Listening to the African witness

CHRISTIAN HISTORY SAT DOWN separately with church historians Lamin Sanneh and Jacquelyn Winston to discuss what the stories in this issue have to teach us. We asked them about the value of the African Christian tradition in the development of world Christianity and the lessons modern Americans need to hear from these stories.

Jacquelyn Winston: As a historian of early Christianity, I believe African Christianity is one of the most important foundations of Christian faith and practice. African church fathers gave us classic formulations of the problem of evil, the philosophy-faith connection, the Trinity, and other key questions.

We often ignore the African origins of some of the most important church fathers, including Augustine, Tertullian, Cyprian, Origen, Clement of Alexandria, and Athanasius. As an ordained African-American minister, when I was confronted with a young black man who felt the Christian faith was irrelevant to his life and saw it as the religion of the oppressor, I was able to point to the rich history of African Christianity to prove that Christianity is not just “a white man’s religion.”

Nurtured in Africa

JW: From its inception, Christianity was nurtured on the African continent. The Jewish sensibilities of the first-century church were not simply Greco-Roman, they were also shaped by the religious and intellectual currents that flowed from Egypt. African Christianity is too often viewed as a brand of Christianity that has suddenly become en vogue, rather than the deep foundation of Christianity that it is. Without it, Christianity would not be the same in any substantial way.

The Middle Eastern and African origins of Christianity emphasized the communal nature of the Christian faith. The unrelenting strain of individualism at the core of American evangelicalism would benefit greatly if it embraced the corporate character of an embodied African faith.

Ultimately, we are part of a body for whom Christ died. While we may appreciate the saving work of Christ individually, it is only in our connection to the rest of the church that we can usher in the now-but-not-yet character of the Kingdom of God.

They died for their faith

JW: No one modeled this relationship more than the African fathers and mothers who were martyred for their faith in the earliest days of Christianity. Their sacrificial lifestyles, models of mutual care, and pursuit of an embodied spirituality continue to teach modern Christians.

We can easily access their truths by reading writings of the early Christian martyrs like the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas (see “The hunger games and the love feast,” pp. 6–8) and experiencing the moral struggles of Augustine’s Confessions or the spiritual struggle to be conformed to the image of Christ seen in the writings of the desert fathers and mothers (see “Become completely as fire,” pp. 15–17).

Lamin Sanneh: As we still do today, early African Christians wrestled with intersections of faith and reason, temple and synagogue, Jew and Gentile, truth and faithfulness, justice and mercy, frugality and charity, church and state, commitment and tolerance, difference and diversity, men and women, and a Christian society in a non-Christian state.

The context of the Roman Empire is similar to the context of the establishment of churches by modern empires in Africa. In both cases Christianity persisted as the religion after the empires fell.

The great tradition of philosophy and theological scholarship that distinguished Alexandria in the age of Origen and Clement (see “The Bible’s story is our story,” pp. 24–28) was swept away by the invasion of Islam in the seventh century, while elsewhere in North Africa, Christianity left only relics and fading memories as Muslim forces moved in to assert control.

Monks and manuscripts

LS: But two groups—Coptic Christians in Egypt and their Ethiopian counterparts (see “From Abba Salama to King Lalibela,” pp. 18–21)—escaped that fate. Coptic Christianity emerged from popular rural roots without the learning and refinement of Alexandria and Roman and Byzantine North Africa. Perhaps learning and refinement are not enough safeguard against decline.

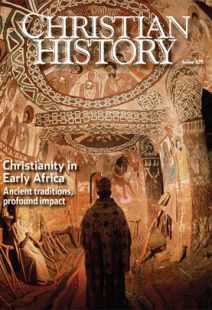

I was struck on a visit to the sixth-century monastery of Debre Doma in Ethiopia by how much the church is steeped in the soil and culture of the countryside, with a remarkable history of unbroken continuity of faith practice. There are few places in Christian history where monks, manuscripts, and monasteries have persisted that well and that long.

Think global, pray local

LS: As Christianity expanded across ethnic and national boundaries, people continued to adapt it to their circumstances. The roots of present-day Christian resurgence are still to be found in sticking close to local sources and cultures.

In his thought-provoking book, The Rise of Western Christendom, Peter Brown shows how Scripture and the devotional life helped to unify the faith and practices of Christians in the long stretch between the fall of Rome and the onset of the Middle Ages across barriers of geography, nationality, language, and communication.

Today many Christians trapped in remote rural areas as well as in deprived, marginal parts of the urban landscape have forged similar bonds of togetherness. The evidence of such indomitable faith, in the early period and today, reveals the perennial strength and force of Christianity’s message.

Africa today

LS: While Africa seems remote culturally and geographically, historically and theologically it is close to America’s self-understanding. The presence of Africans in the New World, slave and free, challenged the United States’ founders to acknowledge members of another race and culture, once remote and distant, whose destiny now was folded with America’s.

Where they failed, America’s early evangelical awakening combined with the antislavery movement. They planted churches and free settlements in sub-Saharan Africa as a bulwark against the slave trade and argued for the end of slavery and racial exploitation. That initiative opened a new chapter in the history of missions and of modern Africa.

Think back to the biblical story. When reports reached the Jerusalem church that the Spirit had brought the Gentiles to faith, the disciples exclaimed that conventional rules and taboos cannot and must not impede the Christian movement. They demanded to know how anyone could deny God was at work in new unfamiliar places (Acts 10:47). CH

By Jacquelyn Winston, Lamin Samneh, and the Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #105 in 2013]

Jacquelyn Winston is associate professor of church history and director of the undergraduate program in theology at Azusa Pacific University and an ordained minister with the Foursquare denomination. Lamin Sanneh is the D. Willis James Professor of World Christianity at Yale Divinity School and professor of history in Yale College.Next articles

The hunger games and the love feast

Perpetua’s martyrdom account gives us a window into North African spirituality

Edwin Woodruff TaitFrom Abba Salama to King Lalibela

Christian traditions in Ethiopia are among the oldest in the world

Tekletsadik BelachewThe Bible’s story is our story

How Alexandria shaped the early church’s way of reading the Bible

Joseph TriggSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate