Lightning strikes

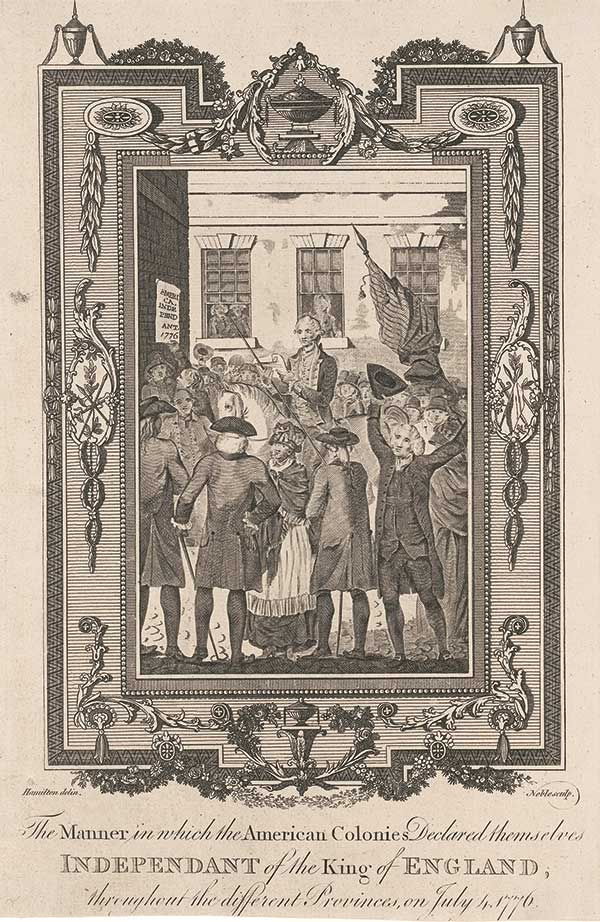

[The manner in which the American colonies declared themselves independant [sic] of the King of England, throughout the different provinces, on July 4, 1776, c.1883, engraving—Public domain, Library of Congress]

Northampton, Massachusetts, and its distinguished pastor Jonathan Edwards seemed unlikely candidates for a major revival. Nor did the spiritually moribund decades after the fires of the Pilgrims, Puritans, and William Penn portend a religious awakening. By the eighteenth century’s opening, enthusiasm for spreading the gospel throughout the New World had become smoke and embers. Most churches were going through the motions of worship and congregational life, some led by spiritually lifeless pastors who held to a form of religion while denying its power. God, however, seemed to have other ideas. According to theologian Richard Niebuhr, America’s “national conversion” was about to commence at just this juncture, in some improbable places, led by uncommon men.

Revival fire

The first lightning strike occurred in Northampton under the leadership of the deeply cerebral Edwards, whose sermon delivery would surely fail a contemporary public speaking course. Although he preached deeply and thoughtfully about the individual’s need for salvation, he spoke in a dry, monotonous tone and failed to make eye contact with his parishioners. Some historians have speculated God may have chosen to begin this revival at Northampton and through Edwards so no one could suggest that what happened there was because of a charismatic personality or the particular righteousness of the town.

Toward the end of December 1734, after Edwards began a sermon series about justification by faith alone, he started noticing startling changes in his congregation. He recorded,

the Spirit of God began extraordinarily to . . . work amongst us. There were, very suddenly, one after another, five or six persons who were, to all appearance, savingly converted, and some of them wrought upon in a very remarkable manner.

He was especially taken by a young woman’s example, “one of the greatest company-keepers in the whole town,” who came to her pastor to tell of her broken, repentant, and newly sanctified heart. Soon many others followed in her footsteps. Edwards reported,

This seems to have been a very extraordinary dispensation of Providence: God has, in many respects, gone out of, and much beyond his usual and ordinary way.

As a result of individual conversions, Edwards cited the “glorious alteration” that took place in Northampton so that by the following summer,

the town seemed to be full of the presence of God. It never was so full of love, nor so full of joy . . . there were remarkable tokens of God’s presence in almost every house.

Prior to this revival, an average of 30 people a year came to faith in Christ, but now far more were making professions of faith on a weekly basis. Most of them, according to Edwards, were “awakened with a sense of their miserable condition” before a holy and just God and “the danger they are in of perishing eternally.”

New Lights

The revival that claimed Northampton struck other colonies as well. In New Jersey a Dutch Reformed pastor, Theodore Frelinghuysen (c. 1691–c. 1747), had been preaching about heartfelt conversion since his arrival in America in 1720, when he was appalled by the spiritual apathy he encountered. He went on to influence Scottish-born pastor William Tennent, who, with his son Gilbert (1703– 1764), preached the necessity of salvation by faith. A self-described “old grey-headed disciple and soldier of Jesus Christ,” Tennent proved to be a key figure in what became known as the First Great Awakening.

Additionally Presbyterian ministers Samuel Davies (1723–1761), who labored in Virginia, and David Brainerd (1718–1747), who ministered among Native Americans in New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, witnessed spiritual fervor. Brainerd wrote of being in open awe of the power of God that fell on one village after another as he preached. Native Americans changed so dramatically that skeptical Whites went to the meetings to mock, only to be delivered themselves!

These lightning rod preachers came to be known as “New Lights.” They clashed with the old guard ministers, whom these revivalists preachers critiqued as presiding over prestigious but spiritually dead congregations. The “Old Lights,” however, responded with their own criticism, ridiculing the New Lights’ unconventional ways. They asked, for example, what business William Tennent had training mere farm boys to preach the gospel and referred contemptuously to the Pennsylvania school Tennent founded to raise up ministers as a “log college.” However, the pastors he trained soon became revivalists who took the gospel to Virginia, North Carolina, and as far west as Ohio—his humble school eventually providing the foundation for Princeton University.

William’s son Gilbert didn’t exactly make friends among the establishment clergy by preaching against “the danger of an unconverted ministry.” He said,

As a faithful ministry is a great ornament, blessing, and comfort to the church of God (even the feet of such messengers are beautiful), so, on the contrary, an ungodly ministry is a great curse and judgement. These caterpillars labor to devour every green thing.

This and other unfavorable comparisons led to deeper divisions between the Old Lights and the New Lights, as proven by the schism that buffeted the Presbyterian Church for nearly two decades afterward.

Lightening across the pond

While God’s Spirit moved among localized pastors to awaken colonial America, a prophet came from England to fan those fires into a spiritual conflagration. Like Jonathan Edwards, the Anglican evangelist George Whitefield also seemed an unlikely person to spread revival throughout the colonies, but for a different set of reasons. Whitefield had spent his youth play-acting in school and helping run the family inn. During his years at Oxford University’s Pembroke College, he became friends with two brothers, Charles and John Wesley. The Wesleys were earnest young men who sought a deeper experience of God than was usually spoken of by that day’s ordained clergy.

Although Whitefield strove, as Martin Luther famously had, to feel right with God, a sense of spiritual peace about his eternal state eluded him. The breakthrough came when he read an obscure book, The Life of God in the Soul of Man (1677), by Scotsman Henry Scougal (1650–1678), which encouraged people to cease striving and allow the Spirit of God to dwell within them. Thoroughly excited by this discovery, Whitefield set out to tell his fellow Englishmen that salvation is God’s gift, not something they could earn by good works.

This message proved to be difficult to sell in a country where people attended church out of social obligation and the pastors’ sermons were thought to be as dry as the dust Whitefield had once swept from his family’s inn. In contrast he preached in a fresh, bold way, calling upon his flair for the dramatic to beckon people from their slumber toward wide-awake salvation. His style mortified the staid English: Whitefield often shouted, danced, sometimes cried, and frequently flailed his arms while speaking of people living hopelessly apart from Christ. Fellow pastors told him to tone it down, but the hope Christ offered to lost people for this life and the next kept him on the move, in more ways than one.

Eighteenth-century celebrity

In 1738 Whitefield felt compelled by God to go to the American colonies because he had heard its churches were as benumbed as England’s. Initially the Americans weren’t sure what to make of his theatrics, but they weren’t as quick as the English clergy to write him off as an “enthusiast.” He used his powerful voice and gestures to speak boldly about sin and salvation and heaven and hell, as he called people to exchange their head knowledge of Christ for a heartfelt personal commitment.

People came out to hear him speak in the open air by the thousands. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison observed, “to people who had not heard this clearly explained before, it was like a lightning shock to the heart.”

Whitefield preached up and down the eastern seaboard, drawing enormous crowds, comparable in size to those who follow rock stars today. When he took his message to Philadelphia, he inspired the curiosity of a young printer named Benjamin Franklin (see p. 20) who observed:

The multitudes of all sects and denominations that attended his sermons were enormous, and it was a matter of speculation to me, who was one of the number, to observe the extraordinary influence of his oratory upon his hearers, and how much they admired and respected him notwithstanding his common abuse of them by assuring them that they were naturally half beasts and half devils.

Franklin delighted in the transformation he witnessed in Philadelphia’s civic life. He wrote,

From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street.

Similar transformations occurred wherever Whitefield preached.

A new national identity

As a result of the First Great Awakening, church attendance boomed throughout the colonies. In addition the moral tone of the day improved vastly in many places. Mission-mindedness and public service increased, especially in ministries among Native Americans and slaves. New institutions of higher learning were created to prepare young men for pastoral work, including Princeton, Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth.

One of the awakening’s greatest legacies was that this outpouring of God’s Spirit led people who once regarded themselves in a regional framework to identify as “Americans.” As Whitefield preached over 18,000 times between 1736 and 1770, he helped solidify this national consciousness as new converts found a commonality with other believers in Christ no matter their location.

The new revivalism also fostered a great leveling of social strata. Barriers broke down between people of various denominations, races, economic conditions, and sexes. Those touched by the Holy Spirit considered themselves on equal footing before God’s throne of grace, both as sinners as well as redeemed saints. All were one in Christ Jesus.

Likewise there came a more vertical shift in allegiances. Christians believed first and foremost they owed their fidelity to King Jesus, not King George, whom they regarded with increasing suspicion and hostility as he used the colonies to further and enrich his own purposes. He was tone deaf to the belief that Americans had a God-given destiny to promote the gospel of freedom on a continent set apart for a new way of living. As the king continued to encroach upon the rights of American colonists, their impulse quickened toward breaking away from his determined grip. Many political leaders and revivalist pastors pushed for independence, believing if they failed to obey Almighty God, they would be accountable to him in the final judgment, a prospect much more terrifying than war with Britain and its superior military might.

In the end the spiritual awakening that had struck the colonies prepared its people for what came next: the rigors of a war with England.

And the lightning strikes came with thunder, resounding both politically and spiritually in the newborn nation. CH

By Rebecca Price Janney

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Rebecca Price Janney is a historian and the author of 26 books, including her award-winning historical fiction Easton Series. She is also a member of the CHI board.Next articles

Christian History timeline: awakenings, renewals, revivals

Revival movements of the early and modern eras

the editorsWords that bring the dead to life

Issue advisor Michael McClymond walks CH through revival preaching

Michael McClymondSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate