Meeting together for the good of the world

IT WAS THE END of the 1931 Oxford Mission, a week of revival preaching. The bespectacled archbishop of York, William Temple (1881–1944), a champion of social and economic causes, stepped to the front of the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin to lead the hymn, “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross.”

Years later, people still told how he stopped before the last stanza and asked the congregation to look at the words of the text. “Now,” he said, “if you mean [the words] with all your heart, sing them as loud as you can. If you don’t mean them at all, keep silent. If you mean them even a little and want to mean them more, sing them very softly.”

And 2,000 voices sang, very softly:

Were the whole realm of nature mine

That were an offering far too small;

Love so amazing, so divine,

Demands my soul, my life, my all.”

Temple had been on the move for Jesus ever since the World Missionary Conference of 1910 in Edinburgh, Scotland, where missionary and ecumenical leader John R. Mott tapped his shoulder and sent him off to help the Australian Christian student movement. But it was increasingly clear to him and many others that Christians from differing backgrounds needed to come together to respond to social problems.

A few years after he led that hymn, Archbishop Temple stood in front of a small group of committed Christian leaders in the living room of the president of Princeton Theological Seminary. They agreed with him: all of those presenting a contemporary Christian witness—students, missionaries, lay and clergy leaders—needed to work together. Would the dream become reality?

What shall we do?

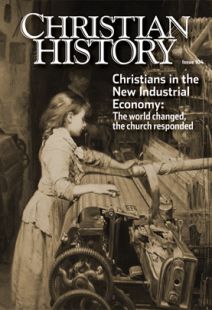

Earlier evangelical revivals had spurred cooperation across denominational lines through Bible and tract societies, mission societies, Sunday schools, and movements for social reform. But as the nineteenth century progressed, the growth of the new industrial society meant more people living in more cities, working in more mechanized industries, and suffering more problems. Many Christian churches found themselves largely unable to minister to the first truly industrial generation, being better prepared to address personal sins of private and family life than social sins of large-scale economic institutions.

This began to change as Christians came in greater contact with the poverty and social issues of the great cities. In 1833 the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul was founded in Paris to serve the needs of impoverished slum dwellers. Around the same time in Germany, the ancient Christian office of deaconess sprang up anew as devoted women sought out new roles in the field of Christian social service.

Theologian Johann Hinrich Wichern turned the attention of the German churches to what he called “Inner Mission,” bringing the spirit of foreign missions to the needs of the home country. He encouraged churches to minister to the physical and social needs of the poor along with their spiritual needs: “Love, no less than faith, is the church’s indispensable work.”

Wichern and his colleagues established homes for troubled youth, strengthened the work of schools and hospitals, and gave renewed attention to the needs of prisoners and ex-offenders. A few years later, William and Catherine Booth founded the Salvation Army in Britain (see “Breaking bread with widows and orphans,” pp. 24–28). Yet it was clear to many leaders that more was needed.

Works of charity of all nations

In 1846, even as a Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations was held in London, several hundred leaders from over 50 different Protestant Christian groups—from the British Isles, North America, and continental Europe—also gathered there. They took the name “The Evangelical Alliance” and set to work uniting Christians in a bond of mutual love and religious liberty.

At subsequent sessions in Paris, Berlin, Geneva, and Amsterdam, representatives shared their efforts with one another. They had provided educational opportunities for the poor and laboring classes, established inner-city missions near “the foulest haunts of crime,” served the needs of seamen in their ports, and protected and helped young, single women who came to cities to work in the factories, offices, and shops.

The United States founded its own Alliance branch in 1867 and sponsored an 1873 international gathering in New York. In 1886 writer and preacher Josiah Strong (1847–1916) became general secretary of that branch. He called for churches to turn their attention to America’s cities, sinking under the twin floods of young workers from the countryside and new Americans from abroad. These new urban dwellers often found themselves living in slums, cyclically unemployed, caught up in labor unrest, or battered by racial conflict. The need was urgent.

To address that need, Strong helped found the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America in 1908. It brought together many Protestant groups and sought to secure “a larger combined influence for the churches of Christ in all matters affecting the moral and social conditions of the people”—equal rights, protection of the family, abolition of child labor, limited working hours, living wages, and provision for pensions for those incapacitated by injury. It also argued that laws might be needed to achieve many of these ends.

The social question

Similar discussions were also underway in Holland. During the seventeenth century, the Netherlands had flourished, but its agriculture-based economy was now largely stagnant. It was also rapidly undergoing industrialization.

Dutch Christians formed various social organizations to address the problems of industry during the 1870s; most significant was the Nederlandsch Werkliedenverbond Patrimonium (Dutch Labor Union Inheritance) in 1876. While the Patrimonium provided a range of services to its members in troubled times, what set it apart was that both laborers and employers could become members. It thus provided an alternative model for settling disputes, emphasizing communication and dialogue rather than class struggle and strikes.

At this point Dutch Christian journalist and politician Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), who had begun his career as a pastor, stepped forward. Stimulated by Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 social encyclical Rerum Novarum (see “Brothers and Sisters of Charity,” pp. 16-20) and pushed by working-class members of the Patrimonium to take a more active stance, he helped organize the first Christian Social Congress in the Netherlands in 1891.

Kuyper confessed to not taking the “Social Question” seriously enough, allowing socialists to gain momentum. “We find ourselves fighting a rearguard action,” he lamented. He called forcefully for justice for the working class: “To mistreat the workman as a ‘piece of machinery’ is and remains a violation of his human dignity.” His words resonated internationally, as more Christians responded to the call to bring their many voices together in response to the pressing problems of the era.

Standards of the gospel

Other European Christians also met to help. The Evangelical Social Congress in Germany, begun in 1890, set up conferences on social policy and social ethics and measured current conditions against Gospel standards. British churches held a Conference on Christian Politics, Economics and Citizenship at Birmingham in 1924. But above all loomed the Life and Work Movement, shepherded into being by Archbishop Nathan Söderblom (1866–1931) of the Lutheran Church of Sweden, the first clergyman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

As a young man in 1890, Söderblom attended a Bible conference organized in the United States by Dwight Moody, where he met tireless young John Mott and was amazed at the international student movement under Mott’s leadership. Working and studying in Paris strengthened his international contacts, and when he returned to teach in Sweden, he helped spark a theological revival in the Swedish Lutheran Church.

Seeking to bring churches together after the devastation of World War I, Söderblom proposed a Universal Conference of the Church on Life and Work to be held in Stockholm in 1925. Six hundred delegates from 37 countries represented Protestant, Anglican, and Orthodox churches. The Orthodox had been making ecumenical overtures for some time; in 1920 the office of the Orthodox Ecumenical patriarchate addressed an encyclical (primarily drafted by Archbishop Germanos, later one of the first presidents of the World Council of Churches) “to all the Churches of Christ, wheresoever they be” endorsing ecumenical Christian conferences to discuss practical Christian service.

Among the topics addressed at Stockholm were urban ones: over-crowding, unemployment, and crime, which were “so grave that they cannot be solved by individual effort alone.” Economic issues provided the liveliest debate, and the conference concluded that “industry should not be based solely on the desire for individual profit, but . . . conducted for the service of the community.”

A second Life and Work Conference was held in Oxford in 1937. Stormclouds gathered, war threatened, and Hitler’s Germany posed new challenges. The writings of Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Reinhold Niebuhr for Protestants, and Nicolas Berdyaev and Georges Florovsky for the Orthodox, provoked deeper reflection from attendees on how the church had witnessed—and failed to witness—in response to the contemporary world.

The conference’s final statement confessed that Christian blindness to economic evils had been partly responsible for the rise of godless movements for social reform: “The forces of evil against which Christians have to contend are found not only in the hearts of men as individuals, but have entered into and infected the structure of society, and there also must be combatted.”

The dream he did not see

The 1937 Oxford conference and a conference on Faith and Order in Edinburgh the same year both recommended merging their efforts. Archbishop Temple was selected to chair a provisional steering committee. The dream that had motivated him for so many years was almost a reality, but Temple would not live to see it. He died in 1944.

The World Council of Churches was launched in Amsterdam in 1948, a new phase of Christian churches listening together to the Word of God and joining in common witness to the world’s needs. Like their visionary predecessors, they sought to face emerging social questions in the light of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, convinced that love so amazing, so divine, demanded all they had to give, and more. CH

By Clifford B. Anderson and Kenneth Woodrow Henke

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #104 in 2013]

Clifford B. Anderson is director of Scholarly Communications in the Jean and Alexander Heard Library at Vanderbilt University. Kenneth Woodrow Henke is curator of Special Collections, Princeton Theological Seminary Library.Next articles

Godless capitalists?

Godless capitalists? How Christian industrialists ran their businesses and used their wealth

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCommon wealth?

Communal societies influenced by Christian teachings found they could not leave economics behind

Gari-Anne PatzwaldIndustrialization: Recommended resources

There is no shortage of resources that recount how industrialization changed the world and how the church responded. Here are a few recommended by CH staff and this issue’s authors to help you navigate the landscape

the EditorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate