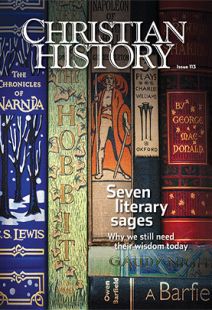

Friends, warriors, sages

Why are these seven sages still around? Why do people still read their books, talk about their ideas, and debate their influence? Christian History sat down with three experts who have written widely about these authors to probe the ways in which they still speak to us today.

Crystal Downing is Distinguished Professor of English and Film Studies at Messiah College (PA) and writes on the relationship between Christianity and culture. Colin Duriez is an author and poet living in the Lake District of England. Alister McGrath is Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at the University of Oxford and a senior research fellow at Harris Manchester College, president of the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics, and a priest in the Church of England.

CH: Why can we treat these seven authors as a coherent group?

Crystal Downing: They all proclaimed their faith at a time when Christianity was dismissed as superstitiously anti-intellectual—much more so than in our own day—and defied the modernist sensibilities that surrounded them.

For example, when T. S. Eliot became an Anglican in 1927, famous author Virginia Woolf proclaimed, “Tom Eliot may be declared dead to us from this day forward. . . . There is something obscene about a living person sitting by the fireside and believing in God.”

Similarly, in 1953 a British writer named Kathleen Nott attacked contemporary “poets and critics who have attached themselves more or less firmly to the cause of dogmatic theology,” asserting that they are “engaged in the amputation and perversion of knowledge.” Nott was especially disdainful of C. S. Lewis and Dorothy Sayers, calling them “braver and stupider than many of their orthodox literary fellows” because of their “tub-thumping” popularizing of the faith.

The book in which Nott’s statements appear, The Emperor’s Clothes, a book reprinted several times by popular demand. These seven authors put their intellectual reputations at stake to take a stand for Christ.

CH: How did they know of or influence each other?

Alister McGrath: There is no doubt that Lewis’s brilliance as a writer emerged through dialogue and debate with others—above all, J. R. R. Tolkien and Charles Williams. They sparked his imagination, challenged him to develop both the style and content of his writing, and encouraged him to keep going as a writer. Every author benefits from encouragement and constructive criticism!

Although not all of the seven sages were members of the Inklings [a group of Christian writers and thinkers centered in Oxford; see “The Inklings,” p. 25], they shared a web of relationships and associations that makes it meaningful and appropriate to speak of them as a coherent group and to tease out their mutual dependencies.

Colin Duriez: Only some of the seven authors directly interacted, of course, as between them their writings span about 130 years—from George MacDonald’s Phantastes published in 1858 to Owen Barfield’s Eager Spring, written around 1988. But the influence of their books lasted a long time and still lasts today.

MacDonald’s writings touched most of the seven, particularly Lewis, with Barfield acknowledging his “spiritual maturity” and Chesterton relishing his subtlety and simplicity—evidenced in MacDonald’s declaration that God is hard to satisfy but easy to please. G. K. Chesterton’s writings also impacted most of the “sages” who came after him. And the five later authors—Tolkien, Lewis, Sayers, Barfield, and Williams—interacted frequently. [For more on the connections between all seven sages, see our Timeline, pp. 26–27. ]

All seven writers were very distinct from each other. Considering the range of time involved, all seven are not as cohesive as are the four who belonged to the (admittedly still diverse) Inklings: Lewis, Tolkien, Williams, and Barfield.

Yet there is a living co-inherence, to borrow a useful and deeply charged term from Williams [see “The poetic vision,” pp. 42–45], among the seven. It can at least be glimpsed by seeing them within their times and recognizing some themes and preferences they had in common.

Of the seven, Lewis was the most articulate in placing himself and his friends in their historical context, though G. K. Chesterton also certainly laid bare the foibles of his age.

In Lewis’s depiction of the loyal Narnians in his book Prince Caspian, a disparate collection of talking animals and dwarfs remains true to the memory of “Old Narnia” and the distant days of the reigns of Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy in the Golden Age. The varied Inklings group were, to Lewis, similarly “Old Westerners” holding up the flame of truth in the darkness of a post-Christian world.

Lewis’s “Old West” was particularly focused on the sixteenth century—the subject of his great volume in the Oxford History of English Literature. He also drew nourishment and encouragement, like Tolkien, from the pagan world of Greece, Rome, and the northern lands. He considered them to have an unfocused prefigurement of truth, in the period before the advent of Christ.

Crystal: Sayers was profoundly influenced by Chesterton, Williams, and Lewis. She credited Chesterton with saving her faith and quoted him throughout her letters, usually writing, “As Chesterton says somewhere. . . .”

Charles Williams, however, contributed to Sayers’s greatest vocational joys. Williams reviewed with exuberant praise Sayers’s 10th detective novel, The Nine Tailors (1934), which led to multiple conversations between them. After his play Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury was performed at the 1936 Canterbury Festival, Williams recommended that Sayers be asked to write the next year’s play.

The result, The Zeal of Thy House [1937], transformed Sayers’s life [see “A Christian revolutionary?,” pp. 37–40]. In Zeal she first explored creativity as an expression of the imago Dei, the image of God in humanity. That idea informed her Begin Here [1940; see p. 18] and was elaborated more thoroughly in The Mind of the Maker [1941], which Lewis read and complimented.

Williams also contributed to the next stage of Sayers’s life: her translations and annotations of Dante. His book The Figure of Beatrice [1943] inspired her to learn medieval Italian to read the Divine Comedy in Dante’s original language. Sayers wrote Williams about her ensuing discoveries in letters so interesting that Williams shared them with Lewis.

Hence, when Williams died in 1945, Lewis asked Sayers for a contribution to Essays Presented to Charles Williams [1947]. The resulting essay was Sayers’s first publication on Dante, spearheading her translations and annotations of Inferno [Hell] and Purgatorio [Purgatory], published by Penguin in 1949 and 1955, and read attentively by Lewis. (Sayers died before completing the third volume, Paradiso [Paradise]).

Lewis also hosted a reception for Sayers following a lecture she delivered on Dante in Oxford. This supportive gesture, along with the eulogy he wrote for Sayers after she died [“A Panegyric for Dorothy L. Sayers,” published in On Stories], illustrates Lewis’s admiration for the woman he once described as “the first person of importance who ever wrote me a fan-letter.”

Already famous for her Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels when she sent her initial “fan-letter” to Lewis in 1942, Sayers recommended The Problem of Pain to others throughout her life. The Man Born to Be King [1943], the published edition of Sayers’s BBC radio plays about Jesus, profoundly impacted Lewis, who read them for his Lenten devotions every year until he died.

CH: What common themes united these Christian authors? How do these themes still speak to us today?

Colin: The seven authors all had a blend of what Lewis tried to capture in his first prose fiction, The Pilgrim’s Regress: the trio of reason, Romanticism, and Christianity. They all had remarkable abilities as innovative thinkers in their own unique ways. All turned to the making of stories: myth, parable, allegory, mystery, fantasy, or a mix of these. The appeal for all in this kind of writing lay in making other worlds which, when visited, transformed the traveler’s perception of the ordinary, everyday world.

Lewis in particular sought to undeceive his readers, challenging the narrow and inadequate modern views they might well hold of reality. Chesterton memorably spoke of hearing the horns of elfland.

A youthful Sayers also glimpsed the potency of such a renewed vision when she gave a lecture in Hull in 1916 entitled “The Way to the Other World.” She speculated about the presence of the eternal in the temporal: “One must remember,” she wrote, “that though in one sense the Other World was a definite place, yet in another the kingdom of gods was within one, Earth and fairy-land co-exist upon the same foot of ground. It was all a matter of the seeing eye. . . . The dweller in this world can become aware of the existence on a totally different plane. To go from earth to faery is like passing from this time to eternity; it is not a journey in space, but a change of mental outlook.”

MacDonald had a similar outlook threading through his fiction and other writings and directly expressed in his essays, “The Imagination: Its Functions and its Culture” [1867] and “The Fantastic Imagination” [1882]. Changes in outlook and consciousness, captured by and caused by glimpses of another world, were the very heartbeat of MacDonald, Sayers, Chesterton, and Inklings Lewis, Tolkien, Williams, and Barfield. They were concerned with the presence of the eternal in the temporal. Alister: Lewis was neither modern nor postmodern, as we now understand those terms, but rather saw himself as standing within a literary tradition that was nourished by the Christian faith and which appealed both to reason and the imagination. Lewis’s remarkable intertwining of reasoned argument, skilled deployment of images, and rich appreciation of the imaginative capacity of the human soul allowed him to speak to both modern and postmodern, affirming their strengths and subtly correcting their weaknesses.

Lewis affirmed modernity’s longing for reasonableness in matters of belief but refused to confine himself to any “glib and shallow rationalism.” He thought that truth was grasped and realized through the imagination—hence the importance of narratives and images.

And Lewis likewise, while affirming postmodernity’s realization of the importance of stories and images, insisted that truth really matters. He had no time for the easygoing relativism (“my truth” and “your truth”) that has become so characteristic of our postmodern world in recent decades.

Crystal: These friends all anticipated the ways postmodern people would subvert the rational arguments of secular humanism. How? They argued that all thinkers, from the scientist to the Sunday school teacher, understand reality according to presuppositions they must take on faith—including faith in reason itself.

Like these authors, more recent postmodern thinkers have also challenged the exaltation of reason above all that fueled modernist denunciations of Christianity. It is no coincidence that old Marxists, and “New Atheists” like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, disdain postmodernism as much as they do Lewis and Sayers (and others of the seven sages.)

CH: Why was imaginative literature a particularly potent way for the seven sages to express those themes?

Colin: All of the seven could be said to be, in their own ways, Romantics. In some sense they carried forward the Romantic movement that is associated with such English poets as Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Keats, and German poets and writers like Goethe and Novalis.

Lewis saw the great cultural divide between the “Old West” and the post-Christian era (which he also called the Age of the Machine) as falling roughly around 1830. That date, by no coincidence, marked the end point of the English undergraduate syllabus introduced by Tolkien and Lewis at Oxford in 1931. The syllabus remained in effect for over 20 years; it would be the mid-1950s before Oxford students were allowed to study more modern authors.

It could be said that the romanticism that seems to mark the seven authors is operating in a new and different era from the original Romantics like Coleridge and Wordsworth. Central to romanticism, of course, is the importance of the imagination as a reaction to rationalism. The relationship between thought and imagination was explored by the seven in many different but related ways, such as in the so-called Great War between Barfield and Lewis. There Lewis eventually conceded the importance of imagination in some forms of knowledge [see “The forgotten Inkling,” pp. 46–49].

But unlike Barfield he decided that reason was the organ of truth and imagination the organ of meaning. Some scholars have argued (Verlyn Flieger is one) that Barfield’s ideas on the imagination permanently marked Tolkien’s imaginative output, which may in fact account for some of the differences between Lewis and Tolkien.

Lewis’s view that imagination is concerned with meaning led him to pursue fiction, and fiction that often had deeply poetic prose. Eventually, he turned his energies as a Christian apologist more to imaginative writing than to the discursive, explanatory nonfiction for which he had become famous.

Lewis embraced the view, however, that myth uniquely combines meaning and truth in illuminating what would otherwise be abstraction. He felt that his two greatest efforts in retelling myth (Perelandra and Till We Have Faces) were the best of his imaginative works. Many would argue that The Chronicles of Narnia may be his greatest imaginative achievement.

All these other authors we are talking about similarly poured themselves into imaginative writing as well as discursive or scholarly writing. Most may be said to have been, to various extents, lay theologians, whose secret as popular communicators lay in their imaginative writing or speaking. MacDonald was unique among them in having theological training.

What Lewis said of Charles Williams’s romanticism after his untimely death may perhaps apply to all seven. He described Williams as a romantic theologian, which “does not mean one who is romantic about theology but one who is theological about romance, one who considers the theological implications of those experiences which are called romantic. The belief that the most serious and ecstatic experiences either of human love or of imaginative literature have such theological implications and that they can be healthy and fruitful only if the implications are diligently thought out and severely lived, is the root principle of all his works.”

Alister: Lewis came to appreciate the importance of the imagination as a child and never lost sight of this point. He saw his imagination as the means by which he was able to recognize and then break free from the “glib and shallow rationalism” of his atheist phase. Indeed, Lewis singles out certain writers—especially George Herbert and Thomas Traherne—as helping him see that imaginative writing could convey truth (in the deepest sense of the word) more effectively and faithfully than reasoned argumentation.

Lewis used imaginative literature as a way of allowing people to enter and explore new worlds and grasp their reasonableness, truthfulness, and beauty. He helped people desire truth and offered them models of how truthful living works out in practice.

The best example is Aslan himself, whom Lewis portrayed as drawing people—such as the Pevensie children—to himself on account of his nobility and magnificence. A second good example is the description of the “New Narnia” toward the end of The Last Battle, where Lewis evoked a deep sense of longing for this restored world through his careful use of imaginative language.

Crystal: Modernist empiricists, that is people focused on what can be observed scientifically, transformed the Latin term bona fide (good faith) into the definition still used today: something is bona fide, i.e. authentic, only if it is empirically verifiable.

But for medieval Christians, authentic truth was bona fide because it was something taken by faith and practiced through community. Sayers didn’t fully appreciate the bona fide of community until she began writing imaginative literature for the theater, asserting that “I recognize in the theatre all the stigmata of a real and living church.” Thanks to The Zeal of Thy House and her other religious plays that followed, Sayers experienced the interdependence of a writer, director, actor, scene designer, costume-maker, lighting technician, etc., all contributing to and learning from each other.

Theater thus echoes St. Paul’s most extended metaphor: the church as one body with many members, each with an important role to play. But, more important, the imaginative literature that the theatrical body performed—whether on stage or on the radio—was what powerfully affected many of Sayers’s contemporaries. She received scores of letters from people telling her that for the first time in their lives, thanks to her plays, Christ and/or Christian doctrine made sense to them.

Sayers, then, would encourage Christians to engage theater as a means to get past watchful dragons. I particularly think she would be delighted with the imaginative work of my colleague Ron Reed, who is currently writing a play exploring the complexities of the friendship between Tolkien and Lewis—a play that includes parts for Williams, Sayers, Joy Davidman, and Inklings Warren Lewis (C. S. Lewis’s brother), Hugo Dyson, and Roy Campbell. Even today, the interaction between these authors still fascinates—and their truths still compel. CH

By the editors with Alister McGrath, Chrystal Downing, Colin Duriez

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Next articles

The storyteller

The stories of George MacDonald (1824-1905) showed goodness and holiness to Lewis and Chesterton—and show those same things to us

Kirstin Jeffrey JohnsonWhat C. S. Lewis learned from his “master”

Lewis’s recommendation to seekers: read George MacDonald

Kirstin Jeffrey JohnsonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate