Wittgenstein’s war

THE AUSTRIAN PHILOSOPHER Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) served an eventful tour of duty on the Eastern Front in World War I. He fought bravely, won medals, wrote a philosophical masterpiece—and met God.

Wittgenstein came from an aristocratic family of Jewish ancestry in Vienna. Tragedy dogged him and his siblings: three of his four brothers committed suicide, two in the early 1900s and one as a soldier on the Eastern Front in 1918. Ludwig and his surviving brother, Paul, who lost his right arm in battle against the Russians in 1914, both considered suicide as well. Just before World War II, his sisters would escape Nazi persecution by making a financial deal with Hitler.

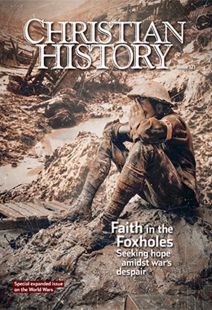

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In the early 1910s, Wittgenstein studied mathema-tics and logic at the University of Cambridge under Bertrand Russell, where, though baptized Catholic, he practiced no particular faith. When the war began, the young man enlisted in the Austrian army and was assigned to an artillery regiment. He never really fit in, however, since he was meticulous and bookish and considered the others to be “a pack of rogues.”

In late August 1914, Wit-tgenstein’s regiment moved to the front to help counteract the Russian drive to the Austrian border. While on a free day in Tarnów, Galicia, the young man found a shabby bookstore and came across a copy of Leo Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief, the novelist’s unorthodox retelling of the life of Christ—it removed the miracles and focused on the ethics of Jesus.

“How should I live?”

Wittgenstein’s secret wartime diary reveals how intensely he engaged Tolstoy’s Gospel, which he judged a “magnificent work. But it’s not what I expected.” Tolstoy’s words helped him to cope with the terrors of battle. He wrote: “I always carry Tolstoy’s ‘Statements of the Gospel’ around with me like a talisman.” (Some other solders even called him “the man with the gospels.”) And Tolstoy’s depiction of God helped the young soldier to plumb deeper understandings of existence and meaning. In September 1914 he wrote in his diary, “Again and again I say in my mind the words of Tolstoy ‘Man is powerless in the flesh but free by the Spirit.’”

Wittgenstein’s new commitments proved to be critical in October 1914 when he found himself on the ship Goplana patrolling the Vistula River under heavy Russian fire. He wrote in his diary, “I can die in an hour, I can die in two hours, I can die in a month or only in a few years. I can’t know or help or do anything about it: that’s how life is. How should I live so as to be able to die at any moment?”

As the war dragged on, Wittgenstein suffered inner torment, describing one day as “An assortment of horrible tortures. An exhausting march, one night spent coughing, a party of drunks, a society of common and stupid people. Do good and be pleased with your virtue. I’m sick and have had a bad life.” But prayer and reflection brought a measure of comfort: he concluded the entry, “God help me. I’m a poor unhappy man. God hear me and grant me your peace! Amen.”

In June 1916 Wittgenstein stood his post amid heavy shelling during Russia’s Brusilov Offensive, for which he earned the Bronze Medal of Valor; later he received another decoration, the Silver Medal for Valor, 2nd Class. Wittgenstein’s war ended in late 1918 when he was taken prisoner on the Italian front. He spent nine months as a POW and returned to his family in 1919. In 1921 his battlefield notes on logic were published as Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a book that profoundly impacted philosophy and established him as one of the twentieth-century’s greatest intellectuals.

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Jeffrey B. Webb

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Jeffrey B. Webb is professor of American history at Huntington University and the author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Christianity.Next articles

Support us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate