Become Completely as Fire

A MONASTIC ASKED AN ELDER, “What good work is there that I should do?” And he said to him, “Are not all works equal? Scripture says that Abraham was hospitable, and God was with him. And Elijah loved contemplative silence, and God was with him. And David was humble, and God was with him. So whatever you see your soul desire in accordance with God, do that, and maintain interior watchfulness.” (Early monastic story)

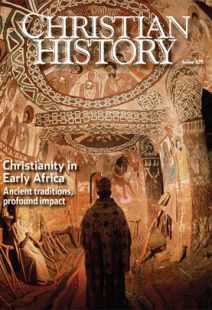

While early Christians from Syria, Palestine, and Cappadocia (in modern Turkey) made significant contributions to the monastic ideal, Egypt holds pride of place in legend and history. Ancient literature describes the monastic life as a return to Eden and a foretaste of the life to come.

Monks lived both as hermits and in community. Our most famous testimony of the hermit life comes in the Life of Anthony by Athanasius (ca. 296–373). This book by an early bishop about his ascetic friend became an ancient bestseller: high drama, exotic creatures, and the triumph of good over evil.

A pious but illiterate orphan, Anthony (ca. 250–ca. 356) inherited money and a younger sister to provide for. On his way to church one day, he thought about how the Christians in Acts sold all their possessions and gave them to the apostles to distribute to the poor. When Anthony arrived at church, the gospel reading was Matthew 19:21, in which Jesus counsels the rich young ruler to do the same.

Anthony entrusted his sister to the care of a community of virgins and took up a life of renunciation and constant prayer. He went to live among the tombs, where the Life says a multitude of demons attacked him, appearing in the form of lions, bears, serpents, scorpions, and wolves. Later he withdrew further into the desert.

After 20 years of solitude he emerged with divine equanimity, graced with powers to heal the body and console the soul. His cell became surrounded with cells of other monks, and strangers visited him seeking spiritual counsel.

Anthony exhorted Christians to prefer the love of Christ above all else: “The presence of holiness is manifest in joy and interior tranquility.” He left his beloved desert twice, once to seek martyrdom (without success) and once to combat the Arian heresy in Alexandria.

Healing Egypt

Otherwise he remained in the remote wilderness, though the Letters attributed to him show that he was well acquainted with sophisticated theology. Athanasius summed up Anthony’s life: “It was as if a physician had been given by God to Egypt.” Soon translated into Latin, the Life was as popular in the West as in the East. Hearing Anthony’s story read played a crucial role in the conversion of Augustine.

Others soon began living the contemplative life in community. Pachomius (ca. 292–346) established monastic settlements along the Nile. He drew thousands to join him and composed the first rule ever to govern the monastic life.

Original monastic motivations varied: to seek holiness, flee the law, escape from arranged marriages, or evade military conscription. But all early monastics faced common challenges to their life of prayer, introspection, manual labor, self-denial, and intimacy with Christ.

Some carried austerity to extremes, but the wiser ones realized that external practices were only means to achieve interior watchfulness and clear away distractions. Humility, sound judgment, hospitality, and love of neighbor outweighed renunciation of the world.

Along with living went teaching by word and example. The Sayings of the early Egyptian ascetics, probably gathered in the sixth century, preserves the wisdom of the earliest monastic centers in Nitria, Scetis, and Kellia (along the west side of the Nile delta).

God uses camel drivers

Larger-than-life characters leap from the pages of the Sayings: Macarius of Egypt, former camel driver and smuggler; Moses the Ethiopian, once a highwayman; Aresenius, who had lived in the lap of luxury in the imperial court; and more. Present as well are women ascetics, such as Sarah, Theodora, and Syncletica—but not in proportion to their influence. Women actually participated by the thousands in this movement.

One famous story regarding Abba (“Father”) Macarius recounts that one day he was going from Scetis to Nitria with a disciple. On the way the disciple went ahead and insulted a pagan priest, who promptly beat him up. Soon Abba Macarius met the priest and said, “Greetings! May you be well, weary one.” The shocked priest said, “What good do you see in me, that you have greeted me like this?” Macarius said, “I see you wearing yourself out, without knowing that you wear yourself out in vain.”

The priest replied, “I have been deeply touched by your greeting, and I realize that you are on the side of God. But a wicked monk met me and insulted me, and I beat him almost to death.” Then the priest fell at Macarius’s feet and said, “I will not let you go until you have made me a monk.”

The story concludes: “They made him a monk, and many pagans became Christian through him. So Abba Macarius said, ‘One evil word makes even the good evil, but one good word makes even the evil good.’”

Practical advice

Another influential monk, Evagrius Ponticus (ca. 345–399), came from Ibora (in modern Turkey) to settle in Kellia. His treatise Praktikos, a practical spiritual manual, elaborates eight demonic temptations threatening the soul. The first three tempt appetites: gluttony, sexual lust, and avarice. The second group afflicts emotions: anger, sadness, and acedia, or a restless, itching, listlessness. The third grips the whole person: vainglory (delight in empty human praise) and blasphemous pride.

The Praktikos offers insight into these temptations. Anger is “most persistent in the time for prayer, when it seizes the mind with the face of the one who has given offense.” Vainglory is “subtle and easily attacks those who are proficient in virtue.”

Evagrius urged his readers to look for patterns in tempting thoughts. Such “spiritual fire drills” would help them respond mindfully rather than be caught off guard. The goal was freedom from slavery to the passions, leading to love.

The Praktikos was the first in a trilogy describing how the spiritual adept passed from knowledge of self to knowledge of the inner meanings of Scripture and of the created world, then on to knowledge of God. Evagrius’s later books drew on Origen’s teachings (see “The Bible’s story is our story,” pp. 24–28), and for these he was declared a heretic at the Second Council of Constantinople (553).

Not all Christians shared this estimation; Syrian, Coptic, Armenian, and Georgian churches hold him in high esteem. In his influential Chapters on Prayer he wrote that “through true prayer, a monastic becomes the equal of angels, longing to see the face of the Father who is in heaven.” The goal for Evagrius was a prayer without images of God, yet full of joy.

Union with God

John Cassian (ca. 360–435) influenced both East and West. As a young man he lived among the monks of the Egyptian desert. Later, in Massilia (modern Marseilles), he composed his Institutes and Conferences.

The Institutes discusses spiritual temptations. The Conferences claims to transcribe conversations with elders of the Egyptian desert—but interpreted through Cassian’s own considerable experience and theology.

Cassian recommends anchoring the mind prayerfully in Scripture, focusing on Psalm 70:1. This prayer would triumph over temptations and prepare the soul for wordless devotion—leading to moments of fiery, illuminative ecstasy, and, beyond that, an imageless vision of Christ in his divinity.

In the end, this was the goal of all these monastics—male and female, hermit and in community. Or as the Sayings puts it:

Abba Lot went to Abba Joseph and said to him, “Abba, insofar as I can, I say my prayers, I keep my little fast, and I pray and meditate and practice contemplative silence, and insofar as I can I purify myself of distracting thoughts. Now what more shall I do?”

The elder stood up and stretched his hands to heaven, and his fingers became like ten lamps of fire, and he said to him, “If you wish, become completely as fire.” CH

By Michael Birkel

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #105 in 2013]

Michael Birkel is professor of religion at Earlham College and the author of numerous articles and books on Christian spirituality.Next articles

Early African Christianity: Did You Know?

Fascinating facts and firsts from the early African church

the EditorsEditor's note: Early African church

In this issue we walk through everything from ancient archaeological ruins to modern-day worshiping communities

Jennifer Woodruff TaitListening to the African witness

Two modern scholars reflect on Christianity in Africa, then and now

Jacquelyn Winston, Lamin Samneh, and the EditorsThe hunger games and the love feast

Perpetua’s martyrdom account gives us a window into North African spirituality

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate