war, troops debated how to best interpret the Ten Commandments’ stern proscription against killing as murder. Helen Brown reported that her brother Robert Wintermote’s interpretation resulted in guilt and nightmares long after the war. She concluded, “He didn’t need this.”

For Clarence Swope the Christmas Eve service he spent as a prisoner of war marked a high point of his faith journey—a religious experience he never found again. “I hate to admit it, but I’ve never been able to go to a church and feel that feeling,” he reflected in a 1977 interview with his son, as he explained why he was not a regular church participant. He maintained faith in a higher power but found organized religion to be largely uninspiring: “So I don’t go to church, but I think I got a reason to believe that there’s somebody somewhere that when you need him, he’s there.”

The experience of war and military service shaped the Christian faith of two wartime generations but not in easy and consistent ways. The wars forced young people to address questions about God and humanity that most of us only brush against in abstract terms. Some found deeper faith, while others floundered. In either case, war undercut easy answers. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Kevin L. Walters

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Kevin L. Walters is the director of the Roberts Center for Leadership of the Central Texas Conference of the United Methodist Church and the author of a dissertation on religion and US troops in World War II.Next articles

Support us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate