“A church rightly reformed . . .”

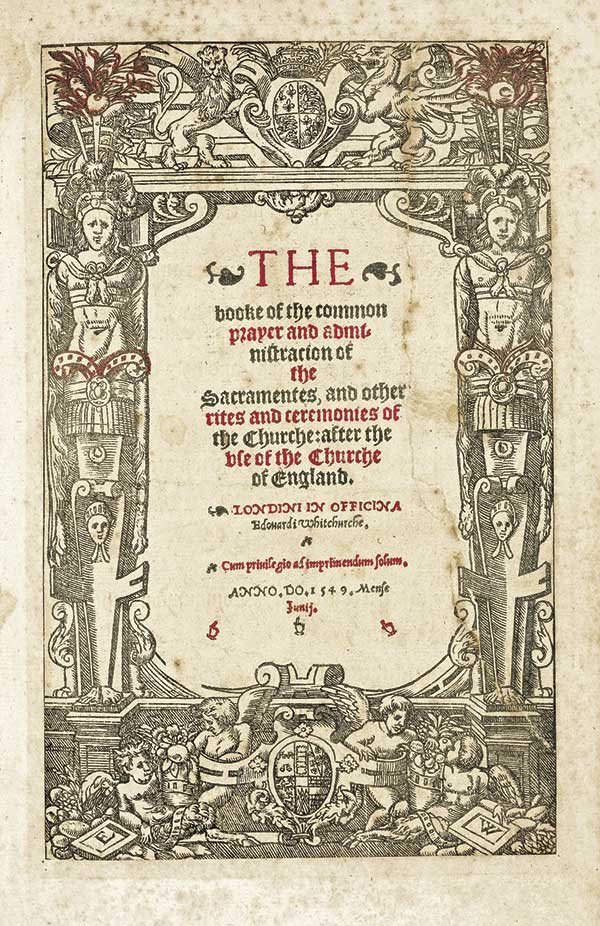

[Above: Thomas Cranmer, The Book of Common Prayer, 1549—British Library / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Two travelers met on the road leading out of London and fell into easy conversation. A question came from the first, Zelotes: “Do you have a preacher in your town?” His companion, Atheos, bragged about his minister—“the best priest in the country”—and rattled off his virtues. His curate was gentle and didn’t chide harshly if parishioners went to the alehouse. He was also known to join in bowling or cards as the occasion allowed. Zelotes, unimpressed, judged the priest more fit to care for swine than the “precious flock of Christ.”

Atheos wised up to his companion’s true identity. “I perceive you are one of those curious and precise fellows which will allow no recreation. You would have them sit moping always at their books. I like that not.” Sensing in Zelotes’s condemnations hypocrisy, he added: “You precise Puritans find fault where there is none. You condemn men for every trifle. Whereas you are but men and have infirmities as well as others, yet ye would make yourselves as holy as Angels.”

The Puritan Pejorative

As this early usage shows, “Puritan” started as an insult, often hurled at those in the sixteenth-century English church whose insistence on continual reformation and personal piety gave off a “holier-than-thou” attitude to their detractors. But the insult found new life as a badge of honor. The exchange of Zelotes and Atheos opens a fictional dialogue written by minister George Gifford called Country Divinity (1581). It claimed to describe the religion of the “common sort” of Christian who inhabited English parishes. The story’s characters read like religious caricatures: a zealous Puritan and a recalcitrant layperson. Puritans such as Gifford saw their life’s work as bringing the full fruits of the Protestant Reformation to every corner of England; dialogues like Country Divinity sought to edify the “godly” (as they called themselves) as they set out on this task.

For Puritans this task included the reformation of everything from theology to politics, education to recreation. Atheos didn’t quote the old proverb that a Puritan who minds his own business is a contradiction in terms. But where some like Atheos saw Puritans as “busy controlling,” others heard the call of God to continue reforming the English church.

A young person living in England in 1560 might have been forgiven for not knowing how to act or what to do in church. In a tumultuous decade and half, England had four different monarchs and with them, four competing visions of the English church. Henry VIII (1509–1547) broke with the Roman Catholic Church, and later a rapid Protestant overhaul occurred during the reign of his son Edward VI (1537–1553). However, reform came to a screeching halt when Edward’s older sister, Mary I (1516–1558) succeeded him. She restored English ties with Rome and reinstated Catholicism, persecuting subjects who did not abandon Protestant convictions.

Reforming politics

When Elizabeth I (1533–1603) came to the throne in November 1558, the country held its breath. Prudently she had kept her head down (and thus managed to keep it) during her sister Mary’s reign, so her personal religious opinions were the subject of some debate and remain so to this day. However, the young queen—25 years old at her accession—and her elder advisors wasted no time in another religious overhaul that once again reversed the Church of England’s course. She again broke ties with Rome and restored her half-brother’s Book of Common Prayer, mandating it for all services. But like every compromise worthy of its name, the “Elizabethan Settlement” left disgruntled parties on all sides.

Catholics felt the reforms went too far when they returned church control to the English Crown, thereby cutting off hopes of reunification with Rome. On the other hand, zealous Protestants, many newly returned from exile under Queen Mary, grumbled that the reforms had not gone far enough. Calvin’s reform model in Geneva, soon to be exported around both the Old World and the New, was fresh in the exiles’ memory. The Reformation was far from over.

The monarch had much control over sixteenth-century religious life, but Parliament limited that power. While the queen influenced debates, sometimes they took on a life of their own, and zealous Protestants pressed for more reform. In 1569 Cambridge preacher and scholar Thomas Cartwright (1535–1603) argued for a presbyterian church order (elder-assembly based) as opposed to the episcopal system (bishop based). The authorities’ reaction was so strong that he lost his university chair and had to flee to Geneva.

Not to be deterred, two young London ministers and Puritan firebrands, Thomas Wilcox (1549–1608) and John Field (1545–1588), picked up the torch and published an Admonition to the Parliament in 1572. Wisely they did so anonymously:

We in England are so far from having a church rightly reformed, according to the prescript of God’s Word that as yet we are not come to the outward face of the same.

They sought a church defined by “preaching of the word purely, ministering of the sacraments sincerely, and ecclesiastical discipline.”

The argument fell on mostly deaf ears, but the “Admonition Controversy” that followed was still influential. Public and often bitter debate on doctrine and politics played out in a series of polemical writings exchanged between status quo defenders and those who sought further reform. Cartwright returned and reentered the academic fray, while various Puritan-inclined members of Parliament maneuvered for advantage throughout the 1570s and the 1580s.

Eventually this “Puritan movement,” as historians call the coordinated political efforts aimed at reforming the church, began to die out in the 1590s. Authorities cracked down on ministers who refused to subscribe to the Book of Common Prayer. They imprisoned and occasionally executed recalcitrants who believed the Church of England to be beyond repair and chose to separate altogether. In case any hopes of restructuring along presbyterian lines lingered, Elizabeth’s successor, James I (James VI of Scotland, 1566–1625), made his sympathies clear immediately: “no bishop, no king.”

Yet the Puritan movement’s collapse did not spell Puritanism’s end. Political reform had never captured all the Puritan ethos. Indeed, some thought the gutter-level insults and political vitriol in these debates over church power and structure distracted from more important matters.

Puritans preferred ministers who could preach sermons tailored specifically for their flocks. They believed that the failures of the English church lay at the feet of its ill-trained clergy. Only an educated clergy could produce an educated and reformed laity. And if one’s minister left something to be desired, the more advanced Puritans might hop over to the next town to hear a more properly edifying sermon. This practice of “gadding about” undercut local clergy’s authority even as it revealed the strong demand for educated clergy.

One tool for ministers who lacked formal training or skills came in the “prophesyings,” or lectures by combination. These monthly clergy meetings involved multiple sermons on the same passage preached in succession, with each being followed by critical evaluation from the audience, mostly other clergy but possibly laity as well. Since prophesyings were often held in market towns and timed to coincide with market days, they could become quite a spectacle.

Educated resistance

Eventually the authorities had seen enough. In 1576 the queen ordered Archbishop of Canterbury Edmund Grindal (1519–1583) to suppress the prophesyings and restore order. Grindal, a former Marian exile, politely demurred. “Bear with me, I beseech you, Madam, if I choose rather to offend your earthly Majesty than to offend the heavenly Majesty of God.” For this stand of conscience, Grindal lost his authority, and the Crown’s grip on the church strengthened.

Although the prophesyings eventually ended, creative clergy found ways to connect and support each other. Wealthy and well-connected sympathizers established learning centers, such as Emmanuel College at Cambridge that functioned as a Puritan seminary. The increasing number of educated clergy and an explosion in cheap printed materials combined to leave a lasting impact on Puritan religious practices.

Puritans continued the Protestant emphasis on access to Scripture in the vernacular and encouraged private readings among laypeople with such works as the Geneva Bible, completed by Marian exiles in the latter 1550s. Indeed it is hard to imagine Puritanism without reading, and the rise in literacy that accompanied the increase of printed materials fed the growth of private devotion. But with increased study and meditation on sermons came questions.

While many Reformed theological emphases such as grace and providence might provide spiritual succor, others troubled anxious hearts or caused harm. Atheos lamented that preachers who prioritized predestination meddled “in such matters as they need not” and only served to make men worse by producing a sense of fatalism. Puritan theologians didn’t agree, but the complaint must have had staying power to find its way into a fictional dialogue.

Where Atheos of Country Divinity found cause for lament, some Puritans saw a challenge and calling. Skilled ministers like Richard Greenham (c. 1535–1594) came to be known for their expertise in “comforting the afflicted consciences” of their flock. With the elimination of the practice of confession came the loss of a key source of spiritual solace for the laity, and not everyone was skilled at navigating the landscape of the penitent heart.

Puritan preaching and devotional writing often included a cataloging of sins and vices and directed their hearers and readers inward to take their own spiritual inventories. However, this came with the risk that an overzealous audience might take such messages too much to heart, work their way into despair, and doubt the ability of God to redeem such a miserable sinner. The fine lines between despair of God’s grace and necessary repentance, or between humble or hubristic faith, required the guidance of steady hands like Greenham’s and those of other “spiritual physicians” who followed in his footsteps. And, unlike the failed political programs or the suppressed prophesyings, Puritan practical divinity thrived in ways that avoided condemnation and shaped expressions of Protestantism in the generations that followed. CH

By Scott McGinnis

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Scott McGinnis is professor of biblical and religious studies at Samford University.Next articles

“Viva! Viva! Gesù!”

In the wake of Protestant Reformation, Catholic reform rekindled love for Christ within the Catholic church

Shaun BlanchardRecovering “true Christianity”

Pietism stood at the forefront of renewal in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

J. Steven O’MalleySupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate