#408: The Quietists

“Our vain desires and our self—love confuse the voice within us.” Molinas, Guyon, and Fenelon: The 17th-Century Quietists.

Introduction

After the Reformation, there was a reaction in Catholic lands, commonly known as the Counter-Reformation. One strand of that was a mystical movement known as Quietism. Its influence was felt not only in Catholic countries but in Protestant circles.

Quietists had something of the Stoic about them, a passivity and silence in the face of outward events. They declared that nothing of spiritual value can originate in man. Religious life must therefore be a divine movement within the soul. The Quietists strove to crush their own will, and any desire—even the desire for salvation—so that God could bring about whatever he desired without impedance from the human.

Everything that happens, they believed, is prescribed for the good of the soul by God. Therefore it is all to be accepted quietly. The orders of the Catholic church and one’s superiors, even if wrong, must therefore be obeyed.

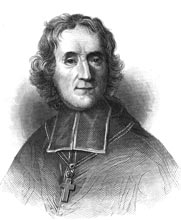

Three leading Quietists, in order of appearance, were: Miguel de Molinos (1627-1696); Jeanne Marie Bouvier de la Mothe Guyon (1648-1717); and François de la Mothe Fenelon (1651-1715). There were other significant Quietists, but these are the best-known in English-speaking lands.

Molinos, a Spaniard, originated the movement with his Spiritual Guide. For years he was acclaimed for this book, received the approbation even of the Inquisition, and gathered numerous followers. However, the tendency of Quietists to dispense with formal religion made Molinos’ teaching suspect. Also, there were many, especially among the Jesuits, who envied his success. He was imprisoned, tortured, and tried, but (because of his own teachings) refused to say a word in his own defense during the proceedings, although he escaped the stake by recanting his views. Eventually, he was banished to a Dominican monastery, where he soon died.

Madame Guyon was a French woman forced into marriage with a rake. Her in-laws oppressed and even imprisoned her when she adopted Quietist teachings and practices. At one point Guyon claimed mystical union with God. Imprisoned, she recanted her teachings. Ironically, many of her Huguenot compatriots, who made no such exalted claims as union with God, nonetheless endured persecution, torture, and death without flinching or betraying their beliefs. Following her recantation, Guyon was freed and finished her life in quiet seclusion. Her writings greatly influenced Fenelon.

Fenelon was archbishop of Cambrai, a man of beautiful and noble character, who wrote spiritual classics and played an important part in France. At one point, he published quotations from the church fathers to defend Guyon’s Quietism. When the pope condemned portions of this, Fenelon submitted to the verdict without protest just as his Quietist principles required.

Quietism is a doctrine beset by many difficulties. It hardly seems reconcilable with the man/God relationship depicted in scripture, nor with certain divine commands and promises, which teach us to seek, request, labor, wrestle, stand, and strive; nor does it seem in full accord with the exemplary prayers of scripture, including Christ’s in the Garden of Gethsemane in which the saints poured out their anguish to the Father submitting but not suppressing.

Because these three Quietists suffered at the hands of the Catholic church, Protestants have viewed them sympathetically. They strongly influenced Protestant evangelicals, mystics, and holiness advocates. Therefore, we present a selection from each of them.

Molinos. Spiritual Guide Part II Chapter XIX: “Of true and perfect annihilation."

Thou must know that all this fabric of annihilation hath its foundation but in two principles. The first is, To keep one’s self and all worldly things in a low esteem and value; from whence the putting in practice of this self-divesting, and of self-renunciation, and forsaking all created things, must have its rise, and that with affection and in deed.

The second principle must be a great esteem of God, to love, adore, and follow Him without the least interest of one’s own, let it be never so holy. From these two principles still arise a full conformity to the Divine will. This powerful and practical conformity to the Divine will in all things leads the soul to annihilation and transformation with God, without the mixture of raptures, or external ecstasies, or vehement affections. This way being liable to many illusions, with the danger of weakness, and anguish of the understanding, by which path there is seldom any that gets up to the top of perfection, which is acquired by the other safe, firm, and real way, though not without a weighty cross; because therein the highway of annihilation and perfection is founded, which is seconded by many gifts of light, and Divine effects, and infinite other graces. Yet the soul that is annihilated must be unclothed of it all, if it would not have them be a hindrance to it in its way to deification.

As the soul makes continual progress from its own meanness, it ought to walk on to the practice of annihilation, which consists in the abhorring honor, dignity, and praise, there being no reason that dignity and honor should be given to vileness and a mere nothingness.

To the soul that is sensible of its own vileness, it appears an impossible thing to deserve anything; it is rather confounded, and knows itself unworthy of virtue and praise; it embraces with equal courage all occasions of contempt, persecution, infamy, shame, and affront, and as truly deserving of such reproaches; it renders the Lord thanks, when it lights upon such occasions, to be treated as it deserves; and knows itself also unworthy that He should use His justice upon it; but above all it is glad of contempt and affront, because its God gets great glory by it.

Such a soul as this always chooses the lowest, the vilest, and the most despised degree, as well of place as of clothing, and of all other things, without the least affectation of singularity; being of the opinion that the greatest vileness is beyond its deserts, and acknowledging itself also unworthy even of this. This is the practice that brings the soul to a true annihilation of itself.

The soul that would be perfect begins to mortify its passions; and when it is advanced in that exercise, it denies itself; then, with the Divine aid, it passes to the state of nothingness, where it despises, abhors, and plunges itself upon the knowledge that it is nothing, that it can do nothing, and that it is worth nothing. From hence springs the dying in itself, and in its senses, in many ways, and at all hours; and finally, from this spiritual death the true and perfect annihilation derives its original; insomuch, that when the soul is once dead to its will and understanding, it is properly said to be arrived at the perfect and happy state of annihilation, which is the last disposition for transformation and union which the soul itself doth not understand, because it would not be annihilated if it should come to know it. And although it do get to this happy state of annihilation, yet it must know that it must walk still on, and must be further and further purified and annihilated.

You must know that this annihilation, to make it perfect in the soul, must be in a man’s own judgment, in his will, in his works, inclinations, desires, thoughts, and in itself; so that the soul must find itself dead to its will, desire, endeavour, understanding, and thought; willing, as if it did not will; desiring, as if it did not desire; understanding, as if it did not understand; thinking, as it it did not think, without inclining to anything; embracing equally contempts and honors, benefits and corrections. Oh, what a happy soul is that which is thus dead and annihilated! It lives no longer in itself; because God lives in it. And now it may most truly be said of it, that it is a renewed phoenix, because it is changed, spiritualised, transformed, and deified.

Madame Guyon. Excerpts from Autobiography, Volume II.

My interior state was continually more firm and immovable, and my mind so clear, that neither distraction nor thought entered it, save those it pleased our Lord to put there. My prayer, still the same—not a prayer which is in me, but in God—very simple, very pure, and very unalloyed. It is a state, not a prayer, of which I can tell nothing, owing to its great purity. I do not think there is anything in the world more simple and more single. It is a state of which nothing can be said, because it passes all expression—a state where the creature is so lost and submerged, that though it be free as to the exterior, for the interior it has absolutely nothing. Therefore its happiness is unalterable. All is God, and the soul no longer perceives anything but God. She has no longer any pretence to perfection, any tendency, any partition, any union; all is perfected in unity, but in a manner so free, so easy, so natural, that the soul lives in God and from God, as easily as the body lives from the air it breathes. This state is known of God alone, for the exterior of these souls is very common, and these same souls, which are the delight of God, and the object of his kindness, are often the mark for the scorn of creatures. (p. 55)

One day, as I was thinking to myself how it happens that the soul who commences to be united to God, although she finds herself united to the saints in God, has yet hardly any instinct to invoke them, it was put into my mind that servants have need of credit and intercessors, but the wife obtains all from her husband even without asking him for anything. He anticipates her with an infinite love. O God, how little they know you! They examine my actions; they say I do not repeat the Chaplet, because I have no devotion to the Holy Virgin.

O divine Mary, you know how my heart is yours in God, and the union which God has made between us in himself, yet I cannot do anything but what Love makes me do.

I am altogether devoted to him and to his will. (p. 205)

Francois Fenelon. “The Spirit of God Teaches Within."

It is certain, that the scriptures declare that “the Spirit of God dwells within us,” that it animates us, speaks to us in silence, suggests all truth to us, and that we are so united to it, that we are joined unto the Lord in one spirit. This is what the Christian religion teaches us. Those learned men, who have been most opposed to the idea of an interior life, are obliged to acknowledge it. Notwithstanding this, they suppose that the external law, or rather the light from certain doctrines and reasonings, enlightens our minds, and that afterwards it is our reason that acts by itself from these instructions. They do not attach sufficient importance to the teacher within us, which is the Spirit of God. This is the soul of our soul, and without it we could form no thought or desire. Alas! then, of what blindness we are guilty, if we suppose that we are alone in this interior sanctuary, while, on the contrary, God is there even more intimately than we are ourselves.

You will say, perhaps, Are we then inspired? Yes, doubtless, but not as the prophets and the apostles were. Without the actual inspiration of the Almighty, we could neither do, nor will, nor think anything. We are then always inspired; but we are ever stifling this inspiration. God never ceases to speak to us; but the noise of the world without, and the tumult of passions within, bewilder us, and prevent us from listening to him. All must be silent around us, and all must be still within us, when we should listen with our whole souls to this voice. It is a still small voice, and is only heard by those who listen to no other. Alas! how seldom is it that the soul is so still, that it can hear when God speaks to it. Our vain desires and our self-love confuse the voice within us. We know that it speaks to us, that it demands something of us; but we cannot hear what it says, and we are often glad that it is unintelligible. Ought we to wonder that so many, even religious persons, who are engrossed with amusements, full of vain desires, false wisdom, and self-confidence, cannot understand itj and regard this interior word of God as a chimera?

This inspiration must not make us think that we are like prophets. The inspiration of the prophets was full of certainty upon those things that God commanded them to declare or to do; they were called upon to reveal what related to the future, or to perform a miracle, or to act with the divine authority. This inspiration, on the contrary, is without light and without certainty; it limits itself to teaching us obedience, patience, meekness, humility, and all other Christian virtues. It is not a divine monition to predict, to change the laws of nature, or to command men with an authority from God. It is a simple invitation from the depths of the soul, to obey, and to resign ourselves even to death, if it be the will of God. This inspiration, regarded thus, and within these bounds, and in its true simplicity, contains only the common doctrine of the christian church. It has not in itself, if the imaginations of men add nothing to it, any temptation to presumption or illusion; on the contrary, it places us in the hands of God, trusting all to his Spirit, without either violating our liberty, or leaving anything to our pride and fancies.

If this truth be admitted; that God always speaks within us, he speaks to impenitent sinners; but they are deafened and stunned by the tumult of their passions, and cannot hear his voice; his word to them is a fable. He speaks in the souls of sinners who are converted; these feel the remorse of conscience, and this remorse is the voice of God within them, reproaching them for their vices. When sinners are truly touched, they find no difficulty in comprehending this secret voice; for it is that which penetrates their souls; it is in them the two-edged sword of which St. Paul speaks. God makes himself felt, understood, and followed. They hear this voice of mercy, entering the very recesses of the heart, in accents of tender reproach, and the soul is torn with agony. This is true contrition.

God speaks in the hearts of the wise and learned, of them whose regular lives appear adorned with many virtues; but such persons are often too full of their own wisdom; they listen too much to themselves to listen much to God. They turn everything to reasoning; they form principles from natural wisdom and by worldly prudence, that they would have arrived at much sooner by singleness of heart and a docility to the will of God. They often appear much better than they are; theirs is a mixed excellence; they are too wise and great in their own eyes; and I have often remarked, that an ignorant sinner, who is beginning in his conversion to be touched with the true love of God, is more disposed to understand this interior word of the Spirit, than certain enlightened and wise people who have grown old in their own wisdom. God, who seeks to communicate himself, cannot be received by these souls, so full of themselves and their own virtue and wisdom; but his presence is with the simple. Where are these simple souls? I see but few of them. God sees them, and it is with them that he is pleased to dwell. “My Father and I,” says Jesus Christ, “will come unto him, and make our abode with him.”

Bible Verses

Matthew 6:9—13

Luke 13:24

1 Peter 1:17—19

Study Questions

“The second principle must be a great esteem of God, to love, adore, and follow Him without the least interest of one’s own, let it be never so holy.” Does this agree with the teaching of Jesus who said “Make every effort to enter the narrow gate"? Or with the Lord’s Prayer which gives us items to request? Can it be reconciled with the rewards set before us in scripture?

How does Molinos define soul annihilation? From which scriptures might he have arrived at his understanding? Is it a true principle of scripture?

If a soul is worth nothing, as Molinos says, why did Christ buy it with his blood, more precious than gold (as Peter tells us).

How does Madame Guyon describe her prayer state? Does this “prayer” compare favorably with the prayers found in the Psalms, in Christ’s teaching, and in Paul’s letters?

How does Madame Guyon describe our connection with the saints who have passed through death?

According to Madame Guyon, what analogy describes a Christian’s relationship to God, so that there is no need to invoke the saints?

According to Fenelon, who is the teacher within us? What Bible passages support this teaching?

What things does Fenelon see as preventing us from hearing God’s voice within us?

How does the Holy Spirit inspiration of ordinary Christians differ from that of the prophets in Fenelon’s view?

Fenelon says the “wise” have difficulty receiving the word of the Spirit. To what does he attribute this defect?

Next modules

Module 409: Butler’s Analogy

Quietism flares and fades.

Module 410: Jonathan Edwards on Free Will

Quietism flares and fades.

Module 411: John and Charles Wesley

Quietism flares and fades.

Module 412: William Wilberforce and Slavery

Quietism flares and fades.