Bread of the earth and bread of heaven

MANY READERS know G. K. Chesterton as a slashing satirist, uproarious comic, master of paradoxes, deft apologist, and defender of the faith. A famed journalist in his day, he also wrote over 100 books and became one of the most notable English converts to Roman Catholicism in the twentieth century. His output included popular books like Orthodoxy, The Man Who Was Thursday, and The Ballad of the White Horse. Interestingly, C. S. Lewis attributed his return to Christian faith largely to reading Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man.

Critics often identify Chesterton as arch-conservative, even reactionary. He certainly admired things medieval and scorned things modern: woman suffrage, divorce on any grounds, contraception. His main objection to dueling, he joked, was not that it leaves someone dead, but that it settles no arguments. He was also an avowed advocate of nearly all things ancestral, describing tradition as “the democracy of the dead”—granting voice to our ancestors, the most numerous of all voters.

But don’t put Chesterton in a box marked “conservative” too quickly. He was a lifelong economic liberal, defending the poor against the rich. Long before he began to identify as a Christian, Chesterton lamented what he called the “revolution of the rich”: Henry VIII’s sixteenth-century government seizure of monastery property and estates, as well as the closing of public lands that had once served as shared grazing ground for sheep and cattle owners. But Chesterton’s anger was no antiquarian obsession. He thought market capitalism had made such exploitation ever more pernicious, especially from the nineteenth century on. He protested with a relentless barrage of denunciations:

The poor have sometimes objected to being governed badly; the rich have always objected to being governed at all. . . . It is a sufficient proof that we are not an essentially democratic state that we are always wondering what we shall do with the poor. If we were democrats, we should be wondering what the poor will do with us. . . . Among the rich you will never find a really generous man even by accident. They may give their money away, but they will never give themselves away; they are egotistic, secretive, dry as old bones. To be smart enough to get all that money you must be dull enough to want it. . . . The whole case for Christianity is that a man who is dependent upon the luxuries of life is a corrupt man, spiritually corrupt, politically corrupt, financially corrupt. There is one thing that Christ and all the Christian saints have said with a sort of savage monotony. They have said simply that to be rich is to be in peculiar danger of moral wreck.

Making good and doing good

Chesterton believed that much of modern economics, like much of modern science, envisions humans as merely animals to be controlled and manipulated like any other species. He especially opposed philosopher and political theorist Herbert Spencer’s misconstrual of Darwinism as an economic struggle for “the survival of the fittest,” a phrase that Darwin never used (see CH 107, Debating Darwin). For Chesterton this slogan enabled ruthless corporate capitalists to sanction their greed as in accord with nature, privileging the energetic and the bustling over the laggard and the straggler.

He was not altogether pleased, either, with his trips to America. He admired it as “the home of the homeless” and saluted the vigorous witness of churches and church-related colleges. Yet he was appalled by American economic competition, saying that it led to the worship of success and money as moral imperatives.

“America does vaguely feel,” he wrote in What I Saw in America (1926), that “a man making good is something analogous to a man being good or a man doing good.” Ironically, he thought, competition produced sameness rather than variety: “Where men are trying to compete with each other they are trying to copy each other.”

Chesterton was a capital-L Liberal in its original political meaning. This British political party believed that people had the right to exercise freedom and self-determination and that it was the job of good government to help them do so by setting them free.

He argued that nineteenth-century English culture largely resulted from the successful effort of the British political establishment to stave off radical social reform. Absent a revolution such as the one in France (1789), hereditary aristocrats joined the newly rich middle class to prevent the masses from gaining any real power of self-determination. (In France, by way of contrast, the masses had briefly overthrown both.) Chesterton called their victory “the cold Victorian compromise.”

Chesterton’s literary heroes, on the other hand, were morally passionate Liberals who raised the alarm to break the shameless silence about the plight of the poor and the passed over: Browning and Stevenson, Ruskin and Carlyle, and especially Dickens—these writers were unafraid to mount political pulpits and proclaim their abiding concern for the down-and-out.

Like his literary champions, Chesterton regarded the poor and destitute not as an abstract “surplus” class, but as companions encountered in the streets and lanes and shops of London. Chesterton’s friend W. R. Titterton reported that GKC “exalted cabbies and carpenters and charwomen and fishermen and farm labourers, and was on pally terms even with small shopkeepers, farmers, and country squires. He visited the slum, not slumming, but hob-nobbing; and he found everything there admirable except the slum.”

Though a devout Catholic, Chesterton proclaimed enthusiasm for the French Revolution despite its anti-Catholic crimes and horrors. He believed that at great cost it had established truths that, by cooperating with aristocrats and royalty, the Catholic Church in France had largely lost sight of. With a triple theological, political, and visual pun he stated the Christian premise undergirding democracy: “All men are equal, as all pennies are equal, because the only value in any of them is that they bear the image of the King.”

Chesterton exalted, but never romanticized, the poor as occupying an inherently blessed condition. He hoped they would make their way up into the middle class. He feared, however, that capitalists and socialists alike were keeping them in perpetual bondage, sealing them off from the freedoms and delights to be found in the life of towns and suburbs rather than of tenements and slums.

For most of his life, Chesterton assumed that enough residual Christianity remained at work in the common people that they would use their freedom wisely. The newfound liberty he advocated through his political and social writings would enable ordinary families, communities, and institutions to flourish, he thought, provided that gigantic governments and corporations did not devour them.

But gradually he discerned that, in an increasingly secularized Britain, Christianity was dying, and freedom disappearing along with it. The vision of Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor was coming to terrible fruition, in which more and more people demanded material security in exchange for their spiritual liberty (much like modern debates over the sacrifice of privacy on the Internet in the name of convenience).

Chesterton argued that both economic options are flawed. Socialists insisted that the state should protect everyone from economic and personal failure, without regard to any merit or incentive. Capitalists urged the state to promote the instinct to acquire ever more comforts and conveniences, with the result that the plutocratic few could wall themselves off from the impoverished many.

No guarantees of survival

Chesterton eventually came to believe the Liberal economic and social program had a canker at its core. While offering protections against common evils, it had difficulty defining common goods, especially when its religious basis was eroded. This political movement that had aimed to set people free from unnecessary rules and restrictions, he reluctantly admitted, would instead drain Christian virtue from the public realm and lead to a return to the brute state of nature, without a moral compass to direct and limit human desire.

Every civilization has failed, Chesterton observed, and there is no guarantee that modern Western civilization will endure simply because it is democratic. As a self-generating and self-preserving enterprise, democracy cannot provide the center to keep things from falling apart.

Yet Chesterton never panicked. Instead, he joined forces with his friend Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953), not only to find a way beyond the socialist-capitalist impasse, but also to keep his wits about him. Belloc was a writer, historian, and politician now notable mostly for his polemical essays and witty verse, including the rather macabre The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts and Cautionary Tales for Children, where we find rhymes like this one:

I shoot the hippopotamus

with bullets made of platinum,

Because if I use leaden ones

his hide is sure to flatten ‘em.

The two friends rejected capitalism as built on a profoundly anticommunal devotion to competition and thus on the desire to gouge rather than help the neighbor. They also rejected socialism as surrendering important personal and local endeavors—family, health, education—to a supposedly omnicompetent state. In both cases, the result would be what Belloc called the Servile State: voluntary slaves chained to wages and pensions and governmental controls.

Hence their revolutionary idea, which they called “distributism,” inspired largely by economic claims made in papal encyclicals Rerum Novarum (1891) and Quadragesimo Anno (1931). These encyclicals argued that the Christian virtue of justice must be understood not only as a system of reciprocity, but also as a system of distribution. Distributive justice is the notion that nothing belongs exclusively to a private individual; whatever she or he possesses is also a share of those goods belonging to everyone.

Three acres and a cow

Rather than dealing out money equally to all, like the socialists, Chesterton and Belloc wanted a system of government that would distribute modest acreages of land; newly propertied landholders would achieve personal self-respect and economic self-sufficiency in cooperation with neighbors. The two also sought to revive a modern version of the medieval guild system, so that urban laborers would own and manage the factories and companies in which they worked.

Finally, they supported the Catholic principle of subsidiarity: the idea that most important political and social matters should be negotiated as near to their source as possible. The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), Chesterton’s hilarious novel in defense of neighborhoods, takes this principle to its utmost conclusion as hero Adam Wayne fights battles in defense of his own small district of London. “Notting Hill is a nation,” declares Wayne. “Why should it condescend to become a mere Empire?”

Distributism has been ridiculed as impractical. Even Chesterton’s most ardent admirers often lament the labors he devoted to it instead of producing even more of the poetry, fiction, and cultural criticism for which he is rightly remembered. But Chesterton regarded it as his vocation to develop a distinctively Christian regard for money and property.

These things could not be left to sort themselves out, given the cultural collapse of the West—what Chesterton’s interpreter Stephen Clark called “the Laodicean mood . . . that nothing is worth dying for, but life is not worth living.” Chesterton thus came to put his trust ever more surely in the body of Christ, not the Liberal Party, as the authentic public and political alternative to the capitalist and socialist Leviathan.

He envisioned the church, for all its failings and compromises, as the world’s one truly revolutionary force. When it is faithful, he argued, it constantly pushes us toward a radical reordering of our desires, both corporal and spiritual; toward an economics capable of multiplying a handful of loaves into temporal bread for the world as well as eternal Bread of Heaven. CH

By Ralph C. Wood

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Ralph C. Wood is University Professor of Theology and Literature at Baylor University, a member of SEVEN’s editorial board, and author of The Gospel According to Tolkien and Chesterton: The Nightmare Goodness of God.Next articles

Sayers “begins here” with a vision for social and intellectual change

Sayers was asked to compose a wartime message

Crystal DowningWhy hobbits eat local

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973) and his friend Lewis shared an ideal of remaining rooted on the land of God’s good creation

Matthew DickersonMeeting Professor Tolkien

He laughed at the idea of being a classical author while still alive

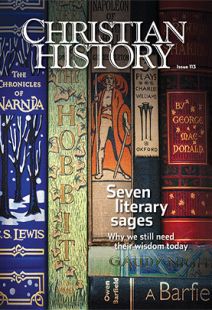

Clyde S. KilbyChristian History timeline: Biographies of the seven sages

Brief biographies of our featured authors

Matt ForsterSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate