New heaven, new earth

WHAT'S THE POINT? This question lay at the heart of classical Greek philosophy. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle emphasized the telos of life: its end, its objective, and thus its purpose. Spin the globe and we find Chinese philosophers Lao-zi, Zhuang-zi, Kong-zi (whom we know as “Confucius”), and Meng-zi asking a similar question: what is the best possible outcome of human life?

Great thinkers throughout all of history have examined human life in light of its end goal. But ancient Hebrew prophets and early Christian teachers agreed on something further: that we understand the present and the past best in the light of a clearly understood future. The Bible ends, after all, with pictures of The End, drawing to a fitting climax the narrative of the great story of creation, fall, and redemption while serving simultaneously as the overture to the splendid age to come.

The “eternal life” promised by Jesus in John’s Gospel is, more accurately, the life of that “age to come.” But the Bible as a whole argues that it is not only the life that is coming; it is the life Christians are to experience now, a new life of power, goodness, and joy. What, then, does the full realization of this life of power, goodness, and joy look like? What is the next life that shines backward, as it were, into this one?

Will we go up to heaven?

Despite the testimony of Isaiah 64:4 that “eye hath not seen” what God has prepared, the Bible ultimately doesn’t settle for keeping the afterlife a mystery. Moses stood before Israel and set before them life and death, blessing and cursing, a land flowing with milk and honey contrasted with a desert of wandering and waste (Deut. 30). God gave Ezekiel and then John dramatic visions to relay to God’s people about what lay before them: a fabulous garden city of prosperity, security, pleasure, community, and worship—or a nightmare of want, pain, desolation, sorrow, and darkness.

Both biblical Hebrew and Greek use “the heavens” to point up to the sky, to the starry reaches above that, and to the very abode of God. And many modern biblical scholars and theologians believe that humans are not going “up” there.

Instead, the argument is, Old Testament visions look toward a re-formed Israel enjoying shalom (peace) in the Promised Land and celebrating God in the refurbished, expanded, and glorified city of Jerusalem. Likewise, the New Testament gestures prophetically toward a renewed heaven and earth (parallel with Gen. 1:1) in which the New Jerusalem descends from heaven to earth as the focus of God’s redeemed creation

(Rev. 21–22).

So we will not go to heaven, but heaven will come to us. By this account, heaven is the abode of God, and humans cannot live there. Heaven represents God’s unapproachable transcendence. Rather, in a new heaven and a new earth we will enjoy the unspeakable blessing of communion with God who descends to inhabit the city he makes for humanity.

The Bible in fact paints a beautiful picture of God drawing nearer and nearer to humans: in the Old Testament tabernacle and temple, in the New Testament Incarnation of God’s Son where God dwells in the “tabernacle” of human flesh, and finally in the astounding indwelling of Pentecost, making Christians themselves “temples of the Holy Spirit.” In the New Jerusalem to come, there is no tabernacle or temple at all, for “its temple is the Lord God the Almighty and the Lamb” (Rev. 21:22).

Looking at the world to come

The idea of “going up to heaven” exerted great power over subsequent Christian images of heaven. But in many ways it recast the biblical theme in terms of a Greek worldview, which preferred to speak of spiritual over material, vertical over horizontal, and space (“up”) over time (“forward”).

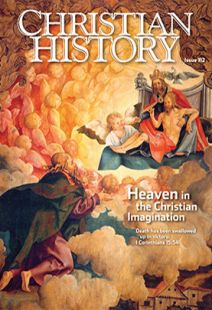

In the poetic, dramatic, and graphic arts of the Christian tradition (see “A garden, a city, a home, and a judgment,” pp. 16–21), humanity’s final destiny has been portrayed as a place where the highest aspirations of the human heart will be realized. This often focuses on the loveliness of God and the experience of what is called the “beatific vision.” Since God is the most beautiful of all, heaven has been said to consist simply in the eternal contemplation and enjoyment of God.

This view of the ultimate destiny of the blessed stands literally at the center of Dante’s vision of paradise, where the saints sit in ordered circles around the Trinity. They gaze at God forever in their appropriate ranks—not unlike the Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena, where no one pays attention to the other fans but only to the activity in the middle; in this case, God himself.

Luther and Calvin shared in this medieval outlook, and that focus upon heaven as eternal contemplation of the loveliness of God shows up in later spiritual writers as diverse as Madame Guyon, Richard Baxter, John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and John Henry Newman. Collages of images drawn from the kaleidoscope of John’s Revelation dominate such writings: angelic and saintly choirs in close-packed ranks singing and shouting praise to God enthroned on high.

Though the reformers and their successors primarily described heaven in spiritual terms, the biblical imagery of a new heaven and a new earth sometimes had a place in their rhetoric. Isaac Watts broke with this inherited tradition of heaven as perpetual contemplation most famously in “Joy to the World,” which was written to proclaim Christ’s Second Coming:

No more let sins and sorrows grow,

Nor thorns infest the ground;

He comes to make His blessings flow

Far as the curse is found. (See p. 38.)

The new earth as described by these writers is a safe and orderly place, versus the threatening chaos of most societies in history. It is a clean and beautiful place, versus earthly squalor. It is a place of abundant food, splendid clothes, delightful music, and running water—all luxuries denied so many on earth. And it is even fragrant. Modern middle-class North Americans, rarely troubled by anything worse than excessive perfume, can read in Christian tradition many accounts of sweet smells in the world to come and remember how overwhelmingly not sweet-smelling so much of world history has been.

Somewhere up there

But biblical language about a new heaven and a new earth sat uneasily together with the focus on the beatific vision for many Reformation theologians. Luther maintained the faithful would merely visit the new earth, while Calvin held that they would find contemplating the surpassing greatness of God far more interesting than tending the new earth.

In fact, church creedal statements since the Reformation have not devoted a lot of space to heaven. Conceived during a period of persecution, the brief Anabaptist Schleitheim Confession of 1527 spoke to the urgencies of the day and didn’t even mention the next life. And in 1530 the Lutheran Augsburg Confession simply offered “eternal life and everlasting joys” in the midst of more pressing matters such as condemning Pelagians, Donatists, and the aforementioned Anabaptists.

The Heidelberg Catechism (1563) promised to Reformed Christians that Jesus Christ, “our Head, will also take us, his members, up to himself” where they will “hereafter reign with him eternally over all creatures.” Beyond those assurances believers could expect to “possess perfect blessedness, such as no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived—a blessedness in which to praise God forever” (an allusion to Is. 64:4).

The Catechism of the Council of Trent (1566) gave similar counsels to Roman Catholics: “As for the glory of the blessed, it shall be without measure, and the kinds of their solid joys and pleasures without number.” No article among the Anglican 39 Articles (1571) was devoted to the world to come; instead the Articles promised “everlasting felicity” in a clause dedicated to predestination and election.

This remarkable reticence showed up even in the generous expanses of the Westminster Confession (1646). Assuming an “immortal soul” (a point on which Christians have actually disagreed), the confession promised to the blessed in the so-called intermediate state between death and the Last Judgment: “The bodies of men, after death, return to dust, and see corruption: but their souls, which neither die nor sleep, having an immortal subsistence, immediately return to God who gave them: the souls of the righteous, being then made perfect in holiness, are received into the highest heavens, where they behold the face of God, in light and glory, waiting for the full redemption of their bodies.” After the judgment, “the righteous [shall] go into everlasting life, and receive that fullness of joy and refreshing, which shall come from the presence of the Lord.”

World abandoned or transformed

The more recent (1992) Catholic Catechism goes into much greater detail: “By his death and Resurrection, Jesus Christ has ‘opened’ heaven to us. The life of the blessed consists in the full and perfect possession of the fruits of the redemption accomplished by Christ. . . . Heaven is the blessed community of all who are perfectly incorporated into Christ.” It sounds as if humans are, indeed, destined to go “up” to heaven.

But later the catechism promises a new heaven and a new earth right here: “The visible universe, then, is itself destined to be transformed, ‘so that the world itself, restored to its original state, facing no further obstacles, should be at the service of the just,’ sharing their glorification in the risen Jesus Christ” (quoting from Irenaeus, Against the Heretics). Later the writers claimed the world will be “once again, cleansed this time from the stain of sin, illuminated and transfigured, when Christ presents to his Father an eternal and universal kingdom.”

More recent evangelical statements preserve the terseness of their Protestant forebears on the subject. The landmark Lausanne Covenant (1974) only states, “Our Christian confidence is that God will perfect his kingdom, and we look forward with eager anticipation to that day, and to the new heaven and earth in which righteousness will dwell and God will reign forever.” The World Evangelical Alliance has for some time affirmed simply “the Resurrection of both the saved and the lost; they that are saved unto the resurrection of life, they that are lost unto the resurrection of damnation” (John 5:29).

Any work of theology, including confessions, creeds, and statements of faith, is aimed at solving a problem, answering a question, accomplishing a task in a particular context among a particular community. So none is ever comprehensive, let alone exhaustive, and theologians have rarely remarked on what to them seemed to be taken fairly for granted among the challenges of their day. Does it matter, then, that modern creedal documents generally say so little about the life to come?

Do other matters matter more?

The Bible itself might indicate that it does matter. Over and over again, prophets and pastors in both testaments referred to “what is to come” to warn and encourage God’s people. They set before the believing community a richly rendered view of the two alternative destinies—heaven and hell—for encouragement and exhortation.

If humans believe that “going up to heaven” is what awaits them, then most likely they will devote themselves to the mystical dimensions of the Christian religion—along with evangelizing to draw others, obediently and compassionately, into this glorious experience. They might engage in some immediate care for the needy too, but its focus will be preparing them for a solely spiritual destiny.

But among those who believe that the everlasting worship of God will take place on a renewed planet where humans will continue to fulfill the commandment of Genesis 1 and 2 to work the earth and make something of it, “earth-keeping” and “city-building” and “peace-making” emerge as crucial to the Christian vocation.

Thus, recently, some traditions have abandoned the focus on the beatific vision taken for granted by their founders. Work, rest, and play; education, politics, and art; worship, evangelism, and Christian fellowship—this “world-affirming” strain of Christian thought embraces all of these as integral not only to human existence today but also to human existence in the world to come.

In the end, our Christian brothers and sisters remind us that the Bible gives us good reason to forego the fatal goodies and the fatal extremes of the “way that seems right to a person” (Prov. 14:12). That reason is life everlasting in the company of God in the peaceable kingdom so powerfully depicted in Scripture. Without such a vision, the people stray off the narrow road and die (Prov. 29:18). With such a vision, however, we can set our minds on things above and ahead, where Christ is and where Christ will be, and keep on as we should. CH

By John Stackhouse

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #112 in 2014]

John Stackhouse holds the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Chair of Theology and Culture at Regent College, Vancouver, Canada.Next articles

Another stop on the glory train?

Christians have wrestled for years—sometimes with each other—over whether there might be a “precursor” to heaven

Jerry L. WallsTill we reach the golden strand

Pilgrim’s Progress gave many generations of Christians a way to understand their journey to heaven

Edwin Woodruff TaitHeaven Lost and Heaven Found

Ever since the Enlightenment, some thinkers have tried to “think away” heaven, but it is still going strong

Jeffrey Burton RussellSinging our way home

Famous Christian hymns about heaven—and the hope for heaven—from the church fathers to our own day

The Editors and hymn writers through the agesSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate