Learning what no one meant to teach

“I WAS AT FOUR SCHOOLS and learnt nothing at three of them.”

Thus Lewis spoke of his education during the period 1908 to 1914, between the ages of 9 (when he ceased being homeschooled) and 15 (when he began to be privately tutored). Even if we allow for hyperbole, it was still a damning verdict on the education he received during some of his most formative years. Much has been written about Lewis’s time studying under his tutor, retired school headmaster William T. Kirkpatrick (the famed “Great Knock” of Surprised by Joy). But Lewis had much to say about his education prior to Kirkpatrick as well.

Lewis attended four schools as a boy: Wynyard School, Campbell College, Cherbourg House, and Malvern College. The worst was Wynyard, presided over by madman Robert Capron. Campbell College had Lewis on its roll for only a single term. He detested Malvern College for its emphasis on athletics and for its “fagging” system, where junior boys were little better than slaves to their seniors. Cherbourg House was the only institution that Lewis remembered warmly. Enrolled there from 1911 to 1913, he flourished under the excellent guidance of its headmaster, Arthur C. Allen. But this positive experience was the exception: the rest of Lewis’s formal schooling was evidently dismal, as opposed to the hours he spent in breaks and summers browsing his family’s well-stocked bookshelves.

Reading, writing, and solidarity

Lewis was an unusually clever boy, and clever boys are apt to kick against the constraints of large educational systems geared to the needs and reach of the average. Perhaps the three schools he condemned would not have seemed quite so dreadful to a student of more regular abilities. And perhaps we might also assume that, because Lewis’s abilities were so astonishingly advanced, he would have intellectually survived almost any pedagogical sausage-factory, however terrible.

This was not his own view, though. Of Wynyard School he wrote in Surprised by Joy: “If the school had not died, and if I had been left there two years more, it would probably have sealed my fate as a scholar for good.” Indeed, even the most brilliant mind cannot escape all the negative effects of a hopelessly bad education. For Lewis schools needed to be held to the highest standard conceivable.

Wynyard School was the polar opposite of the ideal of good schooling. It closed because of a law-suit brought against the headmaster, Robert Capron. A cruel man who flogged the boys mercilessly, he was eventually put under restraint, certified insane, and lived out his remaining days in a lunatic asylum. Lewis, though never personally the target of Capron’s brutality, struggled for years to forgive him.

But one good thing came out of Lewis’s time at Wynyard: Capron’s rule was so vile that all the boys stood solidly against it. There were no sneaks or tattle-tales. Lewis wrote later that Capron was “against his will, a teacher of honour and a bulwark of freedom.” The boys would not have so successfully understood the importance of resisting tyranny if it had been Capron’s intention to teach that lesson. Truly the lesson learned was an accidental by-product of “a wicked old man’s desire to make as much as he could out of deluded parents and to give as little as he could in return.”

Lewis wished to emphasize that teachers teach without knowing it, and one can never predict the effects with total accuracy. While we are making our schools as excellent as possible, he would argue, we also need to remember our ignorance on this point and maintain a proper humility about our role in raising the next generation. There is a modern tendency among parents, teachers, and governments to try to devise a fool-proof pedagogy, the perfect “educational machine,” as Lewis calls it in “Lilies That Fester.”

And this machine, though meant as a way of avoiding certain risks, can itself be very dangerous. It can easily squelch those whom it would instruct. Lewis wrote:

The educational machine seizes [the pupil] very early and organizes his whole life, to the exclusion of all unsuperintended solitude or leisure. The hours of unsponsored, uninspected, perhaps even forbidden, reading, the ramblings, and the “long, long thoughts” in which those of luckier generations first discovered literature and nature and themselves are a thing of the past. If a Traherne or a Wordsworth were born to-day he would be “cured” before he was twelve.

The child who engages in forbidden reading may actually be teaching himself something of great value, Lewis suggested—a lesson he had learned well from his own unsupervised reading in childhood. The burnt hand teaches best, he argued: parents and teachers must not over-protect their charges. Though it seems like a kindness to wrap a child in cotton-wool, it is in the end unwise, for the child must learn to stand on his or her own feet one day. The longer that day is needlessly delayed, the likelier it is that the child will be overwhelmed when it finally comes.

Seeking the truth

The convent schoolgirl who goes off the rails as soon as she has her liberty is all too familiar a figure. A “fugitive and cloistered virtue,” as Milton observed, is really no virtue at all. Lewis put it this way in a letter to his former pupil Dom Bede Griffiths:

The process of living seems to consist in coming to realise truths so ancient and simple that, if stated, they sound like barren platitudes. They cannot sound otherwise to those who have not had the relevant experience: that is why there is no real teaching of such truths possible and every generation starts from scratch.

By “no real teaching,” Lewis meant no direct, immediate, inescapable teaching. Since the pupil is a live and independent human being, not a machine, you cannot teach him or her exactly what you would like; students learn in their own way and in their own time. We all know that you can lead a horse to water and not make it drink; but even horses that do drink, drink as deeply as they choose and in muddy parts of the river as well as in clear.

Like seventeenth-century poet Traherne and nineteenth-century poet Wordsworth to whom he referred in “Lilies That Fester,” Lewis counted himself one of the lucky ones given space to breathe and grow in his educational upbringing. For the first nine years of his life, he was taught at home, untrammelled by the impersonal “educational machine.” And for the six years of his schooling, he had considerable independence during vacations. During these times he had free rein of his parents’ bookshelves. They contained

. . . books of all kinds reflecting every transient stage of my parents’ interests, books readable and unreadable, books suitable for a child and books most emphatically not. Nothing was forbidden me. In the seemingly endless rainy afternoons I took volume after volume from the shelves. I had always the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks into a field has of finding a new blade of grass.

Lewis was free to make his own mistakes and to bear the honorable burden of suffering their consequences, a freedom that Lewis thought could easily be curtailed in a risk-averse modern culture.

He was especially alive to the fact that freedom could be curtailed most damagingly by elites: smart people’s pretensions to wisdom are always the highest, putting too much stock in educational systems they created or endorsed. When it comes to bringing up a child, Lewis opined in one letter, “Perhaps the uneducated do it best.” The reason? “They don’t attempt to replace Providence” in shaping their destinies. Instead of thinking they can work out a plan that will infallibly secure their children’s educational futures, less ambitious parents “just carry on from day to day on ordinary principles of affection, justice, veracity, and humour.”

In a letter to Mary Willis Shelburne, who was complaining about insufficient religious education (without Shelburne’s side of the correspondence we do not know the full context), Lewis wrote this refreshingly relaxed advice:

About the lack of religious education: of course you must be grieved, but remember how much religious education has exactly the opposite effect to that which was intended, how many hard atheists come from pious homes. . . . Parents are not Providence: their bad intentions may be frustrated as their good ones. Perhaps prayers as a secret indulgence which Father disapproves may have a charm they lacked in houses where they were commanded.

Just as Capron unwittingly taught Lewis and his confreres to be “solid” and not to tell tales, so the enemies of religion might teach a child the allure of prayer.

In correspondence with his American friend Vera Gebbert, Lewis’s skepticism about the extent of human control came fully to the forefront. He talked of “the educational gamble,” admitting that “very few of us get a really good education, whether in England or America,” and expressing a surety that “if fate had sent you to one of our ‘good’ girl’s schools, you would have found quite a few holes in your stock of learning when you had finished.” And then he made the statement we began with: “I was at four schools, and learnt nothing at three of them.” He went on: “But on the other hand I was lucky in having a first class tutor after my father had given up the school experiment in despair.”

And yet this first-class tutor, William Kirkpatrick, was a confirmed and rigorous atheist! That Lewis should not have become permanently an atheist himself due to his otherwise hugely influential relationship with Kirkpatrick reinforces yet again his point: parents are not Providence, and teachers are not fate:

While we are planning the education of the future we can be rid of the illusion that we shall ever replace destiny. Make the plans as good as you can, of course. But be sure that the deep and final effect on every single [child] will be something you never envisaged and will spring from little free movements in your machine which neither your blueprint nor your working model gave any hint of. CH

By Michael Ward

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Dr. Michael Ward is senior research fellow at Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford, and professor of apologetics at Houston Baptist University, Texas. He is the author of Planet Narnia: The Seven Heavens in the Imagination of C. S. Lewis and co-editor of The Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis.Next articles

Did you know?

MacDonald’s players, Tolkien’s grave, Chesterton’s pajamas, and Lewis’s hat

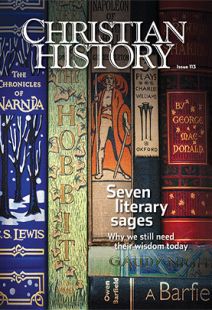

the editorsEditor's note: Seven literary sages

How much did C.S. Lewis and his friends and mentors change the society around them?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitBread of the earth and bread of heaven

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) wanted a new kind of Christian economics

Ralph C. WoodSayers “begins here” with a vision for social and intellectual change

Sayers was asked to compose a wartime message

Crystal DowningSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate