Heaven, Did you know?

The river came in a dream

Pastor, hymn writer, and composer Robert Lowry gave us the famous nineteenth-century hymn about heaven, “Shall we gather at the river?” In his own words: “One afternoon in July, 1864 . . . the weather was oppressively hot, and I was lying on a lounge in a state of physical exhaustion. . . . My imagination began to take itself wings. . . . The imagery of the apocalypse took the form of a tableau. Brightest of all were the throne, the heavenly river, and the gathering of the saints. . . . I began to wonder why the hymn writers had said so much about the ‘river of death’ and so little about the ‘pure water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and the Lamb.’ As I mused, the words began to construct themselves. They came first as a question of Christian inquiry, ‘Shall we gather?’ Then they broke in chorus, ‘Yes, we’ll gather.’ On this question and answer the hymn developed itself.”

Do dogs go to heaven?

Surprisingly, John Wesley thought so, as he expressed in his sermon “The General Deliverance,” based on Romans 8:22 (“We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now”). Wesley talked about the original happy state of animals in paradise, the way the Fall cut off God’s plan to bless animals as well as humans, and God’s final desire to see not only humans but animals have every tear wiped from their eyes (Rev. 21:4): “They [animals] ‘shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption, into glorious liberty,’—even a measure, according as they are capable,—of ‘the liberty of the children of God.’”

Who else will we see there?

As our History of Hell guide describes, the debate about whether God will save everyone (and what will happen to the rest if he doesn’t—annihilation or eternal torment) has raged for centuries. Many Christian thinkers have argued the traditional view that at least some people will reject God and never make it to heaven. But some have maintained universalism, the idea that everyone will eventually be reconciled to God, often after a long period of suffering and purgation.

Christians explicitly teaching a form of universalism include Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Hans Denck, William Law, and George MacDonald. Some others—including Maximus the Confessor, Julian of Norwich, and Karl Barth—implied such a view even if they did not directly state it.

Similarly, the idea that God predestines some to salvation has spurred debate from Augustine’s day to ours—debate which intensified after the Protestant Reformation. Today Calvinists are known for insisting that only some of us are among the elect who will persevere in faith until the end. Other Christian traditions either make this idea less central or reject it completely.

Dante's vision

What is one of the most imaginative visions of heaven and hell in Western culture? Dante’s fourteenth-century Divine Comedy (covered in CH 70, Dante’s Guide to Heaven and Hell). Dante’s three-part poem, one of the first serious literary works to be written in the vernacular rather than in Latin, sold like hotcakes for centuries. (No doubt many people were eager to see who had ended up in hell—like Pope Boniface VIII—and in heaven—where Dante placed not only saints of the church but also Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII.) The book was hand-copied over 600 times in his own century, spawned 12 contemporary commentaries, and eventually became one of the first books to be set in movable type. Interest in the tale waned for a while, but revived in the nineteenth century.

Further up and further in

C. S. Lewis profoundly impacted modern Christian images of heaven in his novels The Great Divorce (1945) and The Last Battle (1956). The Great Divorce tells about bus passengers on an excursion from a “grim city” to a beautiful heavenly landscape. Very few passengers choose to remain there when they discover that doing so means submitting to the lordship of Christ.

The Last Battle pictures the closing days of Lewis’s imaginary Narnian world. After a dramatic judgment scene, the heroes journey ”further up and further in” to Narnia’s green and beautiful new heaven and new earth: “The things that began to happen after that were so great and beautiful that I cannot write them. . . . Now at last they were beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on for ever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.” Lewis also described the medieval view of heaven in The Discarded Image (1964), and his friend Charles Williams penned a novel in which the afterlife looks like the city of London—All Hallows’ Eve (1945).

Building the New Jerusalem

Many of us have sung “Christ is made the sure foundation / Christ the head and cornerstone” as we dedicate new churches. But did you know these lines are part of a hymn about the heavenly Jerusalem? Dating from the seventh century, John of Damascus’s famous lyric begins by describing the heavenly Jerusalem descending to earth as the bride of Christ decked with jewels. Christians through the years have seized on Revelation’s imagery to describe heaven as a beautiful jeweled city, inhabited by the redeemed who unendingly sing God’s praises.

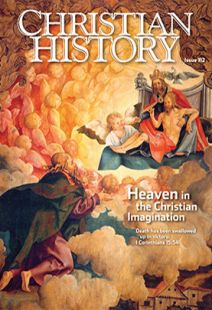

Cover

On our cover: While the apostle Paul is often depicted standing next to Christ and Peter in heaven, images of his entry into heaven are relatively rare. This painting by Hans Suess von Kulmbach, who studied under Albrecht Dürer, imagines the apostle approaching the enthroned Trinity after his death. Perhaps the artist had Paul’s description of a vision of the third heaven (2 Cor. 12) in mind. CH

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #112 in 2014]

Next articles

Editor's note: Heaven

Christians have tried to express a beauty that is ultimately inexpressible

Jennifer Woodruff TaitHeaven’s fire department?

Modern American attitudes about heaven range from comforting to baffling

Rebecca Price JanneyGetting ready for heaven

Hell may be the best God can do for those who don't care for heavenly things

Gary Black Jr.“God’s love that moves the sun and other stars”

Christians in the early and medieval church gave us patterns that still govern how we think of heaven

Jeffrey Burton RussellSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate