“Lord, bend us”

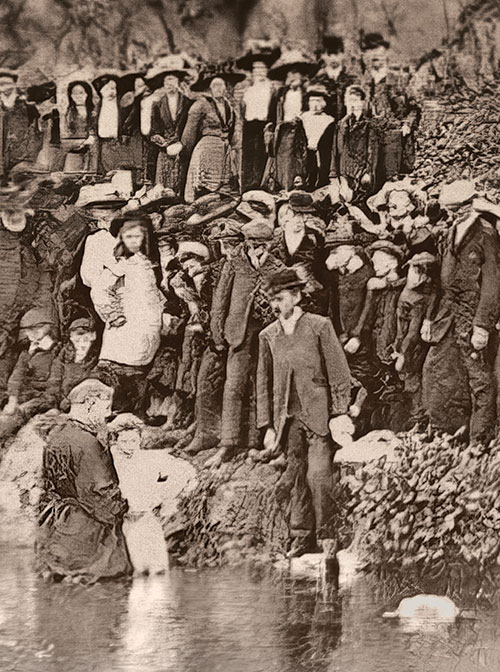

[Baptism in the River Gwaun, c. 1905—Fishguard and Goodwick local history]

The Welsh revival of 1904–1905 stands out as one of the most important spiritual awakenings in modern times. Its origins were mainly indigenous, in a long tradition of Welsh revivals, but its influence was international.

Never before in church history had there been such a great revival influence flowing from one country into so many others in such a short time. There were many historical connections between Wales and other movements, such as India 1905–1907, Los Angeles 1906, and Korea 1906–1907, to name only a few.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Welsh society was in a period of great change and turmoil. On one side it nearly exploded with energy and optimism. People were fascinated by technological progress and amazing inventions (like the sewing machine) and benefiting from recent chemical discoveries and the minor products of new industries, like cheap coal and newspapers.

But besides the optimism was great economic, political, and social unrest that could not fail to affect the people’s Christian faith. Since 1850 industry had begun to change the face of the country. As aggressive capitalism of heavy industry expanded, coal mining employed more people than any other industry, and Cardiff became the biggest coal export harbor in the world. But the quick and unstructured growth of the industrial cities created many social, spiritual, and moral problems for the church to grapple with.

Humble Beginnings

On the second Sunday in February 1904, in the town of New Quay, a girl named Florrie Evans (1884–1967) gave a very simple testimony in a meeting of young people: “I am not able to say very much today but I love the Lord Jesus with all my heart—he died for me.” The gathering was said to have become very quiet and then excited in sensing the awful and overwhelming presence of God.

These unpretentious words became a spark igniting a widespread revival as young people fanned the flame in neighboring congregations. At the heart of these events, pastor Seth Joshua (1858–1925) noted in his diary:

The revival is breaking out here in greater power. The spirit of prayer and of testimony is falling in a marvelous manner. The young are receiving the greatest measure of blessing. The revival goes on. . . . I have closed the service several times and yet it would break out again quite beyond the control of human power. . . . Group after group came out to the front seeking the full assurance of faith. What was wonderful to me was the fact that every person engaged in prayer, without one exception.

Bent on revival

The best-known figure of the revival, raised in a Welsh Calvinist Methodist family in Loughor in the south, had an intensive spiritual life even as a boy. Evan Roberts (1878–1951) wrote later: “I could sit up all night to read or talk about revivals.” In 1903, after working in a coal mine and as a blacksmith, he entered a preparatory school for the ministry at Newcastle Emlyn at the

age of 25.

During this time Roberts attended a meeting in Blaenannerch on the west coast of Wales, where preacher Seth Joshua prayed, “Lord, bend us.” Later Evan Roberts experienced a powerful filling with the Holy Spirit and the decisive call for his future life:

I felt a living power pervading my bosom . . . the tears flowed in streams. . . . I cried out “Bend me! Bend me! Bend us!” . . . I was filled with compassion for those who must bend at the judgment, and I wept. . . . I felt ablaze with a desire to go through the length and breadth of Wales to tell of the Savior.

Soon afterward Roberts formed a team to preach the gospel everywhere in Wales. During the nights Roberts had visions, and one of them showed him preaching to his former classmates. This led him to conduct meetings in his hometown of Loughor.

After discouraging beginnings these meetings increased in numbers and intensity. People felt a mighty outpouring of the Spirit with much weeping, shouting, crying out, joy, and brokenness. News of the events spread like wildfire, as newspapers and Christian journals raised further expectations. A national newspaper, The Western Mail, reported:

Shopkeepers are closing earlier in order to get a place in the chapel, and tin and steel workers throng the place in their working clothes. The only theme of conversation among all classes and sects is “Evan Roberts.” Even the taprooms of the public-houses are given over to discussion on the origin of the powers possessed by him.

Evan Roberts and beyond

Roberts’s revival meetings started with his team of young women singing and giving testimony. He sometimes came late and remained hours in prayer, often in tears on his knees or lying prostrate on the floor. He never gave a prepared sermon, but claimed to be guided by the Spirit alone. Roberts announced four conditions for gaining the full blessing of the Holy Spirit: 1) confessing openly and fully to God any sin not confessed to him before; 2) doing away with anything doubtful in ourselves; 3) giving prompt obedience to the influences of the Holy Spirit in the heart; and 4) confessing Christ openly and publicly before the world.

Sometimes he did not preach at all, but the meetings seemed to guide themselves. They began long before he arrived and lasted late into the night, people often losing their sense of time. The numbers increased, with often thousands, even tens of thousands, waiting for him.

The revival had strong support—even bishops of the Anglican Church declared publicly that it was a genuine work of God.

At the end of March 1905, Roberts started his fourth—and most controversial—campaign in Liverpool, England, which had a large Welsh population. Even more than usual, he interrupted singing and prayers, stating that there were obstacles and that the “place must be cleansed,” for example, because some were refusing to forgive. His announcement of “a direct message from God” that the Welsh Free Church (which sponsored this campaign) “is not founded on the Rock” created great uproar. In the newspaper he was attacked on the grounds that his public work was a “sham.” Even a sympathetic biographer wrote that “in the heat of the moment Evan Roberts was claiming powers for himself that no individual can ever have.”

After this campaign Roberts underwent a medical examination that found him mentally sound but overworked. About a year later, he retired from the public eye, apparently suffering from what we would call burnout.

Church leaders continued to hold campaigns, emphasizing that this was not the “Evan Roberts Revival.” Some of these meetings bore the influence of the Roberts campaigns, but some were completely independent. There were also processions through the streets, often including children, with Christians spreading the gospel. In many places Nonconformists and Anglicans met together, expressing

Christian unity.

Changing society

The immediate social effects of this spiritual movement were obvious to everybody, and some became proverbial. In many places in Wales for some months, magistrates found themselves presented with white gloves as a sign that there were no criminal cases to be treated. The usual hundreds of cases of drunkenness in the populous centers were significantly reduced. In one place the policemen were so underemployed that they had nothing better to do than to form a church choir. The effect on the drinking habits of many was striking. Many public-houses, almost immediately, became practically empty. Workers brought their wages home to their poor families or gave part of them for charitable purposes instead of wasting them. Many homes underwent a complete transformation since the parents were brought to a better life through

the revival.

In the coal pits, miners gathered to pray and praise God before they began their hard work. The revival resulted in lots of debts being repaid and the reconciliation of bitter enemies. Young people in different areas visited the poor and sick, providing Bibles, food, and clothing for the needy. More long-lasting were the institutions formed by the revival, like Rescue Homes for homeless men and for women who had once earned their money by prostitution.

Estimates of the total number of converts vary between 80,000 and 162,000, and the increase of membership in all churches was substantial. As a result of the revival, many men and women felt the call to go out into the world by faith as witnesses, some on their own subjective call, others sent by existing or newly formed missionary societies. On the institutional level, children of the revival founded new independent churches, opened three Bible schools, and started an evangelical magazine, among other

social enterprises.

One writer referred to the “huge phalanx of church leaders” that emerged. In a way the revival gave the Welsh church the leadership it needed to face the challenges of the following decades: World War I and the Great Depression. Never before did so many women get involved in the public work of the churches—and this too turned out to be providential in the coming years, as many Welsh congregations had to rely on women more than men.

And we must not underestimate the lasting effects of the revival on individuals, even after the emotional heat dissipated. As W. T. Stead observed,

The fruits of revivals are among the most permanent things in history . . . while some undoubtedly fall away, and very few indeed ever permanently retain the ecstasy and the vision of the moment of their conversion, the majority of converts made in times of revival remain steadfast. CH

By Wolfgang Reinhardt

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #153 in 2024]

Wolfgang Reinhardt is an author, PhD theologian, and retired pastor. This article was adapted from “‘A Year of Rejoicing’: The Welsh Revival 1904–05 and Its International Challenges,” originally published in the April 2007 edition of Evangelical Review of Theology. It is reprinted with permission.Next articles

When the Spirit moves: CH153 Gallery

A diverse collection of revivalists from the 1800s and 1900s

Charlie SelfChristian History Timeline: The Spirit, the gospel, and prayer

Revival movements of the modern era

The editors