John Wycliffe and the Dawn of the Reformation

JOHN WYCLIFFE WAS BORN around 1330 of a family which held property near Richmond and the village of Wycliffe-upon-Tees in the North Riding of Yorkshire in England. The tomb of his father may still be seen in the latter village. Almost no record of his early years exists. Actually, it is not until the last dozen years of his life when he entered into political and theological debate that we have a fuller record of him. The greater part of his life was spent in the University of Oxford.

Since little is known of his early life, we can only speculate concerning those events which influenced him. A Yorkshire man, living in a secluded area, he probably was educated by a village priest. Although anticlerical feeling existed (the clergy, one fiftieth of the population, accounted for one-third of the nation’s landed wealth), there was yet a flourishing piety at the popular level. This was sustained by the regular services of the church, plus the special dramas of nativity and miracle plays and other festivals associated with the life of Christ and His passion, and the services of vernacular carols at Christmas, Easter and Harvest.

There was also in Yorkshire in Wycliffe’s childhood an unusual interest in the writing and study of English preaching manuals, and a spirituality among the people reflected in the career and influence of Richard Rolle.

In 1342 Wycliffe’s family village and manor came under the lordship of John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster and second son of King Edward III. Because of the close ties seen later between Gaunt and Wycliffe, it is possible that the two knew one another well before Wycliffe came to national prominence. It is to be observed here that since there is disagreement as to the exact year of Wycliffe’s birth, we have chosen to follow the consensus of authorities, and thus accept the year 1330.

Working from the year 1330, we find Wycliffe leaving for Oxford in 1346, being but a teenager, yet this is the common age for entry into university. The early years of his studies were marked by the general dislocation of university life caused by the epidemics of the Black Death between 1349 and 1353. As a northern man, he probably attended Balliol College first, which school had been founded by John Balliol of Yorkshire between 1263 and 1268.

Public records also place him at Merton College in 1356 and again at Balliol as a Master prior to 1360. Not only because of the threat of epidemic, but also because of the scholastic disciplines and physical hardship, life as a student was extremely arduous experience in Wycliffe’s day. Most of the undergraduate clerks lived in residence outside the colleges and halls, there being 1500 of them in Wycliffe’s time.

In 1361 while Master of Balliol, Wycliffe received the rich college living of Fillingham in Lincolnshire, which provided income for his continued studies at Oxford.

He received his Bachelor of Divinity in 1369 and his doctorate in 1372. For a brief time he was Warden of the New Canterbury Hall but was involved in disputes there, which prompted him to leave and to go to Queen’s College where he spent the majority of his Oxford years. It was in 1370, while still engaged in his doctoral studies, that Wycliffe first put forward a debatable doctrine of the Eucharist. This was not a fully developed position, nor was it necessarily controversial, since such debate was a part of the disciplines of theological study. The receipt of the Doctorate of Divinity in 1372 marked sixteen years of incessant preparation, and to this point no open conflict with Rome had arisen.

In 1374 he was appointed rector of Lutterworth, which living he retained until his death in 1384. By 1371 he was recognized as the leading theologian and philosopher of the age at Oxford, thus second to none in Europe, for Oxford had, for a brief time, eclipsed Paris in academic leadership.

We might presume that Wycliffe had some share in the rising fortunes of Oxford as an intellectual center. Of Wycliffe it was said by one of his contemporaries, “he was second to none in the training of the schools without a rival.” Others have looked upon him as the last of the Schoolmen. He was a part of that declining system which had attempted to reconcile the dogmas of faith with the dictates of reason. Wycliffe took his stand with the Realists, as opposed to the Nominalists.

As a scholar he began, in scholastic garb, to attack what he considered to be the abuses in the Church. His attacks, when reviewed, reveal traces of ideas from several great thinkers before him. From Marsiglio of Padua came the concept that the Church should limit herself to her own province. From Occam came the idea that there was the need and the justice of an autonomous secular power, while from the Spiritual Franciscans came the exemplification of the evangelical poverty which the Gospels taught. From Grosseteste came the emphatic denunciation of pluralism. Although Bradwardine left his mark on Wycliffe (Bradwardine died in 1349), Wycliffe rejected his ultra-predestinarian views, and sought to retain some of man’s freedom. Wycliffe rejected the view that if any man sins, God Himself determines man to the act. Another man who impressed Wycliffe was Fitzralph, who had been Chancellor of Oxford before his death in 1360. He had insisted that dominion was founded in grace. This became a central idea for Wycliffe.

Out of these diverse philosophies, added to the undergirding principles of Scripture and some of the concepts of Augustine, came Wycliffe’s On Divine Dominion and On Civil Dominion. Basic to his thinking, which was to be used in the English stand against papal encroachments, were such statements as these by Wycliffe: “If through transgression a man forfeited his divine privileges, then of necessity his temporal possessions were also lost.” and “Men held whatever they had received from God as stewards, and if found faithless could justly be deprived of it.”

With the renewal of war with France in 1369, it was apparent that new monies would be needed to prosecute the conflict. Taxation led to growing anticlerical feeling in 1370, as jealous eyes surveyed the financial exemptions of the clergy. In 1371 John of Gaunt, with a secular, noble council, took power. At this point Wycliffe appeared in Parliament, and though not openly active, he encouraged the thinking that in times of necessity “all ecclesiastical lands and properties” could be taken back by the government. Such thinking was eagerly grasped at by Gaunt. In 1372, when Pope Gregory XI tried to impose a tax on the English clergy, their protest brought quick support from the royal government, and Edward III’s council forbade compliance.

There had already been an English response to the impact of foreign influence in English ecclesiastical affairs as reflected in the Statute of Provisors (1351) which forbade papal interference in elections to ecclesiastical posts and the Statutes of Praemunire (1353, 1365) which prohibited appeals to courts outside the kingdom.

An embassy was sent to Avignon to Gregory XI in 1373 asking that certain impositions against the English be set aside. In 1374 Gregory agreed to discuss the grievances, and thus a conference was arranged for at Bruges. Wycliffe was appointed as a delegate of the Crown.

In 1374, probably because of his service to the government, he received the living at Lutterworth; however, he sustained personal disappointment in 1375 in not receiving either the prebend at Lincoln or the bishopric of Worcester, which setbacks have been seized upon by many as the reason for his subsequent attacks upon the papacy.

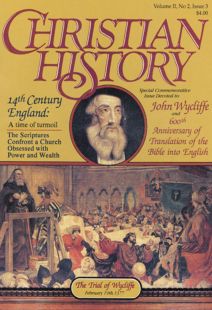

Wycliffe’s alliance with John of Gaunt eventually brought him into direct conflict with William Courtenay, the popular Bishop of London. This was occasioned by Wycliffe’s written support of certain dubious politics on the part of Gaunt. Thus, in 1377 Wycliffe was summoned to London to answer charges of heresy. He appeared at St. Paul’s accompanied by four friars from Oxford, under escort of Gaunt, the real target of these proceedings.

The following description of Wycliffe’s physical appearance there is drawn from several portraits of unquestioned originality still in existence: “ . . . a tall thin figure, covered with a long light gown of black colour, with a girdle about his body; the head, adorned with a full, flowing beard, exhibiting features keen and sharply cut; the eye clear and penetrating; the lips firmly closed in token of resolution‚Äîthe whole man wearing an aspect of lofty earnestness and replete with dignity and character. ”

The convocation had scarcely arranged itself (There was an immediate argument as to whether Wycliffe should stand or be seated), when recriminations and personal villification filled the air. Gaunt’s very manner in entering St. Paul’s had already irked the Londoners, who despised him anyway, and soon an open brawl developed. Gaunt was forced to flee for his life. This episode began to cast a new light on Wycliffe’s usefulness to the government. Still the popularity of Wycliffe temporarily kept him from further censure.

Three months after the altercation at St. Paul’s, Gregory XI issued five scathing bulls against Wycliffe. They were sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury, to the king, and to Oxford. In these bulls some eighteen errors were cited from Wycliffe’s On Civil Dominion. The church officials were rebuked for allowing such errors to be taught by the “master of errors ”. The authorities were ordered to hand Wycliffe over to Courtenay, who in turn was instructed to examine Wycliffe concerning his errors. The points of error, significantly, concerned ecclesiastical authority and organization rather than basic creedal beliefs.

Oxford refused to condemn her outstanding scholar. Instead, Wycliffe consented to a form of “housearrest ” in Black Hall in order to spare the university further punitive action by the Pope. Wycliffe refused to appear again at St. Paul’s in the prescribed thirty-day period. He did agree to appear at Lambeth, and in 1378 faced the bishops there. The government still stood by Wycliffe, whose prestige yet ranked high in the land because of the patriotic services he had rendered to the Crown. A message from the Queen Mother and the presence of friendly London citizenry were some of the factors which convinced the Commissioners of the futility of continuing the trial. They contented themselves with prohibiting Wycliffe from further exposition of his ideas.

Actually, Gregory’s bulls against Wycliffe came at an unpropitious time, for Richard II’s government was anti-papal and the national climate was not conducive to the carrying out of the intent of the bulls. Only a few days after the trial at Lambeth, Gregory XI died, and this temporarily diverted the papacy from the activities of John Wycliffe.

Wycliffe was also cited to appear at Rome, but in the hectic year of 1378, events precluded such an appearance, even had Wycliffe been so inclined to heed the summons.

Wycliffe had another major public encounter over the “Right of Sanctuary ” conflict that erupted between the church and civil authorities in 1378. Wycliffe took a strong position before Parliament defending the royal position and attacking the material and worldly privileges of the church, but legislation that ensued took little notice of his arguments as the real causes of the “Right of Sanctuary ” abuses.

By now it was becoming obvious to the politically-astute John of Gaunt, that Wycliffe’s value in the political realm had been gradually diminishing. Wycliffe’s role had been played out, and his ideas went far beyond the policies of expediency which promoted Gaunt’s patronage of the great Oxford schoolman. With 1378 we come to a milestone in Wycliffe’s career. As his political influence waned, he turned to those accomplishments for which he is best remembered. The double election in 1378 of two popes—Urban VI and Clement VII‚—served two purposes. It deflected papal attention from Wycliffe, while it also attracted Wycliffe into deeper areas of controversy and, ultimately, into what was judged as heresy. This “Great Schism ” in the church in 1378 provided a critical turning point for Wycliffe.

In the last seven years of his life, Wycliffe was increasingly withdrawn from public affairs in England. He continued to teach at Oxford until 1381 when he was banished from the university. He took up residence at his parish church in Lutterworth. Here he developed further his views dealing with three basic areas of doctrine: the Church, the Eucharist, and the Scriptures.

Wycliffe argued in Biblical terms that the true Church was composed of the “congregation of the predestined” as the Body of Christ, which Wycliffe contrasted with the visible or Church Militant.

The only Head of the Church, therefore, was Christ. From these premises he moved verbally against such practices in the Church as the selling of indulgences, and stressed the need for renewed spiritual life through the teachings of Christ in the Bible. His emphasis was on the individual’s direct relationship to God through Christ.

Wycliffe’s published views on the Eucharist, clearly delineated in 1379 and 1380 in his tracts On Apostasy and On the Eucharist, made it plain to ecclesiastical authorities that he had moved into what they considered heresy. He protested against the superstition and idolatry he saw associated with the Mass and the inordinate importance given to the priest in “making” Christ’s body.

Transubstantiation had been declared a dogma of the Church in 1215 at the Fourth Lateran Council. In pointing out the relative newness of this doctrine, Wycliffe referred to the statement of Berengarius of Tours in 1059 given to establish his orthodoxy. This statement: “The same bread and wine . . . placed before the Mass upon the alter remain after consecration both as sacrament and as the Lord’s Body.” Wycliffe interpreted this to mean that the bread remained bread even after the consecration. This view he held himself.

Wycliffe thus held to the “receptionist” view of the Eucharist, that is that the determining factor governing the presence and reception of Christ was the faith of the individual participant. He believed also the idea of remanence—that the bread and wine remain unchanged.

From 1379 on he came under heavy attack at Oxford for these views. Yet, there still existed at the university a faction loyal to Wycliffe. His position on the Eucharist was becoming that issue which would sort out his true disciples from mere respectful adherents. In 1381 the Peasant’s Revolt, though totally divorced from Wycliffe’s activity or teaching, had tended to bring more disrepute upon him. He even defended the peasants and was active in pleading their cause after the bloodshed had ceased. Again, in 1381, Wycliffe’s Confessio further amplified his views on the Mass.

Such views could no longer be countenanced, powerful as Wycliffe may have been. In 1382 the now Archbishop Courtenay summoned a special committee to Blackfriars to examine Wycliffe’s teachings. This council is also called “The Earthquake Council” because of the unusual coincidence of an earthquake at the time of its meeting, which event both Wycliffe’s followers and Courtenay’s each interpreted as a visible sign of God’s judgment upon the other.

Although some of his friends and John of Gaunt sought to dissuade Wycliffe from this clear challenge to the Church, their attempts were unsuccessful, and the Council met and took decisive action. Courtenay asked for the judgment of the Blackfriars Synod on twenty-four of Wycliffe’s conclusions. Ten of them were condemned as heretical, four of these relating to the Mass; and the rest were condemned as erroneous. Wycliffe himself was not summoned to the Synod, though some of his followers were.

The Council concluded in the apocalyptic atmosphere of the earthquake. Courtenay was quick now to seize this initiative obtained at Blackfriars. His appeal was successful in receiving temporal power to aid the bishops in restraining the power of Lollardy at Oxford. Many of the outstanding followers of Wycliffe recanted, while Wycliffe’s writings were put under ban.

For all of these external events which, both in the political and theological arenas, seemed to be spelling out an ignominious downfall for John Wycliffe, circumstances so bleak still worked in favor of his most important contribution, the translation of the Bible into the vernacular English.

This constituted the third area of doctrine in which Wycliffe clashed with the traditional teaching of the Church. It is to be observed that, influenced as he was earlier in his career by the import of Scripture, it was not until the twilight of his career that he came to a fully developed position on the authority of the Scriptures. He declared the right of every Christian to know the Bible, and that the Bible emphasized the need of every Christian to see the importance of Christ alone as the sufficient way of salvation, without the aid of pilgrimages, works and the Mass.

Wycliffe’s concentration upon the Scriptures moved him inexorably to a logical outcome—their translation into English. The clergy of his day, even had they desired to use them, had the Scriptures only in the Latin Vulgate, or occasionally the Norman French. Only fragments of the Bible could be found in English, and these scarcely accessible to the masses of people. Serving as the inspiration of the activity, Wycliffe lived to see the first complete English translation of the Bible.

This first effort immediately prompted work on a revision, which was completed after Wycliffe’s death, yet came to be identified as the “Wycliffe Bible.” Of interest it is that when John Purvey made this revision there were three main dialects extant in Middle English, Purvey chose Midland English, the dialect of London, which came to dominate the entire country, and was also used by Chaucer.

The very factors which had cut him off from an active public life were also those factors which served to bring John Wycliffe to his greatest accomplishment, the translation of the English Bible from the Vulgate.

Wycliffe spent the last two years of his life unhindered in the parish at Lutterworth. A veritable torrent of writings flowed from his pen. In 1382 he suffered the first of two strokes which left him partially paralyzed, and for this reason he was unable to answer a citation to appear in Rome. On Holy Innocents’ Day 1384, while present at the Mass, he suffered a second and severe stroke, which caused his death on December 31 of that year. Between these two strokes he had written and published his Trialogus, a systematic statement of his views, which was reprinted in 1525.

After Wycliffe’s death. his followers continued his work and carried the Scriptures to the people. But, the opposition and persecution grew more and more intense. Particularly through the efforts of Bishop Courtenay the Wycliffe movement was effectively suppressed in England. But, his writings were carried to Bohemia by students from there who had studied under Wycliffe at Oxford. His cause and teachings were taken up by John Hus and his followers, and thus were carried on more effectively on the continent than in his native land.

As a postscript to his life, it must be noted that Wycliffe died officially orthodox. In 1415 the Council of Constance burned John Hus at the stake, and also condemned John Wycliffe on 260 different counts. The Council ordered that his writings be burned and directed that his bones be exhumed and cast out of consecrated ground. Finally, in 1428, at papal command, the remains of Wycliffe were dug up, burned, and scattered into the little river Swift. Bishop Fleming, in the reign of Henry VI, founded Lincoln College for the express purpose of counteracting the doctrines which Wycliffe and his followers had promulgated. As history has revealed, Wycliffe’s bones were much more easily dispersed than his teachings, for out of a sea of controversy and angry disputation rose his greatest contribution—the English Bible.

The chronicler Fuller later observed: “They burnt his bones to ashes and cast them into the Swift, a neighboring brook running hard by. Thus the brook hath conveyed his ashes into Avon; Avon into Severn; Severn into the narrow seas; and they into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine which now is dispersed the world over.”

By Dr. Donald L. Roberts

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #3 in 1983]

Dr. Donald L Roberts is an ordained clergyman and this article is adapted from a graduate thesis on John Wycliffe which he submitted to the University of Cincinnati.Next articles

Zwingli and Luther: The Giant vs. Hercules

The Colloquy at Marburg was called in hopes of reconciling the two centers of the German Reformation—Zurich and Wittenburg, but conflict over the Lord’s Supper split their common cause.

John B. PayneA Fire That Spread Anabaptist Beginnings

Breaking with Zwingli's reform movement in Zurich, the early Anabaptists clung to their new understanding of Christian commitment, fully aware of the dangerous consequences.

Walter Klaassen, Ph.D.C.S. Lewis: A Profile of His Life

Overview of the life of Lewis including his childhood, progression from atheism to Christianity, marriage, and other major events.

Lyle W. DorsettColonial New England: An Old Order, New Awakening

A look at colonial New England and the theological giant who emerged from it.

J. Stephen Lang and Mark A. Noll J.Support us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate