Jeremiah through Zwingli's eyes- Zwingli's sources

Guest post by Dr. Jim West

Even though our four issues celebrating the 500th anniversary of the Reformation have passed, there are still many Reformation-related anniversaries to think about. It was January 1, 1519 when Zwingli began preaching through the Bible continuously in Zurich, an act which helped spark reform there. We are publishing this academic essay by Dr. West in three parts over the next few weeks to honor the 500thanniversary of that occasion.

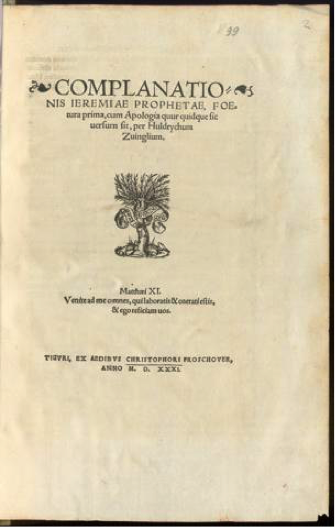

Heinrich Buchmann, about whom very little is known, arrived in Zurich in 1529 and became an ardent participant in the services of worship at the Great Minster. He was amazed by Zwingli’s preaching and it is to him that we owe the copious notes on Zwingli’s sermons on both Isaiah and Jeremiah. The second and third sources are the Complanatio and the German translation of the Prophets. These two, then, along with Buchmann’s notes (as later edited and published by Leo Jud) serve as the only sources we have for Zwingli’s exposition of Jeremiah. The Complanationis Ieremiae prophetae was published in 1531 and begins with a dedicatory letter to the Great Council of the City of Zurich. Following that dedication, Zwingli offers a translation of Jeremiah into Latin as well as a translation of the Book of Lamentations, which has historically been attributed to Jeremiah and thus is treated by Zwingli in conjunction with Jeremiah.

Immediately following the translation into Latin of Lamentations, Zwingli begins his exposition, word by word and line by line of the Latin text of the Book of Jeremiah. So, for instance, of “Sermones Ieremiae” elicits the following opening expository phrase: “The Hebrew word utilized in this place is דבר(davar) and itself means sermon, oration, reasoning, etc…” And so throughout, Zwingli follows the underlying text with exposition and exegesis. Some explanations are quite short, sometimes just consisting of a few words, and other times carrying on for page after page, all dependent on the importance of the word or phrase as determined by Zwingli’s exegetical purpose.

Zwingli also draws from not only the Hebrew text but the Septuagint as well. If the LXX makes a point which Zwingli wishes to emphasize, he feels free to focus on it more than on the underlying Hebrew text or the Latin translation. For instance, regarding “Reginae coela” in chapter 7 he notes that the LXX’s rendition is superior to the Vulgate and further opines that Jerome’s Latin is not quite on the mark, so that the clearer rendition of the LXX is to be preferred.

Zwingli’s exegesis in the Complanationisis, in some ways, quite “historical-critical” (though of course that phrase is anachronistic). That is, he focuses primarily on the literal meaning of the text rather than on an allegorical reading. Take, for example, his remark about Jeremiah 31:33 where Jeremiah has “…and I will write them on their hearts, etc”:

This phrase should be taken as meaning the viscera of the intellect, for to the Hebrews this is not found in the fat on the inside of the bowels but rather the heart, since it is the stony heart that is the location of the writing. The heart is the seat of the intellect.

Zwingli understands Hebrew anthropology in the same way that modern scholars do.

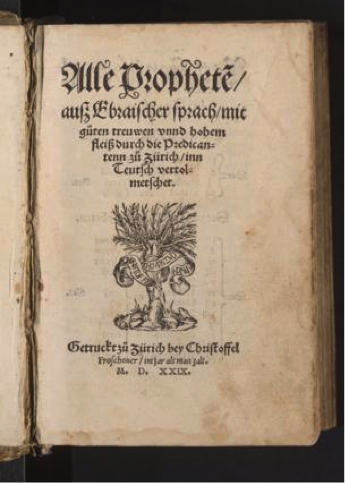

The German translation of the Prophets, later incorporated into the Zurich Bible of 1531, contains the “Four Great Prophets” (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel) and the “Twelve Minor Prophets” (Hosea – Malachi). The volume also contains a “Preface to the Prophets” and the whole is the result of the work of Zwingli and others during the “Prophezei”, the daily meeting of the Clergy of the Canton of Zurich during which the Bible was translated and exegeted by a host of learned academics holding to Zwingli’s views. This translation of the Bible is incredibly well done. A sample is below.

Alongside these three primary sources, two special studies have been published which discuss Zwingli’s exposition of Jeremiah (within the wider context of his exposition of the Hebrew Bible). The first is Huldreich Zwinglis hebräische Bibel, by Herbert Migsch, and by the same author, Noch einmal: Huldreich Zwinglis hebräische Bibel. Aside from these scant materials, very little has been published on the topic of Zwingli’s exegesis of the Old Testament in general or the Prophet Jeremiah in particular.

You can find out more about Zwingli and the Reformation in Christian History #118: The People's Reformation.

Dr. Jim West (ThD) is lecturer in biblical studies and Reformation history at Ming Hua School of Theology and pastor of Petros Baptist Church in Petros, TN. He also blogs on Reformation history at http://zwingliusredivivus.wordpress.com.