More great awakeners

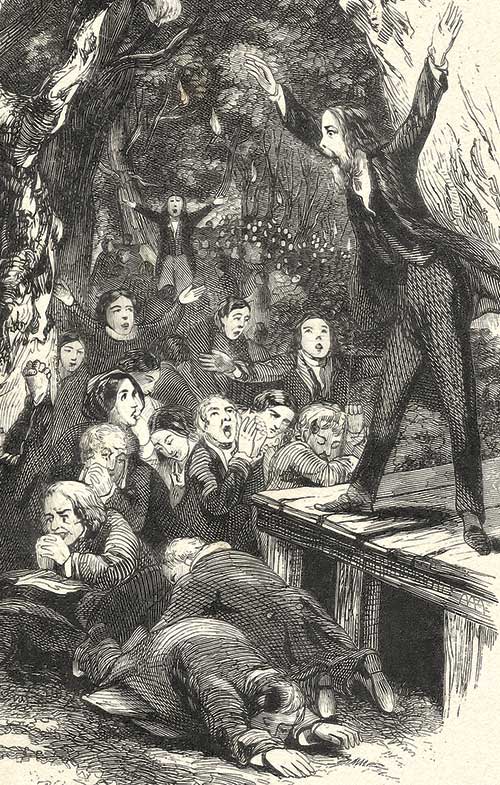

[Samuel G. Goodrich, The Jerking Exercise from Recollections of a Lifetime, 1856, engraving—Public domain, University of Pittsburgh Library]

SOLOMON STODDARD (1643–1729), PURITAN REVIVALIST

Born into an aristocratic New England family in Boston, Solomon Stoddard graduated from Harvard University in 1662. He served as the university’s first librarian and also spent time as a Congregationalist minister in Bermuda.

The town of Northampton, Massachusetts, which was settled in 1654, called Eleazar Mather to be their minister in 1659. Within 10 years, Mather was dead, leaving behind a 25-year-old widow, Esther, and three children. In that year, 1669, Northampton Church called on Solomon Stoddard to preach his first sermon in Northampton. Events moved quickly, and, in 1670, Stoddard became both Northampton Church’s minister and Esther Mather’s new husband.

Stoddard’s position in Northampton proved to be influential throughout New England. As the first generation of Puritans were passing away, their children were not as interested in maintaining the strict bounds of church membership their parents held—membership that also determined colonial citizenship. Stoddard became instrumental for his proposal of the Half-Way Covenant. Previously, in the Puritan tradition, to become a member of the church, one must have a “conversion experience.” But Stoddard allowed people to receive Communion and baptize their children without the official conversion restrictions, a move not popular with some Puritan leaders, but helpful in keeping people in the pews.

This change in membership qualifications, however, did not affect Stoddard’s desire for New Englanders to experience true Christian conversion. Between 1679 and 1719, he preached through five revivals, when many people, especially the young, turned to salvation through Christ. Stoddard taught one student in particular his methods of preaching to produce revivals: Jonathan Edwards, his grandson and the primary orator during the First Great Awakening.

ALPHONSUS LIGUORI (1696–1787), FOUNDER OF THE REDEMPTORISTS

Alphonsus Liguori was born near Naples, Italy, and graduated with two legal doctorates at age 16. Liguori found success as a lawyer, not losing a case until he was 27, at which point he heard the Lord say, “Leave the world, and give yourself to Me.” He became a priest at 30, and he was beloved for his profound but accessible sermons.

Almost six years following his ordination, Liguori founded the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer. Also known as the Redemptorists, the group of priests was charged to serve, labor among, and preach to the poor in both urban and rural areas. The Redemptorists also felt called to combat Jansenism in Catholic circles. In contrast to the extreme moral rigorism that he felt Jansenists required of their adherents, Liguori stressed grace, believing that “the penitents should be treated as souls to be saved rather than as criminals to be punished.”

Against Liguori’s desires, Pope Clement XIII named him bishop of Sant’ Agata del Goti near Naples in 1762. Liguori made the best of the situation by reforming the diocese from the top down. And though political mishandling of the Redemptorists toward the end of his life deeply discouraged him, his congregation survived; today, Redemptorists minister in 100 countries. Pope Gregory XVI canonized Liguori in 1839.

MARY BOSANQUET (1739–1815), COMPASSIONATE METHODIST MINISTER

Born in England into a wealthy Anglican family with Huguenot ancestry, Mary Bosanquet became intrigued by Methodism and converted around 1757. This created family friction, especially when she refused marriage to a wealthy young man of her parents’ choosing.

Deciding to use her family’s wealth to glorify God and help others, Bosanquet and her friend Sarah Ryan modified her family’s large home, The Cedars, into an orphanage, hospital, and halfway house for needy people. Bosanquet led Methodist services there so the orphans would have a robust religious education. In 1768 she moved the orphanage to the country and renamed it Cross Hall.

In 1771 Bosanquet defended her preaching as a woman to Methodist founder John Wesley. She felt God had given her an “extra-ordinary call.” She argued that by preaching, she was not holding authority over men, but simply calling sinners to repent as well as describing Jesus’s work in her own life. Wesley agreed, establishing a precedent.

Bosanquet served at Cross Hall until her marriage, finding homes or work for all the orphans before closing the orphanage in 1782. Together, Bosanquet and her husband, John Fletcher, started a Methodist ministry in Madeley, England, where both preached, cared for the sick, and taught Methodist classes. John Fletcher died in 1785. Though Wesley tried to convince Mary to minister in London now that she was a widow, she continued to preach, teach, and serve in Madeley, all while living in the vicarage. She preached five times a week until the age of 75 and died in 1815.

JEREMIAH MINTER (1766–1829), FIERY HOLINESS PREACHER

Jeremiah Minter was born in 1766 in Virginia. As a young man, Minter was instantly attracted to Methodism because of its strict rules on holiness. He was ordained as a preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church around the age of 21. By 1789 he was appointed deacon, and the following year he became an elder. This was a prominent position, especially for such a young man, as Methodists had only 66 other elders in the entire country.

Around this time Minter was assigned to provide spiritual care for a district in Virginia. He came into contact with devout Methodist and wife of a plantation owner, Sarah Jones. Minter was a preacher of the “fire and brimstone” persuasion, and he frequently checked in on the believers in his district. Thus he would often travel to Jones’s plantation, and they shared a deep relationship through frequent letters.

Gossips speculated that Minter and Jones had had a sexual relationship, and though those charges were unproven, it caused Minter enough distress to allegedly choose the life of a eunuch. Minter soon encountered trouble within the Methodist leadership as his condition became widely known. Francis Asbury wrote in his journal, “Poor Minter’s case has given occasion for sinners and for the world to laugh, and talk, and write.” Minter was sent to preach in the West Indies, and when he returned to America six months later, he refused to repent. He was thus demoted to a local preacher, and he went on to write a scathing report accusing Asbury of sorcery.

Sarah Jones died in 1794, and in a twist of events, Asbury preached at her funeral. Minter went on to publish Jones’s autobiography in 1799, including some 150 pages of her letters, including her intimate correspondence to him.

LORENZO DOW (1777–1834), ECCENTRIC PRIMITIVE METHODIST

Born in Connecticut, Lorenzo Dow became a Methodist in his youth. As a teenager he attempted to become a preacher but was rejected by Methodist leadership. But in 1798 he was invited to become a probationary Methodist circuit preacher in New York, which also took him to Vermont and Massachusetts. After Dow’s missionary trip to preach to Catholics in Ireland, the Methodist leadership separated itself from his ministry. In 1799, 1805, and 1818, he traveled to Ireland and England, introducing revival camp meetings to the people. His work in England prompted the creation of the Primitive Methodist Church, a Methodist denomination focused on holiness.

Dow was an eccentric person and preacher. He was unkempt, with a long, unwashed beard. He preached boldly and without self-consciousness, often crying, cajoling, shouting, pacing, joking, and begging. Though unable to officially represent the Methodist Episcopal Church, he preached a Methodist message while denouncing Calvinism, Roman Catholicism, deism, and anything else he believed was counter to Jesus Christ’s message of forgiveness and redemption. He most often traveled on foot, sometimes joined by his wife, Peggy.

He was an avowed abolitionist, and thus he often met violent detractors in the South. But he was not deterred, recalling in his autobiography when God first called him to preach:

“Arise and go, for I have sent you.” I said, “Send by whom thou wilt send, only not for me, for I am an ignorant, illiterate youth; not qualified for the important task”—The reply was—”What God hath cleansed, call not thou common.”

Having traveled the entirety of the then United States, Dow died at age 56 in Washington, DC. His 1834 obituary declared,

He had been a public preacher for more than 30 years, and it is probable that more persons have heard the Gospel from his lips, than from those of any other individual since the days of Whitefield.

PETER CARTWRIGHT (1785–1872), GOD’S PLOWMAN

Born in Virginia, Peter Cartwright grew up in Kentucky after his father, a Revolutionary War veteran, moved their family in 1790. There Cartwright converted to Methodism as a teenager during a revival camp meeting. He described his conversion in his autobiography: “And though I have been since then, in many instances, unfaithful, yet I have never, for one moment, doubted that the Lord did, then and there, forgive my sins and give me religion.” Within a year Cartwright began a preaching circuit in the wild, largely unchurched West. He was ordained by Francis Asbury and William McKendree in 1806.

Calling himself God’s Plowman, Cartwright had great stamina as a preacher, covering 400 miles within his district. But as he traveled, he saw the evils of slavery, so he chose to move to free-soil Illinois in 1824. He continued to preach for more than 50 years throughout Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, seeing thousands of converts. He also traveled with a library: the Bible, a hymn book, and the Methodist Book of Discipline. A man of the frontier, Cartwright preached boldly, calling all sinners to repentance.

Cartwright opposed slavery but feared that using political power to end the scourge would permanently divide the country; instead he preferred appealing to people’s morality. When Cartwright served two terms in the Illinois State legislature as a Democrat, he continued to appeal to common morality over political maneuvering to end slavery. Eventually he lost a bid for a seat in Congress to 37-year-old Abraham Lincoln in 1846. After a long and full life as a father, husband, circuit preacher, chaplain in the War of 1812, college cofounder, and politician, Cartwright died in 1872.

HENRY WARD BEECHER (1813–1887), ABOLITIONIST AND ORATOR

Born in Connecticut, Henry Ward Beecher was the eighth of 13 children of the renowned Rev. Lyman Beecher, a preacher during the Second Great Awakening. Many of Beecher’s siblings went on to profoundly impact society through their advocacy, including his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Beecher was an unimpressive student, but when he began attending Amherst College, he displayed great talent as an orator and leader. Following graduation from Amherst, he attended Lane Theological Seminary in Ohio, graduating in 1837. He then married Eunice Bullard and became the minister of Second Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis in 1839. His informal preaching style captivated his congregation. Beecher returned to the East Coast as minister at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York. Always against slavery, Beecher became more adamant in his abolitionist stance.

Though raised in a strict Calvinist home, Beecher took a different tack than his father, stressing God’s love over discipline. He popularized a gentler and more socially conscious Christianity, campaigning not just for abolitionism, but also for women’s suffrage, evolution’s compatibility with Scripture, temperance, and the South’s quick reconstruction following the Civil War.

Beecher was often accused of being a womanizer, and in 1875 a sensationalized trial began regarding his alleged affair with the wife of a close friend. The jury was unable to reach a verdict, but Plymouth Church exonerated him the following year. He died in 1887. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a copy editor and writer. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

Awakenings: Recommended resources

Read more about the Great Awakenings and the renewal movements that preceded and followed them in these resources recommended by our authors and the CH team.

the editorsMore than revival

The Second Great Awakening Christianized a nation from East to West

Thomas S. KiddSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate