Living for Christ

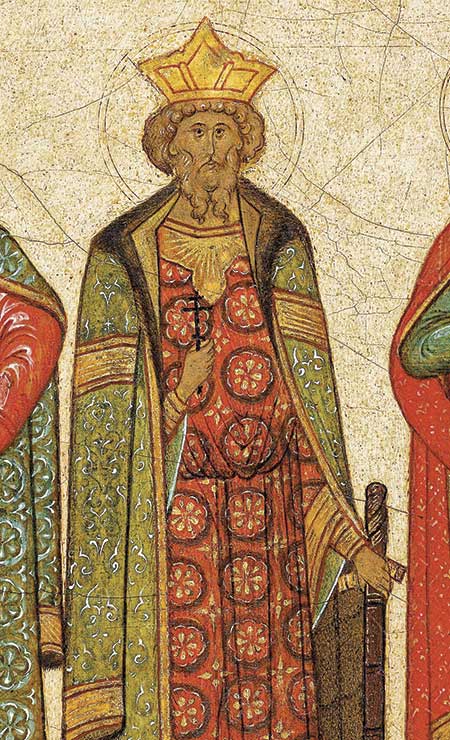

[The holy prince Volodymyr, detail, 16th C. Tempera on Canvas, Novgorod School—National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Why did these martyrs, theologians, missionaries, saints, and preachers make our top 100 most-searched topics online? You tell us! This new gallery retells the stories of some of our readers’ favorite figures from the past 149 issues.

Vibia Perpetua (c. 180–c. 202) made autobiography come alive

Perpetua, a well-educated Roman, the delight of her father, left a rare treasure: the first-known diary by a Christian woman. It vividly records her experiences on death row in third-century Carthage.

After she was arrested as a Christian, her father was frantic from the scandal and the fear of losing her. He begged her to renounce her faith for the sake of her newborn son.

“Father,” she answered, “Do you see this pitcher?”

“I see it.”

“Can it be called by any other name than what it is?”

“No.”

“Neither can I call myself anything but what I am—a Christian.”

Her father blustered but left defeated—“he and the arguments of the devil.”

Authorities thrust Perpetua and other Christians into a dungeon. “I was scared because I had never known such darkness,” she wrote. “O bitter day! There was a great heat because of the closeness of the air, there was cruel handling by the soldiers. Lastly I was tormented by concern for my baby.”

Eventually deacons bribed the guards to move the Christians into better quarters. They granted Perpetua permission to tend to her son, after which she compared the prison to a palace.

At trial Perpetua stood fast. Seeing that she affirmed Christ as Lord, the magistrate ordered her father beaten. Although sorry for her father, Perpetua refused to end his humiliation by sacrificing to the emperor. With the others she was condemned to face beasts in the arena.

Before the games Perpetua dreamed she defeated a hideous Egyptian. “And I awoke,” she wrote, “and I understood that I should fight, not with beasts but against the devil; but I knew that the victory would be mine.”

Bound in nets, Perpetua and her slave, Felicitas, were tossed by a mad heifer. Perpetua helped Felicitas up. The two modestly adjusted their garments. Soon afterward the Christians kissed each another and faced soldiers who finished them off. The inexperienced youth assigned to kill Perpetua struck a bone, causing her agony. She guided his sword to her throat.

Her faith inspired other martyrs. Her lively first-person narrative influenced later autobiographies including, in all likelihood, Augustine’s famous Confessions.

Origen (c. 185–c. 253) was the first to try to unify all Scripture

Origen produced Christianity’s first systematic theology. His attempt to organize all of the Bible’s teachings using tools of Greek philosophy was so influential that Gregory of Nazianzus described Origen as “the stone that sharpens us all.”

Despite intense study, which included learning Hebrew, Origen took positions in his First Principles and other writings that church consensus held to be wrong. Notably he anticipated the Arian heresy by teaching that Christ is not equal with the Father. Although it took the church two more centuries to settle the doctrines of Christ and the Trinity, that did not stop councils from declaring Origen a heretic.

Whether he was labeled a heretic or not, Origen loved Christ. Born in Alexandria, Egypt, around 185, he obtained a good education and, at his father Leonides’s insistence, memorized Scripture daily. When Leonides was arrested as a Christian, young Origen implored him to remain faithful. His mother kept him from joining his father in prison by hiding his clothes. Origen’s turn would come; 50 years later he was imprisoned and tortured for his faith.

Between the two persecutions, Origen won renown as a teacher and as a writer. Appointed head of a school with female pupils, he determined to avoid any hint of scandal by castrating himself—or so said his admirer, church historian Eusebius. Origen’s commentary on eunuchs makes it unlikely.

Origen’s most famous work was the now-destroyed Hexapla, which arranged the Hebrew Bible and various Greek translations in columns. Like the Hexapla thousands of Origen’s sermons, commentaries, lectures, and letters are lost or are preserved only in unreliable versions. One fragment that has survived is a prayer based on John 13:2–9:

Jesus, my feet are dirty. Come even as a slave to me, pour water into your bowl, come and wash my feet. In asking such a thing I know I am overbold, but I dread what was threatened when you said to me, “If I do not wash your feet I have no fellowship with you.” Wash my feet then, because I long for your companionship.

Key to Origen’s thinking was 1 Corinthians 15:26–28, that God will ultimately unify everything. Alexandrians accused Origen of teaching that even Satan will be reclaimed.

Forced to leave Alexandria, Origen established a school in Palestine. There he taught future Christian leaders. One of them, Gregory the Wonder Worker, admired Origen’s life and the way he presented Christ as “the Holy Word, the loveliest object of all, who attracts all irresistibly to himself by his unutterable beauty.”

Vladimir of Kyiv (c. 956–1015) established orthodoxy in Eastern Europe

Prince Vladimir of Kyiv was a warrior who united lands from Ukraine to the Baltic Sea. Although his grandmother Olga had promoted Christianity in the 950s, Vladimir began his rule as a pagan.

According to a twelfth-century chronicle, after Muslims reproached his lack of faith, he began to show interest in theirs. He liked their idea of sexual pleasures in heaven but balked at circumcision and abstinence from alcohol and pork, which were indispensable to Russian life.

Alarmed that Muslims might gain a hold over Vladimir, other religious traditions vied for preference. Jews, Catholics, and Orthodox advocated their own systems. When Vladimir learned that God had exiled the Jews for their sins, he dropped Judaism from consideration. Before deciding between the remaining alternatives, he sent envoys to Muslim Bulgaria, Catholic Germany, and Orthodox Constantinople.

The envoys were unimpressed with Bulgarian Islam and German Catholicism. By contrast they were overawed by Byzantine worship in Constantinople.

We know not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty . . . . We only know that God dwells there among men.

Probably the close proximity of Byzantium and its highly developed civilization had more to do with Vladimir’s choice than religious considerations. Emperor Basil II of Byzantium requested Vladimir’s military assistance. In return Vladimir demanded the emperor’s sister, Anna, as his wife. He even attacked a Byzantine city to force the issue. Told that Anna could not marry a non-Christian, he retorted that the emperor should send priests to baptize him. While instructing Vladimir in the basics of the Christian faith, the priests demonstrated God’s power by praying for Vladimir’s diseased eyes, which recovered.

Upon his return to Kyiv (c. 988), Vladimir destroyed idols and urged his people to adopt Christianity. About a year later, he led a mass baptism at which he prayed,

O God who created heaven and earth: look down upon these new people and grant them to know You, the true God.

Vladimir abandoned his playboy lifestyle and dismissed his multiple wives. He became kinder in his dealings. In his concern for the improvement of his nation, he promoted education, made judicial reforms, abolished the death penalty, assisted the poor, and built churches and monasteries. In 1015 he died in battle against a coalition formed by his rejected wives and their sons.

John Calvin (1509–1564) crafted lasting institutes

For many people Calvin’s name evokes one word: “predestination.” Few know of his conversion or of his years in danger and wandering.

Born in Noyon, France, John Calvin seemed destined for the Catholic Church. At age 12 he was given his first benefice (a paid church appointment) and was tonsured (shaved in priestly fashion). He studied literature and law. At 18 he was given another benefice for which he sometimes preached. But he did not yet know Christ. As he would later write, “Men are blind until Christ, who is the light of the world, enlightens them.”

Calvin’s enlightenment came around 1530. He recognized his depravity. Unable to find peace through the traditional Catholic means of sacraments and penance, he cast himself directly on God’s mercy in Christ. Following his conversion he joined evangelical Christians [that is, Lutherans] meeting secretly in Paris. When in 1533 a reformer preached a sermon that outraged Catholics, Calvin was implicated and had to flee in disguise.

He renounced his benefices. Sensing a call to restore pure Christianity, he issued the first version of his Institutes of the Christian Religion in March 1536. He would edit and expand it many times over the course of his life. It remains one of the best-known Protestant theological works.

In July 1536 Calvin passed through Geneva. Reformer Guillaume Farel ordered him to stay and develop its fledgling evangelical church. He spoke so fiercely that the reluctant Calvin felt he had no course but to agree. By 1538 Geneva had expelled them both. But in 1541 the troubled city pleaded with Calvin to return. Although Calvin would have preferred a life of scholarship, he accepted the challenge. He remade Geneva’s morals and its government. While preaching in February 1564, his mouth filled with blood. That sermon would be his last. He died in May.

Calvin’s record was marred by persecution of intellectual opponents and participation in judicial murders, most famously of Servetus. This was in accord with the practices of the age and does not diminish the value of his writings or of his model of church government. Through disciples such as John Knox, Calvin’s influence spread worldwide.

Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874) mothered the holiness movement

Phoebe Worrall was raised Methodist and committed herself early to following Christ. After she and Walter Palmer married, they engaged in Christian work in New York City. Death stalked their first three children. One, 11-month-old Eliza, lost her life through a fire caused by a careless servant. The baby girl died in Palmer’s arms.

In anguish over the tragedy, Palmer sought consolation in God’s word. Soul-searching showed her that she needed to be holy. One verse that arrested her attention was “Ye are not your own, ye are bought with a price: therefore glorify God in your body, and in your spirit, which are God’s” (1 Cor. 6:20). Her spiritual life had been fickle as weather: sunny one day, overcast another. Now she determined to surrender to God and to believe that his Spirit was in her. In her widely read The Way of Holiness with Notes by the Way, she described how she learned to trust God.

Fully aware that salvation is God’s gift, she also saw that Scripture teaches obedience as a condition to its enjoyment. She and her sister, Sarah Langford, began holding a women’s Bible study each Tuesday. Over the next four decades, Palmer taught, preached, wrote, issued magazines, organized revival meetings, promoted foreign missions, engaged in prison ministry, assisted the poor, and did whatever good she could.

Palmer’s desire for holiness (grounded in John Wesley’s teachings) led hundreds of thousands to pursue the same goal. Her theology of holiness inspired Wesleyans, Nazarenes, the Church of God (Anderson), the Salvation Army, and the later Pentecostal movement. By arguments and by actions, she also showed that women can be spiritual leaders on par with men.

Hudson Taylor (1832–1905) changed the way we do missions

Before his birth, Hudson Taylor’s parents dedicated him to missionary service. His mother did not tell him this until 1860, seven years after he had sailed from Liverpool, England, to spread the gospel in China.

As a youth Taylor sometimes behaved as a skeptic who mocked the hypocrisy of Christians. One day his mother, visiting a sister 50 miles from home, locked herself in a room and prayed until the Lord assured her Taylor would follow Christ. That same afternoon Taylor picked up a tract that described the finished work of Christ and gave his heart to the Savior. He later wrote, “A deep consciousness that I was no longer my own took possession of me.” He began to live a life of faith and set his eyes on the conversion of China.

Practical in outlook he used every reasonable means of preparation that God put within his reach. He disciplined his body, studied Chinese, trained in medicine, learned Scripture—and prayed. Years later, after he founded the China Inland Mission (CIM), his methods remained unchanged. He petitioned God directly for every need, whether it be for survival during danger, for more mission workers, or for funds to feed and clothe them. The two things he would not do were appeal for money or go into debt. The work was God’s, and God must provide for it.

The founding of China Inland Mission was a huge responsibility. During the months while he wrestled with the idea, Taylor feared he would have a nervous breakdown. One Sunday morning he wandered on a seashore alone, wrestling in prayer until God overcame his doubts.

Taylor transformed missions. He established his headquarters in China, rather than in England. He adopted Chinese dress and culture insofar as was practical. Rather than recruit for academic skills, he accepted people who had a heart for God and for evangelization. He gathered workers from many denominations. Despite dire warnings he appointed pairs of women to work without male counterparts.

CIM became the largest Protestant mission of the nineteenth century. God sustained it without financial appeals. The female teams flourished. CIM’s fervent workers experienced a higher percentage of martyrdom than those of any other mission. And, through their efforts, over 80,000 Chinese worshiped in CIM churches by 1897.

Watchman Nee (1903–1972) modeled churches that flourished in tough times

Nee was born into a Christian family in Shanghai. His parents provided him a top-notch education but he had little interest in Bible studies. At age 17, however, he experienced conviction and conversion under the preaching of Dora Yu and became eager to spread the gospel. Thereafter he joined with like-minded students to pray and to preach.

In 1920 Westerners still dominated the Chinese church. Nee’s greatest contributions were to free Chinese Christians from Western domination and to create a network of churches that met in homes. During the Japanese invasion and the Chinese civil war that followed, these decentralized “Little Flock” churches thrived. After the Communists took power in 1949, they were unable to crush the movement.

Nee published influential magazines and about 40 volumes of writings, some of them closely modeled on Western texts. Predicting the soon return of Christ, he called people to repentance. In books such as The Normal Christian Life, he proclaimed triumphant Christian living. However he was far from experiencing the victory he taught; for three decades he repeatedly engaged in sexual immorality and shady business dealings. During 10 of those years, he avoided taking Communion, probably because of his sense of guilt.

In 1952 the Communists imprisoned Nee. Although they charged him with espionage, tax evasion, and corrupt business practices, their real complaint was his refusal to submit to the Communist-run Three Self Patriotic Church. During 20 years of torture and abuse, Nee refused to renounce Christ, dying in prison.

His many writings were translated into numerous languages, and Little Flock churches survive to this day. As for Nee’s flawed character, a nephew reminded readers of several sinful Bible figures, writing,

Likewise, my uncle had failures. Yet . . . God has used him mightily. He is among the lowly, he is incomplete, yet he was truly used by God mightily and he was a vessel filled with precious treasure.

Corrie ten Boom (1892–1983) showed the power of love and forgiveness

During the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands in World War II, the ten Boom family aided and protected about 800 persecuted Jews. Eventually the ten Booms were betrayed and arrested. Several died in concentration camps or soon after their release.

Cornelia “Corrie” ten Boom was one who survived. Arrested in February 1944, she was in various prisons until late December that year. In each she assisted fellow prisoners and pointed them to Jesus. Her sister Betsie died, but not before telling Corrie of a vision she had been given of a home where Corrie would help other survivors.

After the war ten Boom did establish a ministry to help survivors of the concentration camps. She “tramped” the world, speaking of the love of Christ. “You can never learn that Christ is all you need, until Christ is all you have,” she said.

In telling her story, she insisted on the power of forgiveness. This was not an abstract concept for her. After one speech she was confronted by a former guard from Ravensbrück concentration camp—a guard who had been cruel to her sister Betsie. When he implored her forgiveness, ten Boom had to send up an inward prayer before she was able to clasp his hand. She observed that survivors who forgave their oppressors came through their trials best. “Forgiveness is an act of the will, and the will can function regardless of the temperature of the heart.”

Although ten Boom was just one of hundreds of thousands who suffered under the Nazis, her story became known worldwide through books such as In My Father’s House and the movie The Hiding Place. Christianity has always been about love and forgiveness. Ten Boom exemplified both, showing how Christ empowers ordinary Christians to triumph over brutality. CH

By Dan Graves

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #150 in 2024]

Dan Graves does layout for CH and writes for Christian History Institute (CHI).Next articles

Recommended resources: Stories worth retelling

We covered a lot of ground in this issue of CH! Here are just a few resources we recommend to learn more.

the authors and editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate