The church of the bystanders

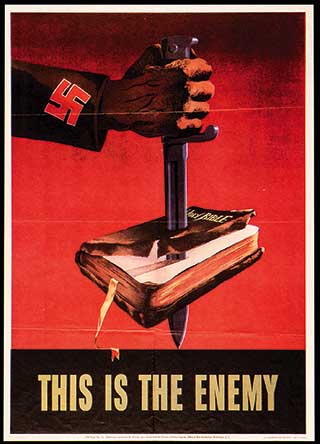

[anti-Nazi poster—Wikimedia]

IN 1998 Israeli scholar Yehuda Bauer was invited to speak before Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag. “I come from a people who gave the Ten Commandments to the world,” he told the legislators. “Time has come to strengthen them by three additional ones, which we ought to adopt and commit ourselves to: thou shall not be a perpetrator; thou shall not be a victim; and thou shall never, but never, be a bystander.”

During the 12 years of the Third Reich, Christians broke each of Bauer’s commandments. A few—both too many and not enough—sacrificed life or liberty to resist Nazi iniquity. But the vast majority of German Christians fell along that complicated spectrum between perpetrator and bystander.

The lesser of two evils?

How did this happen? The roots stretched back to the First World War. In 1914 most German Protestants (two-thirds of Germany’s population) participated gladly in what they saw as a crusade against their Catholic (French and Belgian) and Orthodox (Russian) national neighbors. Instead of taking out France and Russia, though, the costly war toppled the conservative German monarchy instead.

In its place came the Weimar Republic; this new democratic state got its nickname from the city of Weimar where its constitution was signed. Its socialist and liberal founders were forced to sign a harsh peace treaty that served as political fodder for right-wing groups like the National Socialists (Nazis). Even if they were put off by the violence of the Nazi “Brownshirts,” patriotic Protestants living in Stalin’s shadow could tell themselves that the stridently anti-Communist Nazis were the lesser of two evils.

On January 30, 1933, the conservative Protestant president, Paul von Hin-denburg, appointed a new chancellor: Adolf Hitler. Hitler led the largest party in the Reichstag (predecessor of the Bundestag).

Many clergy greeted this appointment gladly. The dean of Magdeburg Cathedral said about the cathedral’s Nazi flags, “Whoever reviles this symbol of ours is reviling our Germany. The swastika flags around the altar radiate hope—hope that the day is at last about to dawn.” Another pastor, Julius Leffler, announced, “In the pitch-black night of church history, Hitler became, as it were, the wonderful transparency for our time, the window of our age, through which light fell on the history of Christianity. Through him we were able to see the Savior in the history of the Germans.”

Just two days later, young pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer spoke on national radio. Having earlier campaigned against pro-Nazi candidates in church elections, Bonhoeffer proceeded to question Hitler’s leadership as well—prompting the radio station to mysteriously switch off his microphone before he could broadcast his closing statement, which included the line “Leaders [Führers] or offices which set themselves up as gods mock God.”

But protests like Bonhoeffer’s were unusual. As Hitler eliminated political opposition, removed Jews from public life, and started to “nazify” (place under Nazi control) many German institutions, Protestant clergy celebrated by holding mass baptisms for children left unchristened during the Weimar Republic’s more secular years.

Dreamers and the naïve

One who welcomed the Nazi revolution was minister Martin Niemöller. A former U-boat captain, Niemöller organized an anti-Communist militia after the war. He became a Nazi voter, hoping that Hitler would undo the restrictions of the Versailles treaty and restore Germany to greatness.

But middle-class pastors like Niemöller soon grew troubled. Not only did the new regime attempt to place Protestant churches under state control, but it encouraged the growth of the “German Christian” movement, whose tens of thousands of members viewed Hitler as a messianic figure and sought to strip Jewish influences from Christianity. Though Bonhoeffer referred in 1934 to “dreamers and the naïve like Niemöller,” he was actually already working with such pastors to organize an opposition movement within the Evangelical Church.

In May 1934 Niemöller and other leaders of this opposition movement, which would become the Confessing Church, issued the Barmen Declaration, a statement against “German Christians” largely written by Swiss pastor Karl Barth: “We reject the false doctrine that, apart from this ministry, the Church could . . . give itself or allow itself to be given special leaders vested with ruling authority.”

But most bishops were conservatives who did not want to risk losing the privileges of churches long connected to the state. Wearied by political debates, many laypeople retreated from church involvement altogether. And even though their German Christian opponents derided Confessing Church leaders as “Jew-pastors,” those leaders actually did little to speak up for Jews who had not converted to Christianity (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). In 1935, the year that the Nuremberg Laws stripped Jews of citizenship, Niemöller preached that God had cursed his chosen people as a penalty for the Crucifixion.

“The purity of the blood”

On January 30, 1937, Adolf Hitler celebrated his fourth anniversary as German chancellor. Speaking before the Reichstag, Hitler professed “thankfulness to our Almighty God for having allowed me to bring this work to success,” but promised more struggles lay ahead: “Of all the tasks which we have to face, the noblest and most sacred for mankind is that each racial species must preserve the purity of the blood which God has given it.”

That same day Niemöller spoke in another part of Berlin. Now his message was different. He preached about the apostle Paul’s imprisonment and prayed for all non-Aryans who had been removed from their jobs during the Nazi revolution. Meanwhile Bonhoeffer was writing The Cost of Discipleship (which would be published later that year) and teaching at the Confessing Church’s underground seminary in Finkenwalde.

By year’s end the seminary was closed and Niemöller had been arrested under the Law for the Prevention of Treacherous Attacks on State and Party and the Law for the Maintenance of Respect for Party Uniforms. He served his time while awaiting trial, but the state hung onto him anyway: eventually he was transferred to the Dachau concentration camp.

Catholic resistance also flared up in 1937. The same day he gave his fourth anniversary speech, Hitler pinned gold Nazi membership badges on those members of his cabinet who had not yet joined the National Socialist party. But when he reached his devoutly Catholic postal and transport minister, Paul von Eltz-Rübenach, Eltz-Rübenach not only refused Hitler’s honor but loudly told the Führer to stop “oppressing the Church.” The infuriated Hitler stormed away, and Eltz-Rübenach resigned. Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels responded, “That’s the Catholics for you. They take orders from somewhere higher than the fatherland—the only truly saving church.”

Earlier that month anti-Nazi Catholic bishops led by Michael von Faulhaber and Clemens von Galen had traveled to Rome. Together with the Vatican’s chief diplomat, Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII), they convinced Pope Pius XI to issue a German-language encyclical—a departure from the usual Latin—to condemn the abuses of a regime that had promised in 1933 to leave Catholic institutions alone in return for the church staying out of political affairs.

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Mit brennender Sorge (With Burning Concern) was eventually smuggled into the Third Reich and read aloud from Catholic pulpits across Germany on Palm Sunday:

Thousands of voices ring into your ears a Gospel which has not been revealed by the Father of Heaven. Thousands of pens are wielded in the service of a Christianity, which is not of Christ. … He who sings hymns of loyalty to this terrestrial country should not . . . become unfaithful to God and His Church, or a deserter and traitor to His heavenly country.

Catholics also worried about state interference with confessional schools. For example in November 1935, the education minister of Oldenburg had promoted the anti-Christian literature of Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg and tried to ban the public display of crucifixes. In response one priest told 3,000 Catholic veterans gathered for Remembrance Day that he would die for the cause, if necessary.

That Nazi official backed down; Hitler remained leery of alienating the faithful. But in 1937 the gloves came off. Hitler ordered all copies of Pius’s encyclical seized, and Goebbels spread allegations that the church harbored clergy who sexually abused boys and mentally ill men. Even in Germany’s most Catholic region, Bavaria, enrollment in confessional schools plummeted, from 84 percent of Bavarian children in 1934 to 5 percent four years later.

SS leader Heinrich Himmler and his violently anticlerical deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, secured restrictions on Catholic pilgrimages and bans on Catholic marriage and parenthood classes. Catholic youth groups and monasteries closed. As many as one in three priests faced state discipline or imprisonment.

But even so the “Red Threat,” as Communism was called, loomed larger for Catholics: five days after issuing his German encyclical, Pius XI addressed an even more strongly worded one against Communism, “which aims at upsetting the social order and at undermining the very foundations of Christian civilization.”

Moreover, Mit brennender Sorge criticized Nazi racism without explicitly defending the Jewish people. Neither Catholic nor Protestant leaders spoke out effectively in the wake of Kristallnacht, the November 1938 pogrom that moved Europe closer to the exterminationist violence of the Final Solution. (Bishop Martin Sasse of the official German church instead exulted that “on Luther’s birthday, the synagogues are burning in Germany.”)

When Germany finally went to war in September 1939, Protestants and Catholics alike filled the ranks of the German military, wearing belt buckles that paired the broken cross of the swastika with the traditional German military claim, “God with us.”

Hiding places

As the Holocaust began under the cover of war, some Christians did step up resistance. Thanks to the Lutheran Church in German-occupied Denmark and the Orthodox in German-allied Bulgaria, the vast majority of Jews in those countries survived. Reformed Protestants like French pastor André Trocmé and Dutch watchmaker Corrie ten Boom risked their lives to hide Jewish refugees (see “There is no pit so deep God’s love is not deeper still,” pp. 40–43).

Many scholars still criticize Pius XII for failing to speak out more publicly against Nazi atrocities, but his defenders have pointed out the role of Catholic officials in helping to rescue Italian Jews (see “A war story: Italian Catholics and a fascist Europe,” pp. 37–39).

In Germany itself, too, some refused to stay silent in the face of radical evil. Clemens von Galen preached against the T4 euthanasia program, which ultimately extinguished the lives of 200,000 mentally and physically disabled children and adults. Christian faith inspired Sophie and Hans Scholl and others of the “White Rose,” students whose nonviolent resistance through pamphlets and graffiti led to their arrest and execution in February 1943. A third of the country’s 30,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses were imprisoned for their refusal to serve in the military or give the Nazi salute; as many as a thousand died in the camps.

But even when those as courageous as von Galen protested treatment of Jews from their pulpits, they saved their sharpest words to critique new state sanctions limiting Christian practice. And as the details of the Final Solution became known, church leaders largely retreated in fear and complained only in private.

In the end most Christian laity and clergy were bystanders, if not willing perpetrators. Holocaust scholar Victoria Barnett writes,

The genocide of the European Jews would have been impossible without the active participation of bystanders to carry it out and the failure of numerous parties to intervene to stop it. … Moreover, the genocide was preceded by years of intensifying anti-Jewish persecution, which much of Europe’s non-Jewish population either witnessed or participated in.

“There is guilt between us”

On April 9, 1945, to the sounds of nearing Allied artillery, seven anti-Nazi resisters were hanged at the Flössenburg concentration camp. One was Dietrich Bonhoeffer, whose efforts to rescue Jews had resulted in his arrest in 1943. In 1944 the Gestapo discovered that he was also part of a plot to assassinate Hitler. The camp doctor who watched the brutal execution said of Bonhoeffer, “I have hardly ever seen a man die so entirely submissive to the will of God.”

Unlike hundreds of other priests and pastors held at Dachau, Martin Niemöller survived imprisonment. While he exerted significant moral authority in post-Nazi Germany, Niemoller knew that he and the Christians had largely failed the test when faced with the crimes of the Third Reich. In his 1946 memoir, he confessed that he felt compelled to tell any Jew he met, “Dear Friend, I stand in front of you, but we can not get together, for there is guilt between us. I have sinned and my people [have] sinned against thy people and against thyself.” CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Christopher Gehrz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Christopher Gehrz is professor of history at Bethel University, editor of The Pietist Vision of Christian Higher Education, and co-author of The Pietist Option, and he blogs at The Pietist Schoolman and The Anxious Bench.Next articles

Dietrich Bonhoeffer sees the handwriting on the wall

Grace is costly because it was costly to God

Dietrich BonhoefferA war story: Italian Catholics and a Fascist Europe

Mussolini, two popes, and hundreds of false papers

Matt ForsterA war story: “There is no pit so deep God’s love is not deeper still“

Corrie ten Boom worked to save Jews; Edith Stein was martyred because she was one

Kaylena RadcliffSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate