A long road

[African slave woman / WIkimedia]

MALINTZIN WAS BORN in Coatzacoalcos, a town of Nahuatl and Popoluca speakers along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, during the early 1500s. While still a child, she was sold or pawned to long-distance slave traders bound for Potonchán in the Maya region. For several years she labored as a domestic slave and concubine in Potonchán, learning the local language and adapting to everyday life under the Maya.

When the expedition led by Hernán Cortés arrived and battled the men of Potonchán in 1519, Malintzin and several other native women were given as slaves to the conquistadors as a sign of peace. In the words of historian Frances Kartunnen, “the women were summarily baptized and distributed to provide the [invading] men with sexual services.” This was their brutal introduction to Christianity.

Despite enduring this serial sexual exploitation, Malintzin, who possessed strong linguistic ability, quickly learned Spanish and became a key interpreter in the negotiations between Cortés and the agents of Montezuma II, the ruler of the Mexica Empire. She gave birth to two children: Martín Cortés, Hernán’s son; and María Jaramillo, daughter of another conquistador. But due to her association with the most influential conquistador in Mexico, they never suffered the fate of other enslaved people. Malintzin led an exceptional life given her role in the fall of the Mexica Empire, but her status as an indigenous slave-concubine was common—before and after conquest.

Variations on a theme

Slavery in the region we now know as Latin America preceded the arrival of Spanish and Portuguese expedition parties. It may be tempting to tie down the arrival of Christianity and slavery to the pioneering voyages of Columbus in 1492 and Pedro Álvares Cabral (1467–1520) in 1500, but to do so would be to erase historical complexity, political intrigues, and military ambitions from the relationship between religion and enslavement in colonial Latin America.

Before the arrival of the explorers, enslaved people fulfilled a variety of roles—as domestic servants, porters, and concubines, for instance. Depending on the social, political, and cultural organization of any given group, captive women and children might be gradually incorporated as kin, or they might remain outside full membership in society.

The children of enslaved people did not automatically inherit their parents’ condition. In Central Mexico, for instance, a person could be enslaved for committing a serious crime. In other cases especially impoverished families pawned themselves or their children into slavery. Throughout wide swaths of the Americas, indigenous people also ritually sacrificed enslaved warriors and other captives, either to maintain a cosmic balance or in homage to specific deities as part of a pre-established ritual calendar.

Slaves for generations

The arrival of the Iberian explorers at the end of the fifteenth century radically altered the practice of slavery in the Caribbean, Central Mexico, and Peru, and along the Brazilian coastline. The Spanish and Portuguese brought with them the concept of partus sequitur ventrem, originally a Roman principle that transmitted slavery through the womb of an enslaved woman. This enabled them to lay the foundation for generations of slavery as long as captive women reproduced.

The decimation of indigenous people on the islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico soon led to a large-scale slave trade from the mainland and the Lesser Antilles to replace those who had died from newly introduced diseases (smallpox, swine flu, influenza, typhoid, and meningitis) or from physical abuse and famine. Determining the free or slave status of any given indigenous woman became of paramount importance; her status determined the status of her children.

Branding “legitimate” captives—especially native women—became a common practice during the early sixteenth century. Very few Iberian women took part in these first European expeditions, and many Portuguese and Spanish men took native women as concubines. Some eventually married the mothers of their children in the Catholic Church, but most did not.

In territories colonized by Spain, the Catholic Church had a greater impact on slaving practice than in other regions. This was especially true of viceregal (colonial) capitals, such as Mexico City and Lima, or other cities where bishops’ sees were established, like Puebla or Quito. Missionaries, such as the influential Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566), believed that indigenous people should be considered potential Christians, able to understand the faith and be baptized.

This soon led to fierce debates in the 1540s and 1550s on the incompatibility of Christianity with mass enslavement; religious orders had also held slaves and benefited from their labor. Las Casas was instrumental in the passage of the New Laws of 1542, by which the Spanish crown formally abolished indigenous slavery in its American domains and also officially ended the encomienda system (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). Exemptions were made when native groups resisted being colonized. By contrast the abolition of African slavery would not come ntil 400 years later.

An ever-elusive freedom

Iberians associated Africans with the “Moors” (Muslims) of North and West Africa and considered them culturally and religiously inferior to Christian Europeans. Since the first slaving voyages from West Africa to Portugal in the 1440s, Portuguese and Spanish colonizers had normalized African slavery and proclaimed it compatible with Christianity. By the time of Columbus a half century later, the idea of the inferiority and rightful subjugation of African peoples was firmly enmeshed in the European imagination.

Portuguese slavers had a lucrative business selling African captives to slaveholders in Spanish cities. Whether these enslaved Africans eventually converted, married as Christians, or had their children baptized in no way altered their status as human property. The deployment of enslaved Africans to the colonies simply extended a slaving logic already in place. The demographic collapse of native populations from disease and the abolishment of indigenous slavery in 1542 cemented the association between blackness and enslavement in colonial Latin America.

Only a handful of religious men openly defied this mass enslavement. In a 1560 letter to the Spanish king, archbishop of Mexico Alonso de Montúfar (1489–1572) argued there was no legitimate reason for “blacks to be any more captive than Indians,” especially because Africans had shown time and again “their good will in receiving the Holy Gospel.”

Montúfar also rejected the alleged “spiritual benefits” enslaved Africans received while in Christian captivity. For example, he said, when enslaved Africans married in Mexico, they actually committed bigamy as they had been forced to leave behind “their natural and legitimate wives and husbands in their [home]lands,” which caused “great damage to their salvation.”

Despite the influence of his position, the archbishop’s pleas fell on deaf ears. The transatlantic slave trade to Spanish America only intensified. Recent research proves that at least 528,000 African captives disembarked in the Spanish colonies before 1641. A minimum of 250,000 captured Africans also fell victim to the early slave trade to Brazil.

The immensity of that captive population with its diverse cultural and religious composition resulted in myriad adaptations of African practice to Christianity in the Latin American context. The Cuban tradition of Santería resulted from a combination of the Yoruba religion from Africa with Catholicism; Candomblé developed in a similar way in Brazil.

Enslaved people experienced varying levels of interaction with the Catholic Church depending on where they lived, which also in turn influenced their practice of the faith. Those in rural areas typically were less exposed to Christian doctrine; urban slaves by contrast had access to local parish churches and to churches, schools, hospitals, and convents run by Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits (and other smaller competing orders).

With greater access to Christian teaching and concentrated religious networks, both free and enslaved urban blacks began to carve out a number of religious brotherhoods, commonly known as confraternities, or cofradías. As African populations grew in the cities of Cartagena, Quito, Puebla, and others, so did the number of black brotherhoods.

In some cases ethnically specific confraternities emerged; in Mexico City, people of the Zape nation (modern-day coastal Sierra Leone) formed their own brotherhood in the Hospital of the Immaculate Conception. Over time these would gradually change in membership as members of one specific ethnic group gave way to their American-born descendants. In this way a “Congo” brotherhood could gradually morph into a “black” or “Creole” confraternity.

Black confraternities incorporated people of African descent into Catholicism spatially, financially, and socially. Church leaders were willing to assign specific chapels or side altars to devotees of a given brotherhood—not an insignificant gesture to enslaved or recently freed people. The confraternities also pooled membership fees to pay for the funerals of deceased members or even to purchase freedom papers. This created community and allowed African-descended people to adopt alternative identities as members (cofrades) and leaders (mayordomos) of a specific brotherhood.

Benefits of brotherhood

Like their indigenous counterparts, these African transplants often syncretized Christianity with traditional religions and expressed their faith in a particularly African manner. For instance in the late sixteenth century, the Franciscan convent of Puebla housed a brotherhood that venerated Benedict of Palermo, a black Sicilian holy man who would not be canonized until 1807. In Brazil the cult of the holy Ethiopian woman Santa Ifigenia was widespread among communities of African descent (and continues to be so).

As African populations venerated these black saints, they often neither fully accepted Christian doctrine nor abandoned prior religious beliefs, but used the multiplicity of Catholic saints as “stand-ins” for African deities. In Santería the figure of Saint George represents Ogún, while the Virgin Mary can stand in for Yemanyá, goddess of maternal love and the sea. Similar associations can be found in other syncretic religious systems throughout modern-day Brazil, Haiti, Cuba, and other places where the descendants of enslaved Africans live. Yet for some further removed from African religious practices, the brotherhoods offered avenues toward a more orthodox engagement with colonial Catholicism, allowing them to shed the harshest constraints of generational subjugation.

Born into slavery in Puebla in the mid-seventeenth century, Felipe Monsón y Mojica, a mulato or pardo, a man of partial African ancestry, eventually gained his freedom. He married Juana María de la Cruz, an indigenous woman, in the 1660s, and she enabled him to purchase his freedom papers. Together the two managed an extremely profitable business, selling chile peppers and other agricultural products in the city’s central plaza. In 1664 records show that he went into debt to expand the business:

I, Felipe de Mojica, free mulato of this city of de los Angeles, owe and am committed to paying Ignacio de Orrega, merchant and vecino of this city, and to anyone who might hold his power 3844 pesos of common gold. He has lent and supplied me this money in reales to purchase chile peppers, beans, and other things to sell in the stand that I have in this city’s public plaza.

After satisfying his debt, Monsón y Mojica turned his attention to the confraternity of the Expiración de Cristo, whose chapel was located within a local hospital. Throughout the 1670s and 1680s, he and Juana invested thousands of pesos in the chapel, commissioning indigenous master artisans to embellish its altar and making sure its members were properly outfitted for their Easter celebrations. As the leader of a well-respected black brotherhood, Monsón y Mojica had transcended his former slave status to establish himself as a model of Catholicism for other people of African descent.

In some ways Monsón y Mojica’s story echoes Malintzin’s. But we must also remember that we know his name, and hers, because they were unusual; most enslaved people entered the historical record as human property, devoid of personhood. For millions who never achieved their prominence, slavery was an even harder and more horrifying road. CH

By Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva is assistant professor of history at the University of Rochester and the author of Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico.Next articles

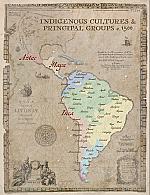

Map: Indigenous cultures & principal groups, c. 1500

Map of indiginous groups when Europeans arrived in the new world

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate