Spreading light in a dark world

IN 1944, the same year Allied forces stormed the beaches of occupied Europe, the congregation of Boston’s historic Park Street Church began giving up some meals during Lent. They sent the money they would have spent on food to the War Relief Fund, an initiative created by the newly formed (1942) National Association of Evangelicals (NAE). They were not alone in their desire to alleviate the suffering in war-torn Europe. Now known as World Relief, this fund was just one of many new Christian service organizations spurred into being by the world wars.

The call of the refugees

In World War I modern industrial war disrupted trade, destroyed farms, and decimated populations of young men, all while Europe experienced harsh winters and crop failures. Throngs of people became refugees, including women and orphaned children. Prisoners of war occupied temporary camps filled with disease and lacking adequate food and basic services.

In Belgium the 1914 German invasion displaced thousands. The following year the Ottoman government systematically brutalized the Armenian population in what most experts now consider genocide. Then in 1921–1922, the Russian people suffered through one of the worst famines in history, a suffering made worse by the Russian government’s policies and resulting in approximately 5,000,000 deaths.

Protestant missionaries helped to raise awareness about these atrocities, sometimes collaborating with nonreligious humanitarian groups such as the Near East Foundation (founded in New York in 1915). Others worked with international organizations such as the League of Nations. Karen Jeppe, a Danish missionary who founded a farming colony near Aleppo, Syria, for Armenian survivors, wrote when she took on the task,

How would I supply for all these people? It is quite certain that if I have got them out of the harems, then I will also be responsible for what becomes of them. And who will finance this huge enterprise? I have very little trust in the whole affair. But it may be a vocation. Well, then I must apply myself to it, however much I resist.

Later, when the League questioned her about the work, she made the shortest speech in its history: “Yes, it is only a little light, but the night is so dark.”

“They have never tasted milk”

Some of the earliest Christians to respond to these tragedies were the “peace churches,” including the Society of Friends (Quakers) and the Mennonites. The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), formed in 1917, provided nonviolent opportunities for conscientious objectors to serve their countries, but also became the primary facilitator for all kinds of humanitarian efforts.

Friends made up a small army of ambulance drivers and medical personnel. They cared for orphans, refugees, and prisoners of war and were among the most active in providing relief during the Russian famine. In Austria Friends helped supply milk through a program called “Cows for Vienna.”

The New York Times reported on the “sufferings of the little children” in Austria—where many children, it said, “have never tasted milk.” The AFSC bought cows in Holland or Switzerland and gave them to farmers in Austria, who donated a portion of the milk to Quaker Infant Welfare Centers. Friends considered this a natural embodiment of their religious commitments to peacemaking and social justice. So did American Mennonites, who established the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) in 1920.

Even prior to World War I, the American branch of the YMCA served among military personnel in America and abroad. Although the YMCA and YWCA mostly provided services and aid to American servicemen and women, their work extended to enemy prisoners of war held in miserable conditions in Europe. They partnered with other humanitarian agencies, such as the Rockefeller Foundation.

Prominent Methodist and YMCA leader John Mott wrote directly to oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, pressing for resources to help the 2,000,000 POWs on both sides “in grave danger of physical, mental and moral deterioration unless something is done to occupy their minds, and so far as possible, their bodies.”

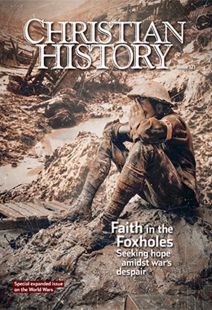

Order Christian History #121: Faith in the Foxholes in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

In World War II when Hitler’s Final Solution became public, the plight of Jews gave Christians new reasons for activism. Though Christians often were criticized for not doing more, Catholics in Europe did take measures to rescue Jews, and American Protestants supported Roosevelt’s new War Refugee Board. In fact most of the relief agencies that continue to work globally with suffering people today had their beginnings in the years surrounding World War II: the Methodist Committee for Overseas Relief (1940), Episcopal Relief and Development (1940), Catholic Relief Services (1943), World Relief (1944), Lutheran World Relief (1945), Church World Service (1946), World Vision (1950), and Compassion International (1952).

Haunting Hoover’s mind

The Christian desire to alleviate suffering was often complicated by prejudice or political realities. Herbert Hoover’s Quaker heritage influenced his leadership in the government’s war relief program; he remarked early in World War I as he led the Commission for Relief in Belgium, “Were it not for the haunting picture in one’s mind of all the long line of people standing outside the relief stations in Belgium, I would have thrown over the position long since.” But it also promoted American political interests.

Some Americans struggled to overcome antipathy toward the Russians, and Christian missionaries among the suffering Armenians were tempted to see their efforts as a means of civilizing the inferior “Turk.” Prejudice sometimes marred even efforts to help Holocaust survivors. Jeannine Burk, a Belgian Jew who was hidden with a woman in Belgium when she was a child, wrote later, “I lived inside this house for two years. Occasionally, I was allowed to go out in the back yard. I was never allowed to go out front. I was never mistreated. Ever! But I was never loved. I lost a great part of my childhood simply because I was a Jew.”

Another survivor, Shep Zitler, who came to the United States as an adult, wrote of encountering a different kind of prejudice: “I remember the first time I came into a bus in New Orleans. I sat in the back of the bus, where I like to sit. A few people looked at me. That was where the blacks were supposed to sit. I found out about segregation, but I did not understand.”

Save the world

Among American evangelicals, the rise of new organizations in the wake of World War II corresponded with a more expansive mindset. The founders of Christianity Today and the NAE sought to foster a broader and less separatist posture with a stronger commitment to social causes and global justice. In saving their grocery money, Boston’s Park Street parishioners followed the lead of their pastor Harold J. Ockenga, one of the NEA’s “new evangelical” leaders.

Overall, wartime relief among Christians had lasting, positive effects, sparking a willingness in denominations to work together and helping to facilitate a new ecumenical spirit. It also spurred cooperation between Christian and secular groups toward humanitarian ends, like Pope Benedict XV’s official support in 1920 of Save the Children Fund, the first time a non-Catholic charity received such support from the Vatican.

Though Christians had been known for centuries for their care for the poor and destitute, earlier grassroots efforts were not as highly structured or wide ranging. The world wars jumpstarted the many professional relief efforts Christians now take for granted.

Of the many Christian traditions embracing organized relief work, the Quakers alone were recognized on a global scale. Nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize five times, they finally received one in 1947. When the chairman of the Nobel Committee, Gunnar Jahn, presented the award, his description fit any number of Christians who sacrificed out of compassion for the suffering individuals of war-torn Europe:

The Quakers have shown us that it is possible to translate into action what lies deep in the hearts of many: compassion for others and the desire to help them—that rich expression of the sympathy between all men, regardless of nationality or race, which, transformed into deeds, must form the basis for lasting peace … the strength to be derived from faith in the victory of the spirit over force. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #121 Faith in the Foxholes. Read it in context here!

By Jared S. Burkholder

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #121 in 2017]

Jared S. Burkholder is associate professor of American and world history at Grace College and the editor of The Activist Impulse and Becoming Grace.Next articles

World Wars: Recommended resources

The landscape of resources about faith in the world wars is vast. Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors.

the editorsThe ecumenical dilemma

Protestants and Catholics share their experiences of the intersection between the two groups—from the Reformation until the present day

John W. O’Malley, S.J., Paul Rorem, Ernest Freeman, John Armstrong, Thomas A. BaimaEarly Church Heroines: Rulers, Prophets and Martyrs

Early church historians tell of the accomplishments of Christian women.

Ida Besancon SpencerSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate