Wrestling with doubt

NO ASPECT of Darwinism distressed Christians more than Charles Darwin’s indelicate announcement in The Descent of Man (1871) that humans had “descended from a hairy quadruped, furnished with a tail and pointed ears.” Darwinism, complained one critic, “tears the crown from our heads; it treats us as bastards and not sons, and reveals the degrading fact that man in his best estate—even Mr. Darwin—is but a civilized, dressed up, educated monkey, who has lost his tail.”

There is no evidence to suggest, however, that many early creationists took the prospect of human evolution seriously enough to be more than rhetorically distressed. Surprisingly evolution became implicated relatively infrequently in the loss of religious faith. A number of years ago, sociologist Susan Budd studied 150 British secularists and freethinkers who lived between 1850 and 1950 seeking to discover whether encountering Darwinism and higher biblical criticism had been “especially responsible for weakening belief in the literal truth of scriptural religion for some, and for forcing others to abandon belief in God altogether.”

She found that only two of her subjects “mentioned having read Darwin or Huxley before their loss of faith.” Darwin himself rejected Christianity less because of his scientific discoveries than because he found the idea of punishing unbelievers forever “a damnable doctrine.”

From praying to farming

Some writers left personal testimonies about the corrosive effects of evolution on their religious beliefs. But in many cases, their encounters with Darwin’s theory came as part of a larger journey away from faith.

Victorian writer Samuel Butler supposedly told a friend that Origin of Species had completely destroyed his belief in a personal God. But one of his biographers noted, “He had . . . already quarreled with his father [a minister], refused to be ordained, thrown up his Cambridge prospects, and emigrated to New Zealand as a sheep-farmer before Darwin’s book came out.” He quit praying the night before he left for the Antipodes to start farming.

Few of Darwin’s contemporaries left evidence of experiencing such spiritual crises. One who did was naturalist Joseph LeConte. Arguably the most influential American harmonizer of evolution and religion in the late 1800s, he took great pride in showing that “evolution is entirely consistent with a rational theism.” But this did not come without a struggle.

The traumatic death of LeConte’s two-year-old daughter in 1861 left him clinging tenaciously to the doctrine of immortality. LeConte repeatedly alluded to his “distress and doubt” as “one who has all his life sought with passionate ardor the truth revealed in the one book [nature], but who clings no less passionately to the hopes revealed in the other [the Bible].” He wrote of his struggle with faith in his book Religion and Science, a Series of Sunday Lectures:

During my whole active life, I have stood just where the current runs swiftest. . . . I have struggled almost in despair with this swift current. I confess I have sometimes wrestled in an agony with this fearful doubt, with this demon of materialism, with this cold philosophy whose icy breath withers all the beautiful flowers and blasts all the growing fruit of humanity. This dreadful doubt has haunted me like a spectre, which would not always down at my bidding.

By the late 1870s he had evolved into a “thorough and enthusiastic,” if somewhat unorthodox, evolutionist. He insisted that there was “not a single philosophical question connected with our highest and dearest religious and spiritual interests that is fundamentally affected, or even put in any new light, by the theory of evolution.”

Actually, it is difficult now to sort out which orthodox doctrines he ditched because of evolution and which ones he abandoned for other reasons. But, by the last decade of his life, he had come to reject the idea of a transcendent God, the notion of the Bible as “a direct revelation,” the divinity of Christ, the existence of heaven and of the devil, the power of intercessory prayer, the special creation and fall of humans, and the plan of salvation. Only an imminent, pantheistic God and personal immortality survived. Yet, despite toying with leaving organized religion, LeConte continued to attend a Presbyterian church.

Now and then God comes in

George Frederick Wright was another who traveled this path. Wright, a seminary-trained Congregationalist minister and amateur geologist, emerged in the 1870s as a leader of the so-called Christian Darwinists and a recognized expert on the Ice Age in North America. As a young minister, he read Darwin’s Origin and Charles Lyell’s Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (1863).

These clashed with views he had been taught, but his autobiographical writings do not reveal whether or not the clash precipitated a crisis of faith. His writings indicate that he found in Harvard botanist Asa Gray’s writings a compromise—one that allowed him simultaneously to embrace organic evolution and to retain his belief in a divinely designed and controlled universe. Gray wrote that events in the world in general came simply from “forces communicated at the first,” but “now and then, and only now and then, the Deity puts his hand directly to the work.”

This view of God’s relationship to the natural world appealed to Wright as an ideal solution to reconciling science and Scripture. He blunted the possible psychological shock of Darwin’s theory by arguing that a theistic interpretation “makes room for miracles, and leaves us free whenever necessary, as in . . . the special endowments of man’s moral nature, to supplement natural selection with the direct interference of the Creator.” He also repeatedly used language that seemed to restrict natural selection to the lower end of the taxonomic scale while attributing kingdoms and broader taxonomic groupings to special creation.

Robbed of its sting?

Like Gray, Wright derived great comfort from Darwin’s inability to explain the origin of the variations preserved by natural selection. This limitation seemed to open the door for divine intervention. It “rob[bed] Darwinism of its sting,” “left God’s hands as free as could be desired for contrivances of whatever sort he pleased,” and preserved a “reverent interpretation of the Bible.”

Wright did experience a serious crisis of faith in the 1890s, but it came from encountering higher criticism of the Bible, not evolution. “So violent has been the shock,” he candidly reported, “that . . . I have found it necessary to turn a little aside from my main studies to examine anew the foundations of my faith.” Wright emerged from his soul-searching convinced more firmly than ever in the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch and in a supernatural view of history, and he turned sharply to the theological right. By the second decade of the twentieth century, he had joined the fundamentalist awakening, contributing an essay on “The Passing of Evolution” to The Fundamentals.

Few fellow fundamentalists at that time took evolution seriously enough to spend time refuting it scientifically. A significant exception was Canadian George McCready Price, who at the age of 14 joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Adventists commemorated a literal six-day creation by celebrating Sabbath on the seventh day and accepted as authoritative the visions and testimonies of their founder, Ellen G. White.

On one occasion she claimed to be “carried back to the creation and was shown that the first week, in which God performed the work of creation in six days and rested on the seventh day, was just like every other week.” White also endorsed the then largely discarded view of Noah’s flood as a worldwide catastrophe that had buried the fossils and reshaped the earth’s surface.

During the early 1890s, Price read for the first time about the fossil evidence for evolution. On at least three occasions, he later recalled, he nearly succumbed to the lure of evolution, or at least what he always considered evolution’s basic tenet: the progressive nature of the fossil record. Each time he was saved by sessions of intense prayer—and by reading White’s “revealing word pictures” of earth history.

As a result of this experience, he decided on a career championing what he called “flood geology” and what decades later came to be known as young-earth (or scientific) creationism. Price’s influence among non-Adventists grew rapidly. By the mid-1920s, the editor of Science described him as “the principal scientific authority of the Fundamentalists,” and Price’s byline was appearing with increasing frequency in many magazines. In the end, his thoroughgoing rejection of evolution gave direction to his life and served as the foundation of a rewarding career. CH

By Ronald L. Numbers

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #107 in 2013]

Ronald L. Numbers is Hilldale Professor of the History of Science and Medicine, Emeritus, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the author or editor of numerous books on science and religion. This article is adapted in part from Science and Christianity in Pulpit and Pew.Next articles

“What is Darwinism?”

A sampling of opinions from various theologians and scientists

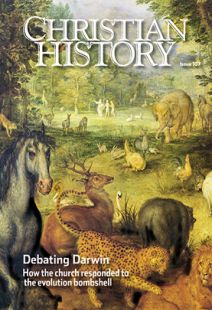

Elesha Coffman and the editorsEditor’s note: Debating Darwin

History turns out to be more complicated than we expect

Jennifer Woodruff TaitDivine designs

Conservative Christians moved from cautious consideration of Darwin to outright rejection

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate